Thirteen years ago, during an unassuming Sunday football game on Fox, America suffered a mass hallucination–and it’s never woken up.

There was no explanation as to why a cyborg football player had suddenly appeared, hopping, stretching, and flexing across millions of TVs. He had no name, no origin story, and no fundamental logic justifying his existence. Yet viewers seemed to slowly adjust to this new reality like it had always been reality–that a robot doing jumping jacks next to an advertisement for a Ford F150 between plays was simply the natural course of things.

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]

“I just accepted he was there and somehow never questioned that he was there,” recalls Megan Greenwell, editor of Deadspin. Until one day she realized: “Wait a second, there’s a giant robot that dances across the screen on Fox Sports. What’s the deal with that?”

No one outside Fox knew where the robot–named Cleatus–came from, or which creative director summoned him from the depths of the network’s psyche. So, nine months ago, I reached out to Fox Sports–because I needed to know. I would blow this story wide open.

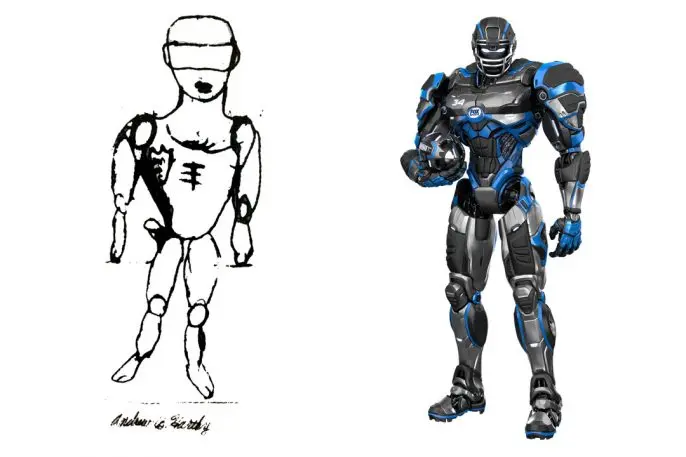

That email led to a cascade of interviews that reveled Cleatus’s origin story–a surprisingly funny and heartwarming tale that even features an unexpected celebrity cameo. If Cleatus seems like a mascot dreamed up by a 7-year-old, it’s because that is precisely what he is.

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]

The early days of Fox Sports

Fox always had a bit of a chip on its shoulder as a network. The youngest of the Big Four, it wasn’t NBC, ABC, or CBS. Since its launch in 1986, Fox had wanted an NFL broadcast contract, because it would bring a certain legitimacy to the channel as a broadcaster–not to mention, millions of households tuning into games every week, who might discover other programming they liked on Fox, too.

Fox founder Rupert Murdoch “snatched” CBS’s NFL rights away in a shocking deal for the 1994 season. Within just eight months, Murdoch brought in a man named David Hill to build Fox Sports from nothing. Hill was coming from the U.K., where he helped launch the Sky Television satellite service. He had a reputation for shaking things up and embracing gimmicks. In 2017, Hill was accused of sexual misconduct toward a fellow Fox employee in 1998 in a case that was settled out of court; he stayed at Fox with no clear repercussions.

Gary Hartley, now executive vice president of graphics at Fox Sports, likens Hill to P.T. Barnum, pointing out that, “he’s Australian, so he has no preconceived notion of what should or shouldn’t be part of a presentation of a sporting event.” In 1977, while producing cricket for Channel 9 in Australia, Hill introduced an animated duck named Daddles, who would appear when a batsman was dismissed without scoring. He cried and sulked back to the dugout.

“He got eviscerated in the press,” says Hartley. “They hated him for it.”

But Hill was focused on the future, not catering to purists. At the fledgling Fox Sports, he instituted a “no dead guys rule” to on-air MLB announcers, complaining that broadcasters spent all their time romanticizing early players like Babe Ruth rather than contemporary athletes.

When Hartley first joined Fox Sports in 1995, the graphics team had been experimenting, here and there, with a techie look, which included a few robots on some animations and brand packages. “The technology to do that in-house wasn’t there yet,” says Hartley. “They looked like shit to be honest.”

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]

When I asked Hartley if he had any idea why they started messing around with robots at all, he replies with an emphatic “no.”

“It was very much the antithesis of established sporting networks. It was L.A. We were on a movie lot. The average age of producers and production people was in their 20s,” says Hartley. “It was a fun place to work, and there wasn’t a lot of what I’d call ‘adult supervision.'”

“It was kind of a connection we had”

In 2005, CBS signed a major NFL deal, reigniting a feud with Fox.

“We were rebranding our package. And we knew a lot of guys working on the CBS package,” says Hartley. “And there was this weird competition we felt for some reason. I don’t know if CBS felt it, but we wanted to be top dog. And we had no money. Our budgets were low, and CBS was well-funded.”

Hartley and the team wanted to do something big, but exactly what that meant eluded them.

“I remember one day, my son, who was 7 or 8, had drawn me a picture of a hybrid robotic football-player-slash-cowboy. He was really sold: ‘You should do this! It would be so cool!’ says Hartley. Following a divorce, he had been traveling back and forth from L.A. to Chicago frequently to see his son, who lived 2,000 miles away. “It was in my desk, and I pulled it out one day, and it hit me. We should do this. But not create another robotic football player. Let’s create a character synonymous with the [Fox Sports] logo, that gives us the authority to interact [with the viewer].”

According to John Marshall, chief strategy officer at the global design firm Lippincott–which has developed branding for companies like Starbucks (and didn’t work on Cleatus)–the mascot was a good idea. After all, mascots, from Tony the Tiger to Mr. Clean, are well-worn tropes in advertising for a reason. To some extent, Marshall explains, the more random the character is, the better. After all, you want an ad to be memorable, not normal.

In the case of Fox coming in to claim football, a robotic mascot was actually a particularly good fit. “If you look at ESPN’s graphical filler between shots, it was built from almost mechanical pieces, copied by most sports networks,” says Marshall. “ESPN had a design language, and Fox turned it into this character.” For sports television, this was a first.

The team began sketching more formally what the robot would look like, and Hartley shared much of the early work with his son. “It was kind of a connection we had,” says Hartley. “He was part of the journey when we started developing it. It was kind of a cool thing.”

As 2D sketches transformed into 3D renders, Fox got to the stage where it was ready to animate the robot. They hired Blur Studios to handle the motion capture for a special effects sequence helmed by cofounder Tim Miller. Miller has since gone on to become a major director with his breakout film Deadpool–and directed the coming Terminator reboot.

Hartley remembers the first motion capture sessions clearly, as green-suited actors were asked to perform all sorts of things the robot might do. That included pointing, flexing, and taunting–the sort of machismo gesturing that was championed by a wave of mid-aughts dude-branding seen on contemporaries like SpikeTV.

A boastful, swole bro-bot is just the sort of over-indexing of masculinity that, seen through in a certain light, could have been interpreted as mocking Sunday football itself. “Immediately, we started getting reactions,” says Hartley. “This was pre-Twitter and all that stuff, but I remember . . . Louis Black, on an HBO show, the second week [the robot] is on the air, he cut to it, and was like, ‘What does this have to do with football?’ We were tweaking the purists, which I liked.”

Soon thereafter, with no one to say “no,”–Hill was the ultimate enabler–the creative team started to push the bounds of the robot’s behavior, treating it more like an ongoing gag than an austere touchdown-making machine. “I had what could be categorized as a ninth-grade sense of humor, so we had all this other stuff, so we really started getting into it.”

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]

They put the robot in costumes. Wrapped him in Christmas lights. Had him throw a snowball. Programmed him to mime. Even put him in a hula skirt. Some motion capture actor had to act out every iteration. The effect this ripped-yet-slapstick cyborg had on audiences was the equivalent of Arnold Schwarzenegger in Kindergarten Cop, or Dwayne Johnson in The Tooth Fairy. (Conan O’Brien would recognize the comedic opportunity, and mock the robot in a hilarious sketch by giving it a proctology exam in front of NFL footage.) It was an outright subversion of masculine tropes, which may have hit too close to home during weekly contests where 300-pound athletes slam into each other over and over again for a turf battle in a simulated war.

“I laughed my ass off, but I might have been the audience of one there,” says Hartley. Then in 2007, Fox threw an online naming contest for the robot. Fans selected “Cleatus,” a wonderfully wretched pun. He starred in a spot with another wonky brand icon, the Burger King King. The King zanily knocked Cleatus in the head with a football. You even hear a “DOIIIIING!!!”

Bad Cleatus

While he has never spoken, in 2012, Cleatus was given his own Twitter account–where he was meant to have a voice inspired by none other than Chuck Norris (or at least the internet’s ironic treatment of Chuck Norris).

Fox shut down the account in 2013, but, thank the heavens, didn’t delete it, which allows us to see just how poorly it was executed. Cleatus comes off like the worst sort of football fan, some guy who has been riding high since making the varsity team in 10th grade and punches you in the shoulder when you don’t laugh at his jokes.

Why do Field Goals feel like you came in second place? #Jac #Mia

— Cleatus (@CLEATUSonFOX) December 16, 2012

Now that the #Texans game is over #WadePhillips can get back to his job as caretaker at a Bed and Breakfast.

— Cleatus (@CLEATUSonFOX) December 30, 2012

It looks like Jay Cutler treats his wedding engagements like he does big games? He mails em in.

— Cleatus (@CLEATUSonFOX) February 8, 2013

"So wait, #MantiTeo did or didn't have a girlfriend?" – dude way out of the loop.

— Cleatus (@CLEATUSonFOX) February 22, 2013

Around the same time they were experimenting with Twitter, Fox Sports execs started imagining that Cleatus might not be just one robot, but a whole squad of robots, each of whom might represent a different sport. When I first hear this twist, I imagine hockey bots and badminton bots, stacking on top of one another like a Fox-branded Megazord.

Fox tried out a NASCAR bot called Speedus, a racing robot complete with his own giant wheel, for a year before abandoning the idea. When Fox signed the UFC to its FS1 network in 2013, it was looking for a way to legitimize a sport that John McCain had likened to “human cockfighting” with a TV-friendly brand. The answer was Beatus–Cleatus’s cousin. A Cleatus that would beat you up.

“In retrospect, we should have left it on the cutting-room floor,” laughs Robert Gottlieb, executive vice president of marketing at Fox Sports.

Cleatus was always absurd, but Beatus resembled a B-list manga superhero, with fierce red eyes and two big boxing gloves. He made multiple appearances on TV, in the studio and at events, not just as a graphic but as a live-action mascot–a person wearing a Beatus suit.

“Even though it gave [UFC] the Fox sheen, it didn’t give it the sport-legitimizing sheen we were looking for,” says Gottlieb. Who woulda thunk: Two bikini-clad models standing ringside punching an actor in a robot costume didn’t scream “legitimate sport”?

Oh sweet jesus, they're gonna make Chael interview the damn UFC FOX robot "Beatus" tonight…. @joerogan not pleased. pic.twitter.com/QEpQgCYQO6

— Word On The Street (@TheAntJimmyShow) April 30, 2014

Cleatus grows up

Hill was moving on to other projects when Eric Shanks–a Fox Sports alum–returned to the company to take over Fox Sports as president (now he’s CEO and executive producer of Fox Sports). Shanks was a Cleatus fan, and he was okay with the mascot ruffling some feathers among fans. But one of his first acts was to tighten the reins on the robot.

“Gary [Hartley] and I talked a lot about it, and the fact that Cleatus had become a catchall. If we wanted to put Cleatus in a hula skirt and dance, or if we wanted Cleatus to get beaten up, everything was fair game. And it just didn’t seem quite right,” says Shanks.

“That’s where we think Cleatus kind of hit rock bottom. We wanted to clean up his character, and set sort of a backstory and rules, for what Cleatus would and wouldn’t do.”

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]In other words, if Cleatus was going to be the brand of Fox Sports football, he needed some brand guidelines. During this era, Cleatus got what I mentally refer to as the Gears of War makeover: He was given Herculean shoulders and a Ken doll waistline that seem to defy the laws of physics, and eyes that appear more menacing than friendly.

“We wanted him to be a badass futuristic football player,” says Shanks. The team decided on his real-world size for the first time. He was no six footer–he was a Michael Bay Transformer who towered 12 to 17 feet in the air. Around the same time, Cleatus was given a presence in the real world, too, through augmented reality-style commercials.

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]

And the sales team inside Fox Sports began selling Cleatus as part of premium ad packaging.

Any lingering irony was stomped out as he evolved into the ultimate co-branding machine–a steadfast representation of football and Fox Sports that any sponsor would feel confident standing beside.

Cleatus has gone on to be part of dozens of movie integrations. He’s worn Beats headphones. He’s done cameos with Ford trucks.

[Image: courtesy Fox Sports]

“It’s like getting access to Fox Sports’ biggest star,” says Shanks. “It’s got to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars that Cleatus has been associated with.”

Cleatus has grown more important as a brand differentiator and revenue generator for Fox Sports as time has gone on. In an era when NFL football licensing fees have ballooned to billions of dollars for just a few dozen games, Cleatus has become essential to the brand strategy of Fox Sports. Yet for most of us, Cleatus’s appeal isn’t his techno-steroid physique or glowering scowl. It’s his sheer randomness–which began with his unexplained, inexplicable entrance into our lives. You simply couldn’t construct a stranger trope to be roasted on The Simpsons than Cleatus.

And it’s all ultimately because a designer missed his family, and wanted to build a character who would connect him to his son living 2,000 miles away.

“It’s funny to me that, for the most part, everybody just accepted it,” laughs Greenwell. “If you watch a decent amount of football, [you think], why wouldn’t the giant robot in pads be there? Of course he’s part of a football game! Even though . . . it genuinely makes no sense.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.