After poachers capture a baby chimp in Nigeria or the Ivory Coast–typically in a brutal process that involves killing the parents and other nearby adults so they can’t protect the infant–the animal often shows up on Instagram in posts targeting buyers overseas who are looking for a pet ape. A new facial recognition system for chimps may make it easier for conservation nonprofits and law enforcement to find those posts.

Right now, volunteers often comb through social networking sites by hand. “You just kind of have to click on one page and then the next page and then kind of muddle around aimlessly until you find something that looks suspicious,” says Alexandra Russo, founder of the new project, dubbed ChimpFace. “And I thought that seemed to be a really inefficient way to do it.”

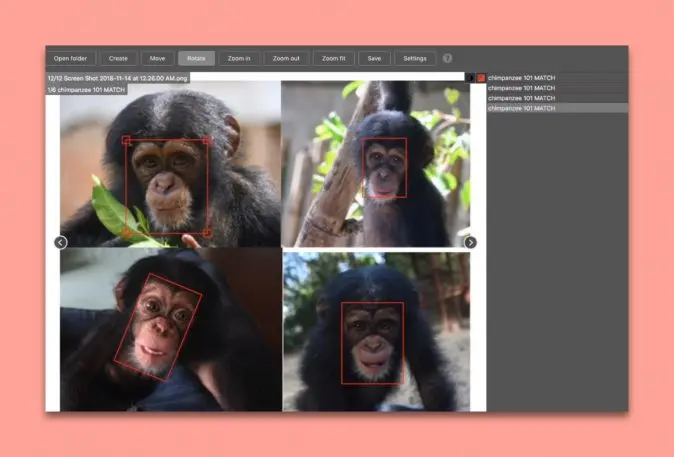

Russo partnered with Colin McCormick, a computer vision expert who consults with the nonprofit Conservation X Labs, to develop the algorithm. They gathered thousands of photos of chimps from conservation groups to help train the algorithm to accomplish the first step–identifying a chimpanzee in any picture. “That’s a relatively simple adaptation of a lot of standard object recognition algorithms out there,” says McCormick. As it’s fed more images, the tool will become more accurate.

The next step will be building an algorithm that can identify an individual chimp. “We can draw a lot from human facial recognition algorithms, which have been developed by Google, Facebook, and others,” he says. Those programs focus on features that are idiosyncratic in human faces; chimp faces, which are shaped differently, will have a different set of identifiers. “The way we’re thinking about this is to try to identify the specific set of structural features on the faces of chimpanzees that would be the equivalent fingerprint for individual identification, and that we think is sort of the heart of the challenge.” With full facial recognition in place, as a chimp moves from a smuggler’s cage to another country, the tool could identify that it’s the same animal, something that’s very difficult to do now.

The tool can help streamline the work of finding poachers. “We’re not imagining that the algorithm will be perfect,” McCormick says. “So what we’ll do is figure out a kind of a workflow process where the algorithm will flag likely posts and images that should be reviewed, and then we need a group of human experts to review [them].”

The prototype of the tool was a finalist in Conservation X Labs’ Con X Tech Prize in November 2018, and the team is now looking for a grant to run a year-long pilot. They hope to collaborate with law enforcement and other government officials and social media companies to develop the next iteration, and then continue to tweak the algorithm. It’s possible, for example, that the tool may find so many images that the programmers will need to incorporate keywords or geographic parameters to narrow the results.

It’s one attempt to tackle a massive problem. Every year, an estimated 3,000 great apes are lost from the wild because of the illegal wildlife trade–either because they end up in private homes or for-profit zoos or because they die in the process. Around two-thirds of these are chimpanzees, which are an endangered species. A year-long BBC investigation of the chimp trade suggests that 10 adult chimps are typically killed to obtain one infant. After the baby grows up–and can’t safely live in a house–it may be killed or spend the rest of its life in a cage.

Eventually, the tool could be adapted for other animals. (Other organizations and researchers are also working on similar tools, such as LemurFaceID, designed to help researchers track lemur populations in the wild over time.) “This project has the potential to really scale up and scale out, so if we can do it successfully with chimpanzees, we can in theory drag and drop other animals into the system, too,” says Russo. “Then we’re not only looking for traffickers that are selling chimpanzees, we’re able to study networks that are also dealing in other species that we can identify, so that will exponentially increase the number of transactions we can find.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.