When Mike Schroepfer joined Facebook in 2008 as VP of engineering, his most pressing responsibilities involved “trying to keep the wheels on the bus as it was barreling down the hill,” he says. “People forget how hard it was just to scale the site and keep it running and deal with all the technical challenges therein.”

After spending half a decade on that effort, Schroepfer was named Facebook’s CTO in March 2013. That was around the same time that he and CEO Mark Zuckerberg finally felt that the service was in good enough operational order to let them think seriously about its technological future. Among the conclusions that came out of that thinking was that AI was the next great frontier, and Facebook should take it seriously. The company formed a group called Facebook AI Research (FAIR) and hired computer-science legend Yann LeCun to run it—an appointment that Zuckerberg formally announced that December at NIPS (now NeuralIPS), the machine-learning field’s major confab.

At the time, however, Zuckerberg concluded that AI was at an inflection point that merited special attention (along with a few other areas such as VR and AR, which led to Facebook’s March 2014 deal to acquire Oculus). “You want things that are out of the theoretical realm and are already at or close to providing practical value, but are still in the bottom part of the S curve,” Schroepfer says. “Meaning there’s still a lot of known and tractable issues to solve. And AI is that in spades.”

FAIR has been working on solving these problems in ways that benefit Facebook’s namesake service, as well as Instagram and other products. Along the way, it’s shared its findings and open-sourced its work, giving its work importance beyond its application in Facebook products. For instance, PyTorch, FAIR’s open-source toolkit for creating machine-learning models, competes with Google’s popular TensorFlow, and recently gained support from Microsoft, which had previously focused on its own rival offerings.

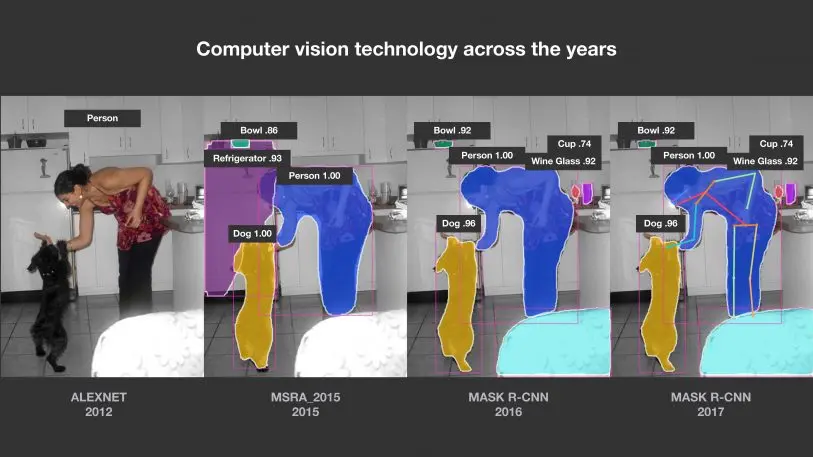

Today, “It’s no accident that we’re furthest ahead on computer vision, because that was the very first thing we worked on,” says Schroepfer. In 2013, a technological party trick such as using AI to identify photos of cats was still a bit of a mind-bender. Since then, Facebook and the rest of the industry have made major inroads: It’s possible for computers to not only pinpoint an array of objects with high accuracy and not just detect people, but also figure out what they’re doing. The company uses technology that originated in FAIR for such purposes as enhancing search, detecting various sorts of objectionable content, and automatically generating descriptions of photos for visually impaired users.

Some hard problems, however, remain hard—maybe even more so than they once seemed. In 2016, a flurry of excitement about bots—which were a key theme at Facebook’s F8 conference as well as Microsoft’s Build—led to giddy expectations that conversation might soon become a primary means of communicating with computers. But though computers can now beat expert humans at an array of tasks, from playing Go to transcribing audio, they can’t compete with a toddler when it comes to conversing.

“True dialogue systems—not things that can figure out what you’re asking for a timer or what the weather is, but can have a conversation with you and can remember what you said three utterances ago and refer to it and not sound like they have complete amnesia—are still pretty basic,” says Schroepfer. FAIR is still investing in conversational AI, but progress has been plodding, and he doesn’t expect any short-term breakthroughs.

Machines as moderators

At present, Facebook’s highest-profile challenges involve weighty matters such as fighting fake news, hate speech, and other forms of misuse of its platform that threaten not just the health of the company but society itself. In 2018, the company dramatically increased the amount of human intelligence it’s throwing at these problems by hiring thousands of additional content moderators. Though that underscores that AI isn’t a magical antidote to Facebook’s most serious problems, computers already do a vast amount of the gruntwork involved in keeping undesirable content off the network, ideally before it ever appears in the first place.

“If we didn’t have the muscle to deploy this sort of technology at the company at scale, and a bunch of the advancements we’ve made in the core technology, we would be in really deep trouble right now,” says Schroepfer. Apparently, he’s enough of an optimist to see the company’s current woes as less than a worst-case scenario.

He does admit to some frustration that the success Facebook has already had using AI to police the network isn’t better known. “The data is right in front of people’s faces,” he says, citing the company’s transparency report. Between July and September of this year, 96% of instances where Facebook took action on standards-violating content involved it taking down an item before any member had reported the item in question—a figure that Schroepfer says AI deserves virtually all of the credit for.

Related: Facebook’s fight against election tampering spans the company

Still, Schroepfer, like other Facebook executives, errs on the side of emphasizing that the company understands it has lots of work ahead when it comes to matters like protecting the integrity of elections. Rather than toiling in isolation, FAIR researchers are actively collaborating with other Facebook staffers on solutions to such issues. “That sort of interdisciplinary virtual team, combined with subject matter experts across the spectrum from AI to policy, is the way we’re going to get good at this,” he says.

Assessing content on Facebook services will always be central to FAIR’s work. But the organization continues to evolve: It’s lately been hiring robotics experts, a move LeCun has said is essential as many of the best brains in computer science dedicate themselves to the topic. FAIR engineers are even working with counterparts at New York University to investigate the use of AI to speed up MRI scanning. “If we can get a 4X to 8X reduction in time, that’s a game changer from an economic standpoint, and from reaching a larger patient population,” says Schroepfer.

Don’t take FAIR’s foray into AI-enhanced healthcare as evidence that the company wants its research arm to be an Alphabet-style moonshot factory taking on an array of the world’s big problems all at once; Schroepfer says that it will choose only a few such non-core research areas to explore. For all FAIR has accomplished in its first five years—and all the ways Facebook has changed—its original mission still has plenty of headroom.

“I don’t think anyone who’s paying attention should be doing a victory lap yet,” says Schroepfer. “We’ve made stunning progress. But we’re nowhere near done, and every time we make a small improvement, it has massive impact on our products.”

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.