One of the main complaints levied against docked bike-share systems is that they’re notoriously bad at serving low-income neighborhoods of color. The borders of Citi Bike in New York and Capital Bikeshare in Washington, D.C., for instance, generally track along the edge of the more prosperous parts of the city, and skirt neighborhoods like East New York or Anacostia, where residents are poorer, less white, and in need of better transit options that current infrastructure provides.

One of the arguments for the free-range options,. like dockless bike-share e-scooters now on the scene, was that they would change this pattern. Because they don’t require the expensive and bulky docking infrastructure that earlier bike-share iterations rely on, dockless bikes and scooters can be deployed in greater numbers, and with greater flexibility around location. Minneapolis’ Nice Ride program, one of the earliest docked bike-share systems in America, is switching to dockless for its expansion for those exact reasons.

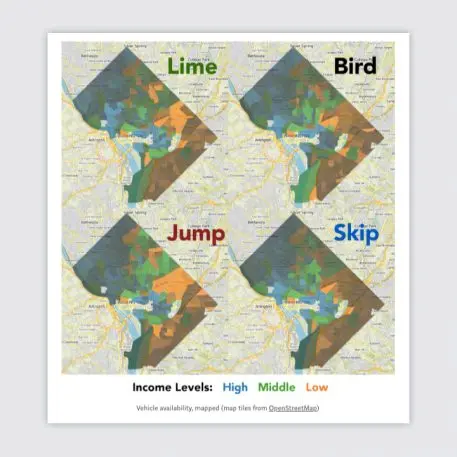

But the reality of the way dockless bikes and e-scooters are distributed often falls short of the ideal. In the Washington, D.C. area, the mobility data company Coord looked four different vehicle providers–Lime, Bird, Jump, and Skip–and analyzed how well they were serving census tracts across the socioeconomic spectrum.

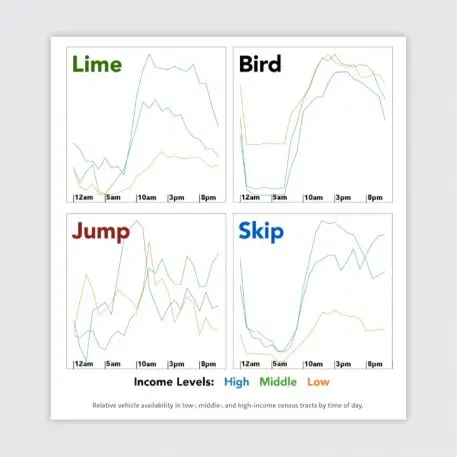

What Coord found, according to cofounder and CTO Jacob Baskin, was that each company followed a different pattern in how it distributed its vehicles across neighborhoods of varying income levels. Of the two scooter companies, Bird and Skip, Bird maintains a higher number of scooters in lower-income neighborhoods, and of the two companies (Jump and Lime) that manage both bikes and scooters, Jump serves lower-income neighborhoods much more successfully.

Washington, D.C. offered an ideal setting for Coord to test out his type of equity analysis. Recently, the District Department of Transportation announced that it would be expanding the pilot program that enabled various mobility companies to come to the city in the first place. In 2019, the city will grant companies a permit to deploy 600 bikes or scooters, up from 400 previously. Under the new terms of the permit, though, the companies must offer non-smartphone payment options for trips (to open access for people who do not have smartphones) and offer discounts to low-income people. They also must deploy bike and scooters in all eight wards of the city by 6 a.m.

What Coord wanted to figure out was what types of gaps mobility companies should be looking to fill under the new terms of the permits. Coord already collects and analyzes data on the distribution of different companies’ bikes and scooters (which the companies are required to make public). For this initial equity analysis, it was just a matter of Coord overlaying density of bikes and scooters with income level in various census tracts.

“These mobility providers all believe very strongly that they are benefitting everyone,” Baskin says. “But what they don’t have, almost ever, is any type of competitive analysis–they’re not in the habit of looking at their data in comparison to other companies.” And that lack of comparative analysis, Baskin says, is part of what contributes to excess availability in wealthier areas, that are already well-served, and a lack in lower-income neighborhoods.

Coord found that while Lime and Jump do a much better job at reaching lower-income neighborhoods, none of the four main mobility providers have a strong enough presence in Anacostia, one of the poorest parts of the city. Scooter companies like Skip and Bird have much stronger presences in wealthier areas of the city like Georgetown, and because e-scooters have to be charged overnight, availability in those areas drops dramatically at nighttime. In lower-income areas, the presence of what scooters there are doesn’t change as much depending on time of day, suggesting, according to Baskin, that either the companies are having trouble collecting the scooters to charge them, or they’re not being used enough to merit charging every night.

Coord published this analysis on its public blog, but has not, Baskin says, reached out to the individual providers in the study to discuss the findings with them. But as 2019 approaches and the companies will be under more scrutiny from the city to meet equity goals, this analysis should help them identify where to be. All of the companies, for instance, need to prioritize Anacostia and other lower-income areas, and the scooter operators in particular should perhaps look into doing outreach in less wealthy neighborhoods as part of their increased expansion there.

All four of these providers have presences in multiple cities, and the learnings from D.C. should encourage them to look more critically about how they’re performing on equity goals elsewhere. “We see this as a demonstration of why this data is so useful and so important,” Baskin says.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.