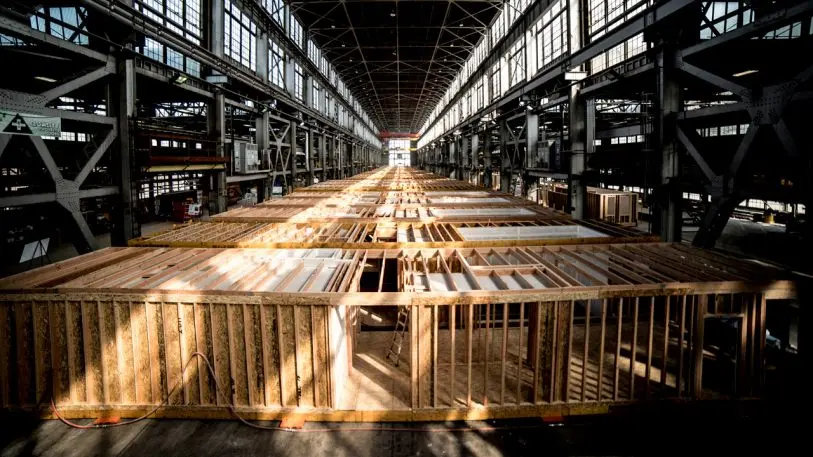

Inside a sprawling former submarine factory in Vallejo, California, workers are building individual apartments that will soon be delivered to a building site in West Oakland and stacked, Lego-like, into a new 110-unit complex next to a BART station.

The startup, called FactoryOS, is one example of a growing number of companies that are trying to tackle the affordable housing crisis by fundamentally changing how we construct buildings.

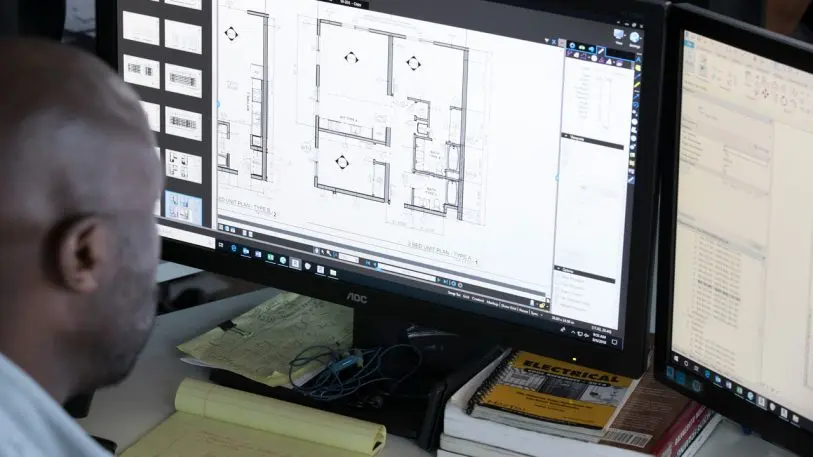

Each step of the process is designed to work as efficiently as possible. At one station, on a raised platform, workers lay flooring at table height, and then the platform rises so they can add insulation and plumbing below it. Down the line, others add walls and everything from toilet paper holders to appliances. At another station, a machine lifts 400-pound windows and sets them in a unit at ground height–a much simpler process than installing them from scaffolding on a six-story apartment. By the time the units get to the building site, only a few steps will be left, like adding exterior siding and roofing. FactoryOS says that it can provide housing at twice the speed and half the cost of a standard project.

“To simultaneously be able to fabricate units while site work is going on is just intuitively a massive timesaver,” says Adhi Nagraj, director of the nonprofit SPUR, the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association. Nagraj has developed two affordable modular developments himself, and says that it took less time and saved money to use a factory.

As I talk with Holliday, it’s raining outside; any outdoor construction in the Bay Area has stopped, but it continues inside the factory. With full-time employees on staff, the process can also continue without the typical delays of a standard construction project. The project in West Oakland, which might normally have taken two years, is likely to be completed in eight to nine months instead.

Working off-site is also cheaper. “Building in cities has just never been more expensive,” says Steve Glenn, CEO of Plant Prefab, a Southern California-based modular housing company. Land costs have gone up. Labor costs have also increased significantly; when the housing market collapsed in 2008, many construction workers left the industry and haven’t returned. In places like the Bay Area, the high cost of housing has pushed some construction workers to move away.

“Our first factory is about an hour and change outside of Los Angeles,” says Glenn. “We pay our guys a great living wage for Rialto, but they could earn two or three times that much an hour to the west. So that’s one way that we’re able to save money.” (The company, which is now part of Living Homes, Glenn’s older modular home company focused on sustainability, also makes high-end housing; one backyard house designed with Yves Béhar goes for $280,000.) With a new round of investment from Amazon and others in September, the company is now also working on a new house-building system that will use some automation, cutting costs further.

3D printing is another way to increase automation and reduce labor costs. “Land cost is the biggest driver of housing right now in the Bay, but labor is one of the areas where 3D printing is able to create cost savings,” says Sam Ruben, VP of compliance and sustainability at Mighty Buildings, a 3D house-printing startup that is currently in stealth. Icon Technologies, another startup that is beginning to work with a nonprofit to 3D-print ultra-low-cost houses in El Salvador, plans to begin working in the U.S. in 2019. The technology, which uses machinery to squirt out concrete or other materials to build floors, walls, and, perhaps soon, roofs–is another way to speed up one part of the construction process and make housing more affordable.

Of course, reducing labor costs also means impacting workers. “As someone who’s really a big fan of unions and really loves what they’ve done for this country and for workers, it’s an area I struggle with,” says Ruben. “We’re seeing it across the board with technology that’s really starting to impact whole swaths of jobs that traditionally have been unionized. There’s a conversation that needs to be had there about what it looks like to responsibly expand technology. That’s why we’re starting to see calls for universal basic income and other aspects that I think are going to be important as we as a society embrace the benefits of technology to really bring it to bear, particularly in an industry like construction that hasn’t changed in over 100 years.”

In Vallejo, FactoryOS has a contract with the local carpenter’s union, the biggest of the trade unions, which works to bring in “second chance” employees who have been through the prison system, among others. Workers earn less than they would onsite in San Francisco, but the work is steadier, comes with vacation time, and helps avoid a commute that is getting steadily worse as more people are forced farther away because of the cost of housing. Holliday says that some of his employees were commuting almost five hours a day; now, living in the relatively cheap city of Vallejo, they’re commuting five or 10 minutes each way. On-site work–from adding the foundation and roofing to landscaping–still requires higher-paid labor and typically longer commutes.

Another company, called Panoramic Interests, made the more controversial choice of using a factory in China to build its modular units. The company recently completed a student housing project in Berkeley, and it also aims to build housing for the homeless. The company has struggled with opposition from labor unions, particularly in San Francisco. (Other cities in the area have been more open to the idea of modular housing.) The City of San Francisco is now considering building its own modular housing factory inside city limits in order to use local labor.

Modular housing isn’t new; some early colonial settlers on the East Coast brought some prefab materials from England. A few centuries later, thousands of Americans built houses from Sears kits. Mobile homes have been built in factories for decades. But the current round of investment in factories to build urban homes is new, with a focus on developing new technology to support it.

It’s driven by “the acuity of the housing crisis,” in places like San Francisco, says Nagraj. “We’re seeing a lot more companies are leaving town. Homelessness is unbearable, and people are living on the streets. Kids of parents who grew up here are not able to buy or rent their own place. Between rent and healthcare, starting salaries have to be so high [for companies] that it is making the Bay Area less competitive. So I think part of it is the need that the marketplace is showing for cheaper, more efficient construction methods.”

A handful of other companies are also working on the next generation of factory-built housing, such as RAD Urban, an Oakland-based developer that is aiming to prove that high-rise buildings can also be affordable, if built differently than usual. Unlike some of the other modular companies, RAD is using steel-framed construction. It aims to build housing 25% faster, and 25% cheaper, than standard construction. Katerra, another Silicon Valley construction startup, has raised more than $1 billion, though its factory has suffered from delays–reportedly because of a lack of construction experience on its team. Blokable, a Seattle startup founded by a former Amazon employee, is working on an affordable housing complex for low-income and homeless residents on land that belongs to a church. In Chicago, a contractor named Skender has built another factory that will begin cranking out modular housing next spring. In Los Angeles, a startup called Cover uses software to design prefab backyard houses–another means of providing much-needed housing, especially in a city filled with single-family houses–for a minimal architects’ fee.

Construction technology, of course, is just one factor in the cost of housing in overpriced cities like San Francisco. Many other things also have to change, from zoning codes and protections for renters to the wages that people can earn at non-tech-related jobs. Some things also need to change to support the growth of options like modular or 3D-printed housing. Financing can be a challenge, for example. Fannie Mae, the government group that provides liquidity for mortgage lenders, is trying to encourage more financing to flow to innovative forms of housing. For a 3D-printed home, “a question a lot of people ask is how do you appraise that? How do you even think about underwriting and approving that?” says Jonathan Lawless, vice president of product development and affordable housing at Fannie Mae. “So there’s a direct way in which we can influence how we think about the collateral and how we value the collateral as part of the loan process.” (The organization is also encouraging the growth of backyard homes by letting homebuyers count the income from an “accessory dwelling unit” in a loan application, and adding the cost of building a backyard house to a loan.)

Fannie Mae, which recently co-hosted a conference on innovation in housing, believes that as more modular and 3D-printed buildings are built–if they can prove significant savings of time and money–it could help the housing stock grow more quickly. “We have not been building enough homes to support the population growth,” Lawless says. “So for us, the question is, if we really want to drive affordability, how do we help the industry leverage new technologies like 3D printing to make building homes easier and cheaper?”

The industry is overdue for a change, he says, and others agree. “How we build buildings has not evolved much in the last 50 years, whereas how we build cars and phones and everything else has had massive technological innovation and change,” says Nagraj. “So I’m excited that there is more innovation in the building industry.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.