Dictionary.com’s choice for word of the year has become every bit as much of a bellwether as Time magazine’s person of the year. And this year–more so than in years past in my opinion–the editors at Dictionary.com nailed it with their choice of “misinformation.”

My first reaction, however, was: “Wait, why ‘misinformation’ and not ‘disinformation’?” which I’ve heard, read, and written about more often since November 7, 2016. Turns out there’s a very good reason.

Dictionary.com defines misinformation as “false information that is spread, regardless of whether there is intent to mislead.” Disinformation, on the other hand, is defined as “deliberately misleading or biased information; manipulated narrative or facts; propaganda.”

Note that the definition of “misinformation” still leaves open the possibility that the spreader has an intent to mislead. In other words, “disinformation” implies a definite intent to mislead, while “misinformation” makes no implication about intent.

Note that the definition of “misinformation” still leaves open the possibility that the spreader has an intent to mislead. In other words, “disinformation” implies a definite intent to mislead, while “misinformation” makes no implication about intent.

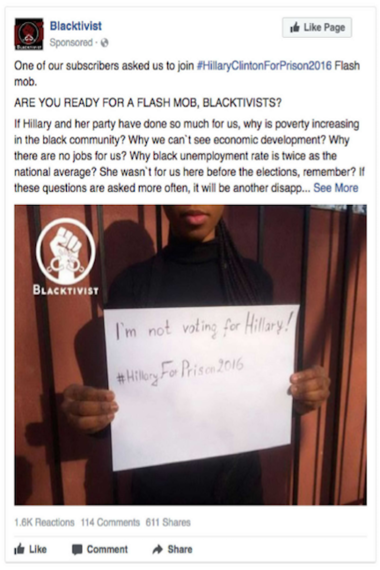

It’s possible for a message to start out as disinformation and turn into misinformation. When it comes to the Russian troll who posts on Facebook about Black Lives Matter members hating on Hillary, that post is disinformation. But for the person who shares the message because it agrees with or affirms his existing world view (aka, confirmation bias), that’s misinformation.

The choice of misinformation as word of the year is brilliant for lots of reasons. Disinformation isn’t dangerous unless it’s propagated as misinformation.

The term also captures the tragic flaw in today’s dominant form of communication–social media. For much of its life Facebook was just a nice way to keep in touch with old friends and share baby pics with grandma. Twitter was once mainly about pithy quips and food pics. Now our social networks–especially Facebook–are vast and lightning-fast influence platforms that often deal in hate and half-truths. And there’s no built-in mechanism in social networks for shutting down misinformation, no immediate sanction for spreading it.

“One of the more unnerving things to realize is that there don’t seem to be any consequences,” said Ed Wasserman, dean of the graduate school of journalism at Berkeley. “There’s no reprisal; there’s no reputational harm. Falsity has now been woven in to the fabric of what political discourse looks like.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.