New York Media, the parent company of New York Magazine, is the latest media company to join the software licensing bandwagon. In an increasingly competitive industry–where revenue streams rise and fall like unpredictable monarchies–organizations have sought new ways to rely less on content churn and advertising. Those that have built their own proprietary technology have found an opening.

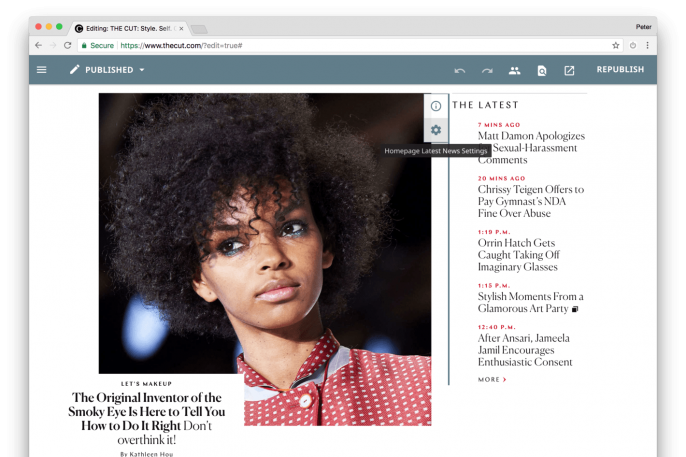

The company behind the beloved biweekly magazine—and a series of popular branded verticals like The Cut, Vulture, and Daily Intelligencer—has been using its own publishing platform for many years, and now others are beginning to pay for it, too. The first to test it out was Slate, which used New York Media’s software to build out its most recent website redesign earlier this year. Now two others media organizations have inked licensing agreements: Golf.com and Entercom’s Radio.com.

A “closed, open-sourced network”

According to Daniel Hallac, New York Media’s chief product officer, the company has been thinking about selling its own technology for a while now. Some years back, it built its own publishing platform after deciding that Adobe CQ—which New York Media’s sites were previously built on—wasn’t robust enough for the magazine’s digital ambitions. New York Media’s engineers devised their own program and named it Clay (after one of the magazine’s cofounders, Clay Felker, as well as the idea of software that can “mold”).

Hallac describes Clay as built with adaptability in mind. The overall idea, he says, was to make it “as future-proof as possible.” What’s more, it’s a “component-based platform.” Hallac describes it like a Lego set that allows developers to add in whatever new components they want. The architectural philosophy, he explains, is to have a platform that lets the company easily add new components on both the front and back ends.

The transition from individually bespoke software to potential revenue driver was slightly haphazard. Much of Clay is open-sourced, and so when word got out that Slate was unhappy with its content management system (CMS), the two media companies decided to test out a partnership. First, Slate built its long-form features on Clay to see if it liked the new system. The test worked, and so Slate signed a deal to license Clay for its entire redesign. This first test, says Hallac, “really opened our eyes to the possibility” of selling more of these licenses.

“What I think makes our CMS and model unique is that [clients are] not buying what we have,” Hallac says. “The way Clay works is that licensees are part of a closed, open-sourced network.” In a sense, all the customers are part of a consortium building their own things. The Clay codebase is shared among all of them, but they fork it and then build whatever they want atop it themselves.

Selling software is all the rage

Though Hallac maintains that Clay is a different sort of service than your average CMS, this business move certainly falls in line with a broader media trend. Vox Media, for instance, has been pushing its Chorus software—which offers both a CMS and an ad network. (New York Media is not selling any sort of advertising network products besides the ability to put ads on a site.) The Washington Post, too, has its own platform, called Arc, which is being licensed to newspapers around the world.

Differences aside, the idea and price model is generally the same. Media companies find licensees who shell out monthly fees. For the Post, the fees range from $10,000 to $150,000 per month. Vox Media’s fees are reportedly in the “six- and seven-figure ranges,” according to the Wall Street Journal. Hallac doesn’t publicly disclose what New York Media charges for Clay, but the software suite offers less comprehensive services than the other two, so it’s probably less steep.

With three clients, the Clay operation probably isn’t making a significant dent in the media company’s revenue pie chart. But it’s one of the new ways that the legacy magazine is trying to diversify during these tough media times. To that end, New York Media announced earlier this week that it plans to introduce a metered paywall—another trend that has been sweeping the ecosystem for the past few years.

In some ways, these announcements seem carefully timed to make the media company look like an enticing acquisition. In fact, Pamela Wasserstein, New York Media’s chief executive, told the New York Times that it has received some offers. Growing subscribers while showing the ability to grow other revenue engines is absolutely one way to bring on more suitors–so who knows what the future holds.

For Hallac, this year’s foray with Clay has been a way to prove it’s a good market fit, as well as show off its myriad capabilities. Now that publishers seem at least interested, he sees the potential for some real revenue. “We are definitely looking to grow,” he tells me. “We’re really curious to see what new uses we and our partners will come up with [using] this new tech.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.