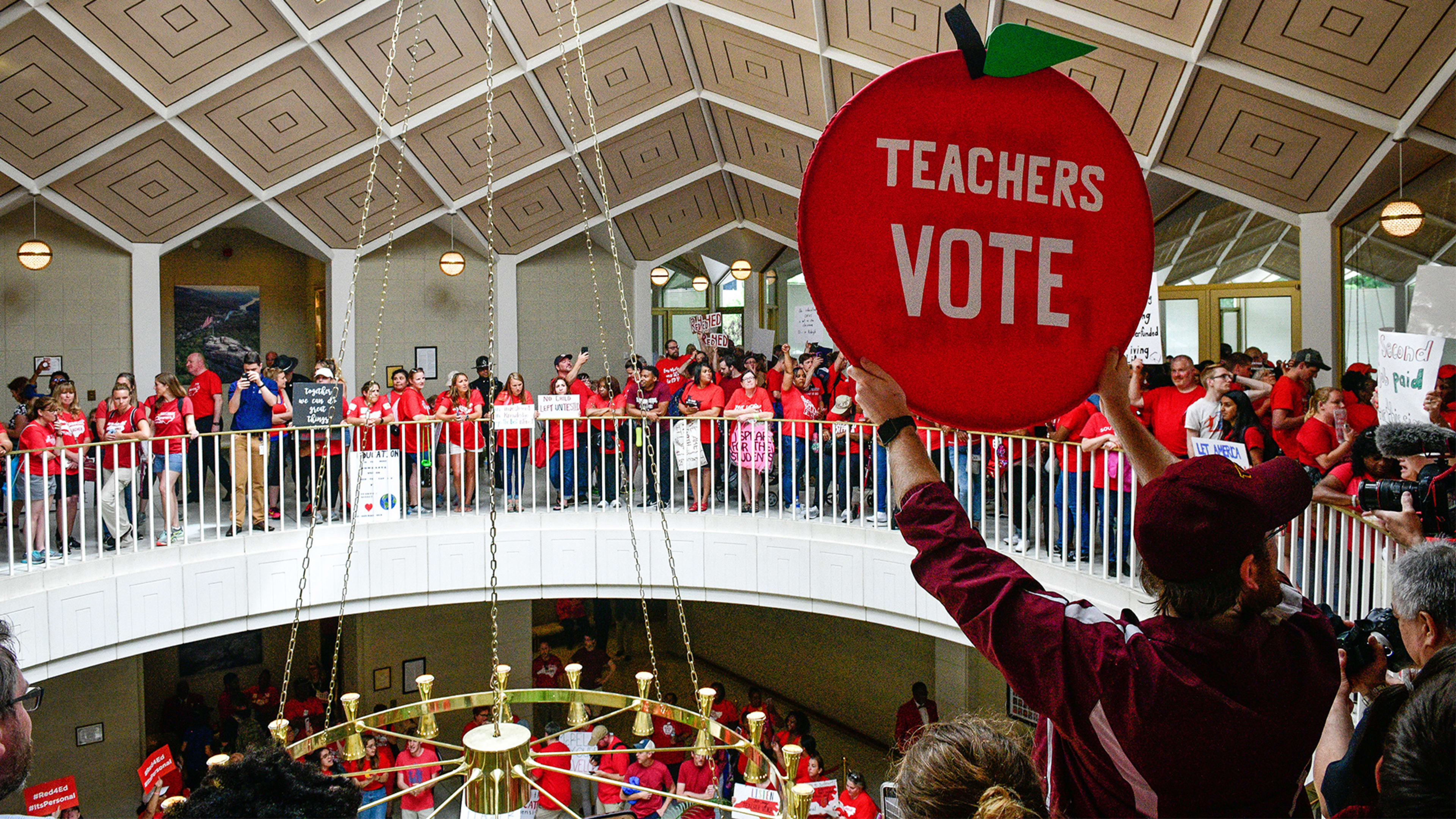

As the teacher strikes that drew national attention in the spring in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona wound down, they left elected officials and all those watching with a phrase: “Remember in November.” The walkouts in all three states began in response to decisions by Republican-led state governments that gutted public education funding. In the decade leading up to the strikes, teachers’ salaries stagnated and their benefits dwindled as states constricted their public education budgets. Teachers’ unions, their power diminished by anti-union laws passed by those same governments, weren’t able to effectively fight back against the cuts–until the strikes.

After the strikes, many of the same teachers worked to get on the ballots for the midterms in November. Their goal: To flood state and local governments with educators who have felt the adverse effects of years of budget constraints, and who would use their political standing to advocate for better funding for public education. As one educator, Heather Deluca-Nestor, president of the Monongalia County Education Association in West Virginia, put it: “We want to flip some seats so we’re protected, so education is protected, so public employees in West Virginia are protected.”

Galvanized by the strikes and the national spotlight on public education, an unprecedented number of teachers ran for office in 2018. “Normally, we have around 100 members run–this year, it was easily 300,” says Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), one of the leading teachers’ unions in the U.S. Of the 178 finalized elections in which AFT teachers ran, they won 109, as of the most recent count. Most who ran were Democrats, but several were Republicans, Weingarten says, which reflects the growing bipartisan reach of the issue. The National Education Association (NEA), the other large teacher union in the country, counted 1,800 educators who ran in the midterms; 1,080 of them were elected to their state legislatures. “You have a lot of people who proudly wore their teacher pedigree and what it stands for–which is hope and opportunity–on their sleeves, and it was embraced,” Weingarten says. “People want people in office who will problem-solve, and will solve their issues.”

As the dust settles after the November 6 elections, it’s clear that the spotlight the teacher strikes directed toward the dire state of public education in the country had an effect. In Oklahoma, bolstered by the wins of former teachers like Carri Hicks, Jacob Rosencrants, and John Waldron to the state legislature, the state’s “education caucus”–a group of bipartisan lawmakers committed to improving education–grew from nine members to 25. Mobilizing around education this spring helped Democratic candidates break the Republican supermajority in North Carolina last week.

While the teacher strikes did not reach Wisconsin in the spring, voters there got the message, and in the governor’s race elected Tony Evers, a former teacher and superintendent, over longtime public education foe and right-to-work proponent Scott Walker. Tim Walz, a former high school teacher, became governor of Minnesota. And in states where educators themselves were not running, it was still a winning issue: Gretchen Whitmer was elected governor of Michigan after campaigning against public-school funding cuts (a significant achievement in the home state of Betsy DeVos). In Illinois, Democrat J.B. Pritzker unseated the anti-public-education governor Bruce Rauner. And in Kansas, where school districts successfully sued the state for more funding, Laura Kelly defeated conservative incumbent governor Kris Kobach on a platform of further expanding funding for public schools.

In the lead-up to the general election, education became the second most-mentioned topic in both Republican and Democratic campaign ads. While the tax cuts that gutted public education emerged from Republican policies–tax cuts for corporations, and an insistent opposition to funding public resources–Republican candidates seeking election (or re-election) began to co-opt the idea of improving public education in the wake of the teacher strikes. Notably, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, after teachers walked out in his state, played up the public education funding expansion that emerged out of the strikes in his ultimately successful re-election campaign. Kevin Stitt, a Republican who won the governor’s seat in Oklahoma, also made increasing funding for public schools a central tenet of his campaign after walkouts in the state.

There were, however, also some notable losses: Richard Ojeda lost his bid for the U.S. House in West Virginia after championing education reform (though he’s reportedly launching a bid for president). Legislatures and governorships in those states remain Republican-controlled. To Weingarten, though, this is not a defeat for the movement, but rather the beginning of a long, slow process that is just getting started. “The intensity of the walkouts in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona may not have led to sweeping victories in November,” Weingarten says. “But looking at the losses alone doesn’t account for how much bridge building we need to do given how deep a hole public education has been in under decades of Republican control.”

What the strikes accomplished was making the need for improved public education impossible to ignore, Weingarten says. “We have to start this discussion by going back and saying: Why did teachers walk out?” If those reasons–low salaries, poor benefits, overburdened schedules–don’t improve for the better, Weingarten says, teachers will not remain quiet, and will continue to agitate for change, both inside and outside of state houses, until they do. Voters have galvanized around these issues, too: The NEA found that apart from educators who ran, members and their families showed a 165% increase in activism and volunteering around the election over 2016–especially significant because midterms tend to mobilize fewer people than general elections.

Furthermore, every teacher who did not win their election this year will be keeping close tabs on the people making decisions about education in their state. In Oklahoma, for instance, Stitt’s promise to improve education–and deliver a “top 10” education system for the state–makes no mention of erasing tax cuts on corporations to correct decades of disinvestment and lack of funding. If Stitt’s plan fails to deliver, the Oklahoma “education caucus,” already empowered this year, will likely grow larger as teachers continue to run to hold him accountable. And Mike Collier, a Democrat who lost a long-shot campaign for lieutenant governor in Texas after incumbent Dan Patrick began running ads about his promise to boost teacher pay, has promised to hold Patrick and the state of Texas accountable to those promises. Ultimately, it seems the teachers’ strikes opened voters’ eyes to the fact that public education in the U.S. is something within their control, and if they want to see it improved, they can run to change it, or they can vote for candidates who promise that change. This year, Weingarten says, was just a first step.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.