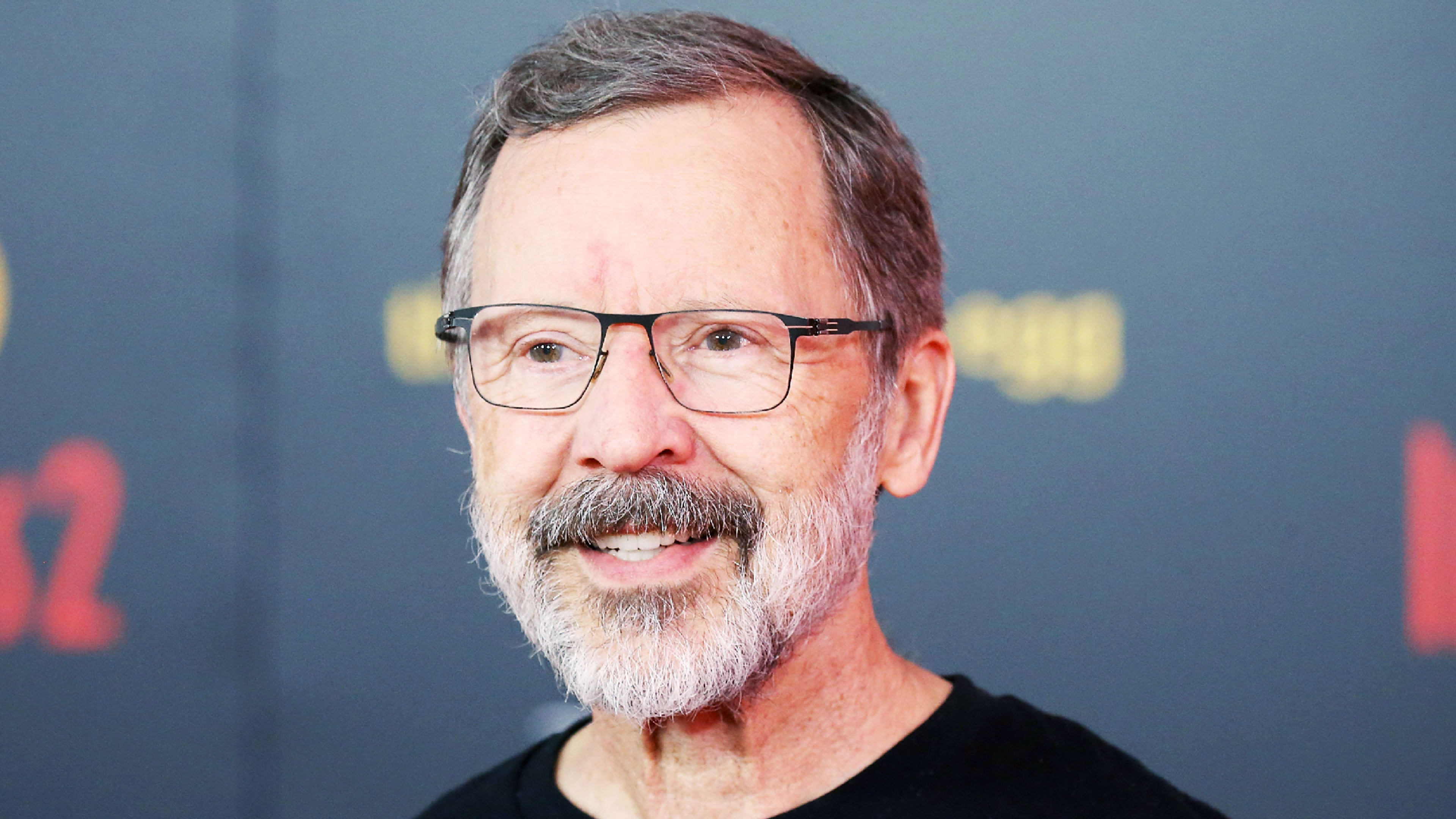

Ed Catmull, one of the founders of Pixar, has provided leadership to that company for over three decades in a very special way. More recently, with Pixar’s merger with Disney, he became president not only of Pixar but of Walt Disney Animation Studios. As a longtime student of leading innovation, I’ve tried to learn from his constant, passionate efforts to cultivate both of these hotbeds of creativity.

We have had many conversations about how his philosophy of building cultures of candor aligns with my own deep belief that, if an organization wants better answers, it must get better at asking questions. When he agreed to write the foreword to my new book on that subject, I regarded it as an immense gift. With his recent announcement that he will be retiring in the coming year, his thoughtful comments are a gift I wanted to share even more broadly. The following is an excerpt from Questions Are the Answer: A Breakthrough Approach to Your Most Vexing Problems at Work and in Life.

–Hal Gregersen, MIT Leadership Center and MIT Sloan School of Management.

When I visited Hal Gregersen recently at MIT, he told me something about Pixar and Disney Animation that I hadn’t actually thought about—despite having spent a lot of time thinking about how we do things. In fact, Hal had my book describing Pixar’s way of working, Creativity, Inc., in his office. To say it was dog-eared would be a serious understatement.

“You are constantly asking questions in that book,” Hal told me. “It’s full of questions.” More broadly, he said, based on his visits with various colleagues of mine, that our people are great at asking “catalytic questions” of each other. “It’s like you have this disciplined instinct, or learned habit, that has you constantly operating under the assumption that ‘I don’t know things that I need to know.’ And then you figure out ways to get them to surface.”

Assembling a brain trust and encouraging candid feedback

I recognized what he was talking about. At Pixar, we have developed several ways, I would even call them institutions, over the years for pushing ourselves, our stories, and our filmmaking into new creative territory. For example, our directors all know that at any point in a project when they are feeling stuck or could use some fresh eyes on work in progress, they should assemble the “Brain Trust” of their peers to challenge their thinking.

This is not just a random, ad hoc gathering. Brain Trust meetings follow a particular process and have a set of norms around them that we have refined over the years to help the director see new creative possibilities but not rob that director of control. When we merged with Disney, we found we could translate practices that worked in Pixar’s environment to the other side of the house—so, for instance, there is now an equivalent to Pixar’s Brain Trust, called “story trust,” in the Disney Animation world.

Putting elements like this in place to make creative collaboration more possible is the most important work I can do at Pixar and Disney Animation. (Probably, the same could be said for any manager of an organization that depends on producing a steady stream of innovative work.) Everything depends on the quality of our creative output, and it always improves from candid feedback offered in the spirit of mutual commitment to excellence. A lot of things go into creating the conditions for this, but perhaps the requirement that deserves the most careful thinking is making it safe for people to speak up about problems and offer ideas for how to solve them.

Separating self-worth from the worth of ideas

It probably goes without saying that for this sense of safety to exist, the focus has to be kept on the problem and the need to solve it, and not on the person who has failed to solve it so far or the people volunteering suggestions. But even when the focus is wholly on the problem—like, what would make this character more compelling?—any constructive reaction to the work in progress or a comment made about it implies at least some level of dissatisfaction or rejection. And it can really sting. For workers in creative roles, it is very hard to separate their sense of self-worth from how others perceive their capacity for problem-solving.

So, for the person who is in the position of overseeing a group’s work, the best thing to figure out is how to remove that perceived risk that people will be judged for speaking up. How do you create the conditions in which colleagues will rigorously judge an idea that has been put out there, but not judge each other for suggesting the ideas? How do you get to a point where ideas that don’t work aren’t themselves personalized? Logically, this has to happen for ideas to rise and fall on their merits, but emotionally, it is just profoundly counterintuitive.

So this is the context in which I heard Hal make his comment about my colleagues’ questioning skills. I think intuitively we probably have gravitated toward the kinds of questions he likes to call catalytic—the kind that knock down barriers by challenging past assumptions and create new energy for pursing solutions along some new pathway. And if we have, it is probably in part because asking a question is a very effective way of introducing a novel way of thinking about something without exposing oneself to judgment.

A question, after all, is not a declaration of opinion aggressive enough to draw fire—it is an invitation to think further within a different framing or along a divergent line. If that line of thinking isn’t taken up, or fails to lead somewhere valuable, there is no reputational damage to the person who suggested it. And, therefore, a person is more likely to put it out there.

It is interesting when someone holds a mirror up to you and your organization and allows you to recognize something you had not thought about in quite the same terms. I think Hal is right that a certain kind of questioning is present in my colleagues’ creative collaboration, and I am now paying more explicit attention to it.

Mission questions instead of mission statements

Thinking about the power of questions in collaborative, creative work, I will make one more point. As my colleagues all know, I have never been a fan of organizational mission statements. It isn’t that I am against having a collective sense of purpose—any time people are working together in a formally organized way, they should be thinking deeply about why they do what they do. But my exposure to the mission statements that top management teams unveil to their organizations is that they always represent the endpoints of discussions and actually stop people from doing any deeper thinking.

I see better now what bugs me about them: They sound too much like answers. I think it might be better to have mission questions—or at least mission statements that are so ambiguous that they cause people to actively wonder: “What does that really mean?”

When we see the point of our work as all about arriving at smart answers, too often we mistake an answer for the end of an effort. We celebrate arriving at a point from which we need go no further. But that isn’t the way life is. Yes, often we are hard at work producing something that needs to be finalized—in Pixar’s case, at some point, we release a movie. Boeing ships a jet. A professor finishes a book. And that is an important form of culmination. But for many people, I think, that culmination becomes the goal.

What if, instead, we valued the answers we arrive at mainly because of all the new and better questions they lead us to? Put another way, what if instead of seeing questions as the keys that unlock answers, we saw answers as stepping stones to the next questions? That strikes me as a very different mind-set—and one that could take the creative efforts of groups much further.

Ed Catmull is the coauthor of the New York Times best seller Creativity, Inc. and president of Pixar Animation and Disney Animation.

From the book Questions Are the Answer: A Breakthrough Approach to Your Most Vexing Problems at Work and in Life by Hal Gregersen. Copyright © 2018 by Hal Gregersen. To be published on November 13, 2018, by HarperBusiness, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.