Stand on Surf Avenue and there’s little evidence that in October 2012, a nearly 14-foot storm tide broke across the Coney Island boardwalk, merging with water from Gravesend Bay and Coney Island Creek, and violently surged across the fragile peninsula from all three sides. Hurricane Sandy’s life-threatening storm sent cars floating down dark, flooded streets and left thousands of residents without light, water, or heat. It left others marooned on upper floors of apartment houses and public housing towers in the neighborhood’s West End. In neighborhoods as close as Bensonhurst, it was business as usual, almost as though there’d been no hurricane. But in Coney Island in the hours and days after, people resorted to eating food tainted by sea water and collected water from hydrants, as sinkholes big enough to crawl through opened from one end of the block to the other.

Six years after the storm killed 43 New Yorkers, and caused $19 billion worth of damage to the city, the boardwalk attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists to its glittering amusement park featuring log flumes, roller coasters, and high-end restaurants. But for residents of the area, it’s a different story. The still-glacial pace of repair in Coney Island has meant many New York City Housing Authority buildings are still in bad shape, while some residents are only now moving back to homes rebuilt by a troubled federally funded reconstruction program. It’s the gleaming mixed-use buildings full of market rate apartments breaking ground on Surf Avenue, and others rising near Sea Gate at Coney’s western tip, that alarm advocates, city planners and locals. They say Coney’s dramatic building boom, triggered by a Bloomberg-era 2009 rezoning, but slowed by Sandy recovery, suggests a dangerous amnesia about how the storm devastated Coney. And a denial about the threat that rising seas and bigger, more dangerous storms caused by climate change pose to this former barrier island.

Managed (or strategic) retreat is a climate strategy that calls for pulling back from coastal areas and letting them revert to nature, while moving residents to higher ground. It’s been part of the conversation since Sandy. The Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery bought out three perpetually inundated Staten Island neighborhoods, demolished the houses, and let nature take over. But in New York City, that still feels like an anomaly. “What we’re doing now is buying time,” says Robert Freudenberg, RPA’s vice president of energy and environmental programs. “We put more sand on the beach, make the walls higher, all these investments to make people feel safe. And in this phase we’re in, of buying time, should we be putting people in harm’s way?”

New Yorkers with means appear willing to take the risk of living in a flood zone in exchange for a good view. In July, data from FEMA flood insurance maps, the Department of Buildings and Localize.city, revealed that 12% of new construction in New York City is concentrated in high-risk flood zones, with the biggest share in South Brooklyn including Coney Island. “It’s all profit for developers,” says Maria Rotella, a lifelong Coney resident whose parents rode out Hurricane Sandy holed up in their Sea Gate home. “You ask people moving to Coney Island if they’re worried about it being underwater in eighty years and they’ll say ‘Eh, I’ll be dead by then.’ ”

Rotella doubts people moving into the new developments are thinking about Sandy or future storms. Or about the future at all. “The lure of living on the beach is just too strong,” she says.

Requiem for a dream

In 2009, when Mike Bloomberg’s hard-won rezoning package was approved by the City Council, no one could have predicted Hurricane Sandy or foreseen how it would telegraph Coney’s geographic vulnerability and economic inequities. Targeting the boardwalk on the edges of one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, Coney’s West End, Bloomberg sought to revitalize Coney Island through the development of its vacant and underutilized land, establishing an area bordered on West 24th Street, Mermaid Avenue, the New York Aquarium, and the boardwalk. He also ensured that 12 amusement park acres on parkland owned by the city would be protected from development, allocating an additional 15 acres for “complementary uses.” Since then, the amusement area has been developed; its new rides, restaurants and exhibits make it a huge draw for visitors. An estimated 7.4 million people visited Coney Island last summer, many of them riding the Wonder Wheel and the Thunderbolt in addition to availing themselves of the beach.

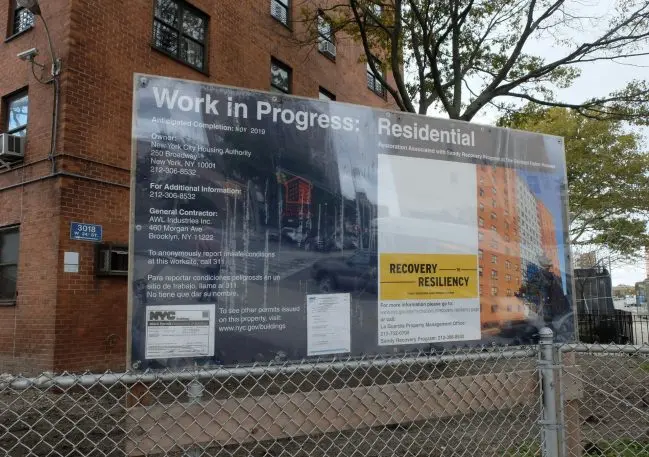

The city has poured billions into Sandy recovery in Coney Island and into future storm defense and preparation. The money is being spent on renovating Coney Island Hospital (battered by Sandy) and on hardening infrastructure and funding studies on areas of risk like Coney Island Creek. In 2013, it allocated $294 million for resiliency projects and received $13 billion from the federal Hurricane Sandy relief bill. New building codes approved by New York’s City Council require sea level rise and storm surge protections and impose new standards for developers operating in floodplains. Neptune and Cropsey and Mermaid avenues are being upgraded; Surf Avenue is being elevated by 3 feet.

OneNYC, the de Blasio administration’s expansion of Bloomberg’s environmental program, PlaNYC, strategically linked the city’s biggest challenges: population growth, aging infrastructure, inequality, and climate change. “We are putting in place comprehensive resiliency measures all across New York City to adapt to the impacts of climate change and help build a fairer city for all,” a City Hall spokesman said in an email to Fast Company. “In Coney Island, the City has invested millions of dollars to help residents recover from Sandy by rebuilding stronger, more resilient homes while working to ensure that the coastline is better equipped to withstand rising seas and extreme weather.”

But residents like Ida Sanoff say the city hasn’t done enough to protect Coney Island and neighboring Brighton Beach, where she rode out Sandy, from the next big storm. Much less from the rapid changes that are coming with rapid sea level rise. Sanoff is executive director of the Natural Resources Protective Association environmental watchdog group. “What’s been done since Sandy,” she asks rhetorically? “Absolutely zero. They put a little more sand on the beach, which has already eroded. I’d say we have enough sand left for a Category 1 Hurricane. Anything stronger than that, or worse than that, and the water is coming over the boardwalk.”

Storm clouds on the horizon

The water that’s coming is only one element of the bigger, darker climate change picture. Even before Hurricane Michael savaged the Florida Panhandle and Hurricane Florence slammed into the East Coast, dumping record amounts of rain and triggering catastrophic inland flooding in North Carolina, the globe’s other extreme weather events–fire tornados in California, record-breaking temperatures in Europe, the days when the Arctic Circle was hotter than New York City (and actually on fire)–signaled that the planet is being irrevocably altered by unchecked human activity. “What’s so alarming and real about the climate threat is that it’s no longer a prophecy,” says District 47 Council Member Mark Treyger, who represents Coney, Bensonhurst, Gravesend, and Sea Gate. Treyger co-created the council’s Recovery and Resiliency Committee after Sandy. Last year, he was behind the creation of a new task force to fully assess the city’s Sandy recovery to date. This is real. And the threat is increasing by the day.”

Treyger successfully petitioned to include Coney Island and Southern Brooklyn in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Rockaway Reformulation Study, potentially making Coney Island eligible for federal resiliency dollars. But his frustration over the lack of a comprehensive regional climate plan is obvious. “Even if there was consensus on how to protect Southern Brooklyn, there’s no money for any of it. I’ve appealed to federal partners–Schumer, Gillibrand, Hakeem Jeffries in the House. Staten Island was able to get money because they had coastal studies going back decades. For Southern Brooklyn, there was no analysis until we insisted that the Army Corps of Engineers include it in their study. That’s how far behind Southern Brooklyn was.”

What’s perceived as a piecemeal climate strategy bothers Ron Shiffman, too. Shiffman is a former member of the New York City Planning Commission and a professor at Pratt’s Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment. He believes OneNYC is moving in the right direction from a planning perspective, but that there’s a disconnect between the city’s planning and development functions, which prevents the city from realizing a truly comprehensive climate change policy. “We have to have a much more comprehensive plan that involves managing water. In my mind, what we have now is unconscionable. As is this ad-hoc development in places like Coney Island and the message it’s sending and the danger it’s creating for everybody there. As our memory of 2012 has ebbed, it’s easier to get financing for doing things we shouldn’t be doing.”

“Take your Go bag and run for your life”

Coney residents watching the new construction point to derelict Mermaid Avenue, the run-down commercial corridor that has been described as London after the Blitz. According to a Commercial District Needs Assessment, Coney’s three major commercial corridors–one of which is Mermaid Avenue– have an 11.5 percent storefront vacancy rate, almost twice the city’s average. “Building new luxury apartments here is like fixing your hat when there’s a hole in your boat,” Jaime Cartagena, a graduate of Liberation High School on West 19th Street, said recently. “Look around, there are 33 empty storefronts on Mermaid Avenue. We don’t even have a rec center. We need things like community centers in the West End, places for kids to play.”

Treyger believes one of the most effective ways to reduce flood insurance costs is to invest in resiliency and flood mitigation through a fully funded and comprehensive climate plan. “The more time we waste, the more these storms will impact the poorest and most marginalized, the most vulnerable, both financially and coastally,” he says. “It makes me sick to my stomach.”

This past summer, the Army Corps of Engineers sought public comment on a variety of flood protection designs for New York City and surrounding areas, referred to as New York-New Jersey Harbor and Tributaries. In a conference room at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, images of Rotterdam’s renowned flood system were projected on the wall, implying that something akin to it might also protect New York City against flooding. There was no mention of the fact that the Dutch have retreated from the coasts as part of their flood control strategy. Or that they’ve allowed certain areas to flood and are planning not on a 100-year basis, but on a 1,000-year basis.

To some in the audience, the Corps didn’t appear any closer to solving the problem of rising seas and inundation than they were in 1972, when they proposed building a 15-foot-tall sea wall made of concrete pilings and steel sheets that would stretch from Manhattan Beach to Sea Gate. After the presentation, Ida Sanoff summed up the city’s plan for coming climate-related disasters: “It’s basically ‘take your Go Bag and run for your life.’ ”

Classic adaptation strategies–building defenses against the sea, fortifying homes but also relying on federal money to build back after a storm–are unrealistic without also employing more radical approaches. Jesse Keenan, of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, says transformative adaptation will mean having to think about what to protect and what to let go. “To do something about climate change means that we’re going to have to move people. While work is being done behind the scenes, there isn’t a human being in elected office or in public authority in the city or state of New York who’s willing to stand up today to publicly say transformative adaptation is in the long-term interest of the people.”

Are Sea Gate, Coney Island, and Brighton Beach defensible in the face of the probabilities associated with climate change? “Absolutely not,” says Keenan. “It’ll be a completely spatial segregation of the haves and have nots around their buildings’ engineering capacity and the weather.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.