In the late 19th century, Arctic mania gripped the world. Explorers raced to discover the North Pole, and some held that they’d find a paradisiacal lost civilization there–before explorers arrived in 1909 to find a frozen ice cap.

Little more than a century later, the Arctic is in the midst of “the most unprecedented transition in human history,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, spurring another international race to control the top of the world. The rapid loss of ice in the Arctic is transforming life for the people and animals who live there and amplifying rising temperatures all over the world. Indigenous peoples are struggling to maintain their traditional livelihoods. Without ice to protect them from erosion, coastal communities are literally falling into the sea. Countries like Russia, Canada, and the United States are moving to develop their military capabilities to take advantage of the newly opened polar sea–and lay claim to the oil, gas, and mining resources there.

“To put it into context, the latest prediction are that the Arctic Ocean will be ice-free in the summer in 12 years time,” says Dutch photojournalist Kadir Van Lohuizen. “Which also partly explains the heightened military activity, because suddenly Arctic nations like Russia, Canada, the U.S., et cetera, in the future will be very close neighbors.”

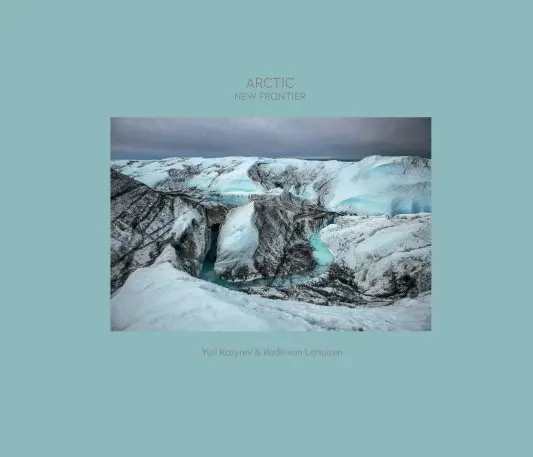

The Arctic is literally a new frontier–which makes it an appropriate title for the ambitious six-month project recently completed by Van Lohuizen and fellow photojournalist Yuri Kozyrev.

The Carmignac’s Photojournalism Award has been around for almost a decade, but this was the first time two photographers have ever won the award in a single year.

For Kozyrev and Van Lohuizen, it meant planning a long journey through highly regulated and virtually inaccessible sites during the Arctic summer. It took Kozyrev through sprawling mining operations and areas where melting permafrost is uncovering mammoth tusks (and splintered remains of the Gulag). On board a container ship that had completed the first route from Europe to Asia without help from icebreakers, he visited the coastal town of Murmansk, where Russia is building a floating nuclear power plant.

Meanwhile, Van Lohuizen visited scientists studying Greenland’s ice as it melts, and lived with an indigenous family in Point Hope, Alaska, where whale hunting is becoming vanishingly difficult as the ice melts: In one image, a hunter stands atop a pinnacle of ice, surveying for whales that are “almost impossible” to hunt as the ice melts earlier and earlier. In Resolute Bay, he photographed Canadian Army training facilities where the government stages its “annual sovereignty operation,” Operation Nunalivut, designed to ensure its “ability to adapt to a changing security environment.”

The trip him to towns like Kivalina and Barrow, Alaska, where the lack of sea ice is exposing the coastline to extreme erosion: Within less than a decade, Kivalina may be underwater and its residents will be climate refugees. In Siberia, Kozyrev traveled with the indigenous Nenet people, who have migrated seasonally with their reindeer herds for centuries. One photo captures a Nenet family herding their small flock across snowmelt. “For the first time in 2018, because of the melting of the permafrost, they were unable to complete their transhumance,” explains the caption.

The photos in Arctic: New Frontier feel like a blast of cold air, a sharp warning and bellwether of what’s to come for the rest of the world. In another few years, the landscapes that Kozyrev and Van Lohuizen documented this summer may be completely transformed–with only photographs like these to remind us of what the Arctic was like before the great melt was complete.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.