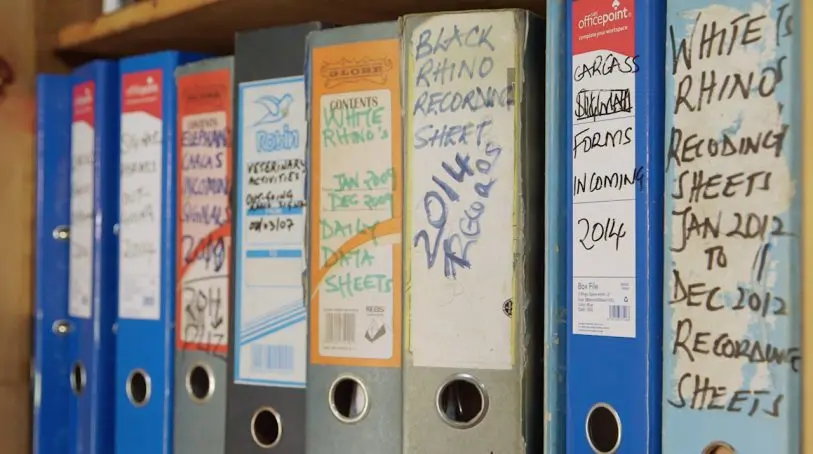

Until recently, park managers at Gonarezhou National Park in southeastern Zimbabwe, a sprawling reserve a little larger than the Grand Canyon, used push pins and colored dots on the wall to track poachers–moving the pins when rangers called in with reports of gunshots or footprints, and attempting to track the position of every ranger.

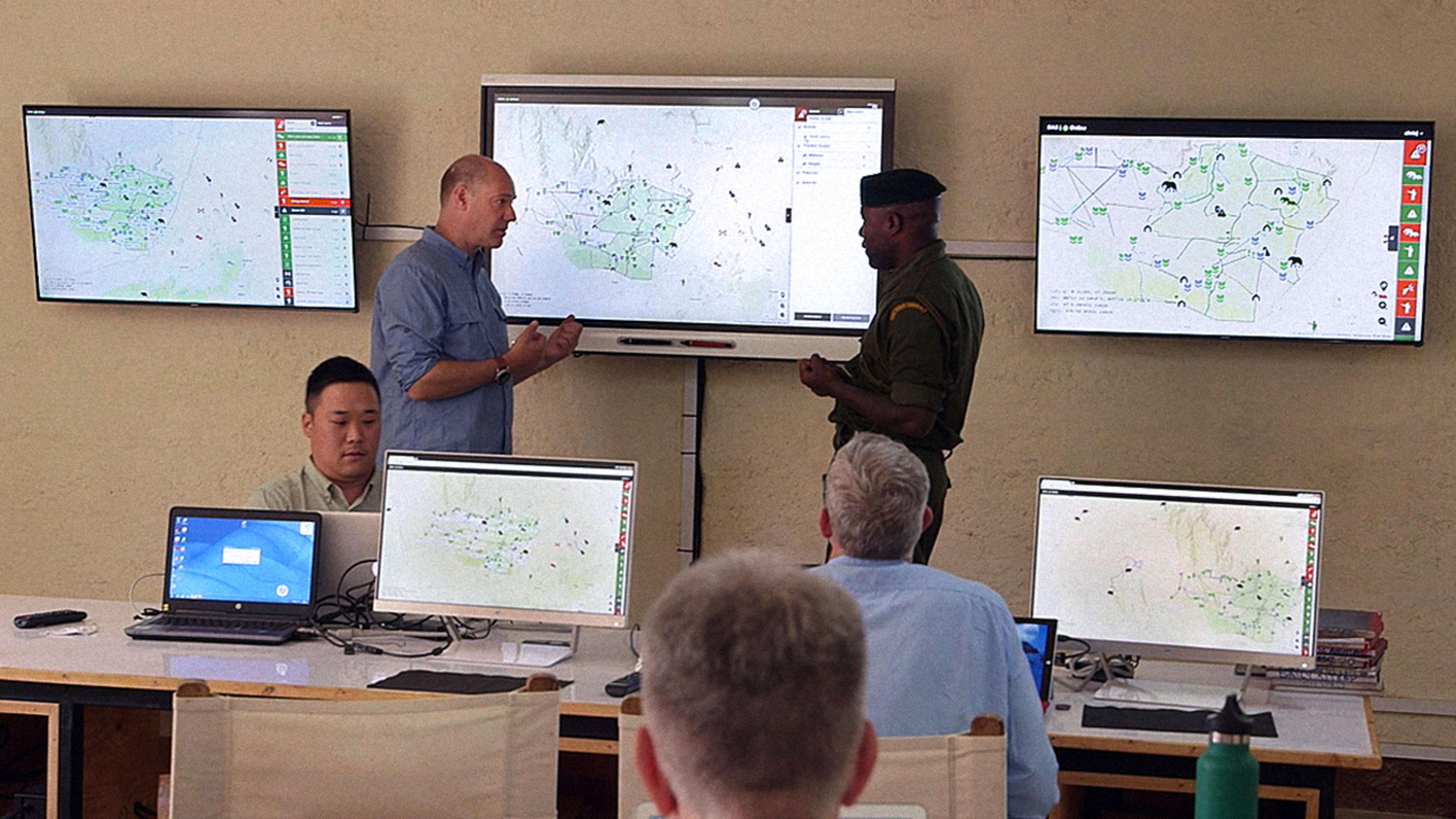

“They were trying to run their operation from that physical board,” says Ted Schmitt, principal business development manager for conservation technology at Vulcan, the Seattle-based philanthropic tech company founded by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen (who died on October 15), which partnered with the park to help it move to the company’s digital system, called EarthRanger, in April.

“They all know that poaching goes up during a full moon, for obvious reasons,” says Schmitt. “But what they don’t know, and they all expect, is that there are patterns like that latent in the data that they just can’t pull out. That’s the promise of machine learning…it’s going to let them be proactive.”

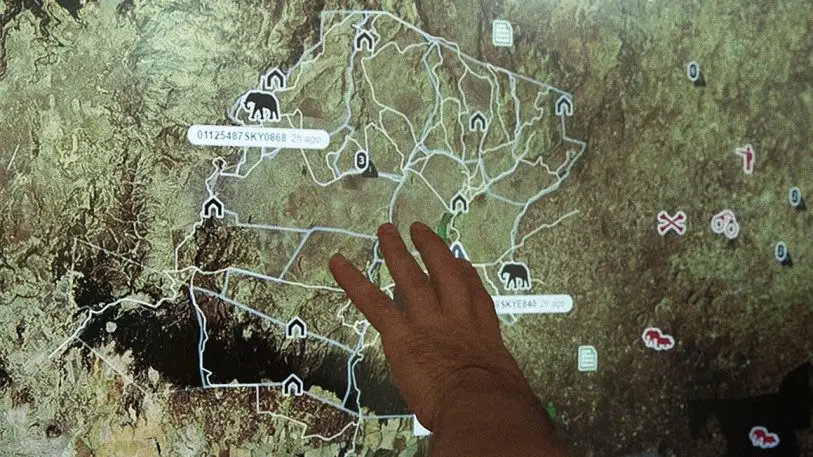

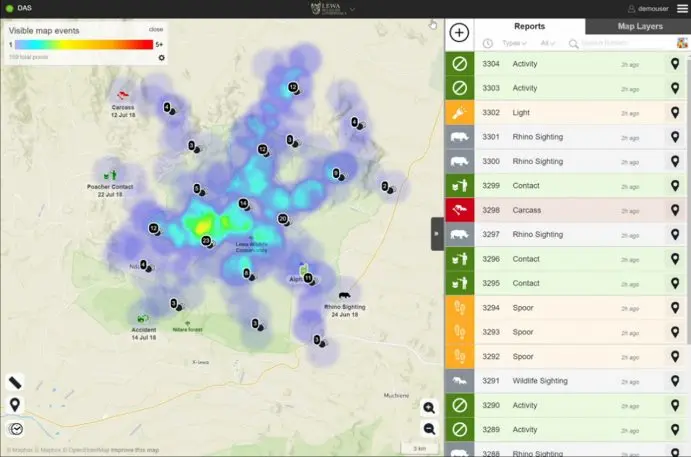

The machine learning is still in early stages of development, but some analytic tools are already in use. A new heat map feature, for example, first tested at Grumeti Game Reserve in Tanzania and Liwonde National Park in Malawi, showed that most incidents were happening near the borders of each park, so rangers could focus on those areas with the highest risk. A “time slider” feature lets park managers play back the locations of animals and rangers and better understand what time of day incidents are happening, where rangers are when they happen, and how well communication is happening between rangers.

Vulcan first launched the project after participating in the Great Elephant Census, a massive count of African elephants that found that populations dropped 30% between 2007 and 2014. Paul Allen and his team of technologists worked closely with park managers and conservation organizations to design a user-centered tool. The tech was first deployed in 2016, and will be at 18 locations in Africa by the end of 2018. It’s a long-term project, says Schmitt, and not something that is handed over to parks and forgotten. “This has happened in the past with a lot of technology that’s come into the space,” he says. “People come in, they’re going to save the day, they drop something in for three months, six months, and they declare victory and, and then they leave. And if you go back to the site, six months later, the tech isn’t being used anymore.”

Vulcan plans to soon publish metrics about how well the technology is helping protect the parks. “We are seeing a force multiplier effect happening with using very targeted data, real-time data, and getting that in the hands of people on the ground doing something about the bad activity,”says Art Min, vice president of impact at Vulcan. “The force multiplier lens is how we evaluate whether or not we should invest time or resources to solve some of these problems with machine learning.”

The project is now also part of the new Vulcan Machine Learning Center for Impact, which was created to help focus efforts on machine learning for public good. “For us, it was just a natural evolution of taking some existing projects, whether it’s technologies that we’re developing or our partners are, and then making a concerted effort to deploy them at a broader scale and in a collaborative way,” says Min. The new center will also help bring the tech community and nonprofits together around new projects, and will grow other existing projects including Skylight, which takes satellite images of the ocean and uses machine learning to identify illegal fishing, and the Allen Coral Atlas, which is using high-res images to map coral reefs, and will use machine learning to begin to predict when a reef might suffer from coral bleaching.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.