“For years, many women accepted it as a job hazard. Now, with raised consciousness and increased self-assurance, they are speaking out against the indignities of work-related sexual advances and intimidation, both verbal and physical.”

If you read this and thought it was the opener for an article written in the last year, you’d be wrong. It comes from a New York Times piece titled: “Women Begin To Speak Out Against Sexual Harassment” dated August 19, 1975.

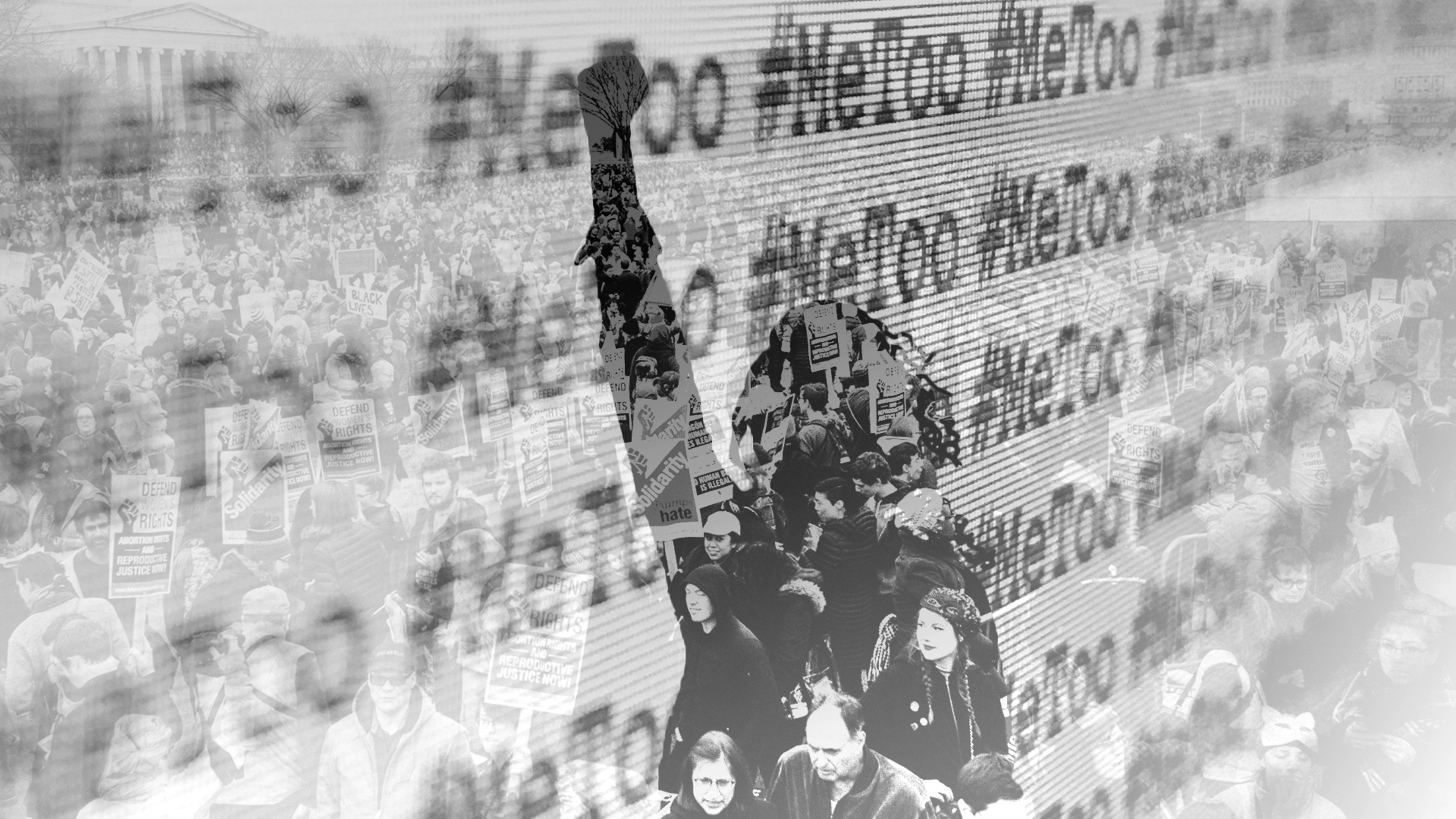

What happened in the intervening years between that story, the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements that gained traction in 2018, and the last year of remote work during COVID-19, is an evolution in attitudes about what constitutes appropriate behavior in the workplace. At times, it can feel like one-step-forward-three-steps-back. In part that’s because virtual interactions that occurred over the past 19 months didn’t prove to create a buffer from unwanted advances and inappropriate behavior, and also because it took nearly 50 years for the voices of those who had to soldier on while being harassed to gain enough momentum to topple (some) of the high-powered perpetrators of abuse.

While sexism and discrimination are as old as the human race, the very term “sexual harassment” was coined in the mid-’70s by Lin Farley, then director of the women’s section of Cornell University’s Human Affairs Program. “I kept thinking we’ve got to come up with a name,” she told the Times, “and the best I could come up with was sexual harassment of women on the job.” At that time, Cornell did a small survey of 155 women attending a workshop and found that 70% of them said they’d been harassed on the job, and of the 50% who said they reported it found that nothing was done. And at the time, there was no legal protection for the victims.

Not long afterward, in 1977, Ms. Magazine published a cover story called “Sexual Harassment on the Job and How to Stop It” to further raise awareness and give women the tools they needed to speak out.

Related: Would you know if your company had a sexual harassment problem?

The first sexual harassment case

It wasn’t until 1979 when Catharine MacKinnon, a Yale-educated attorney who had attended one of Lin Farley’s consciousness-raising events, published Sexual Harassment of Working Women that the U.S. judicial system began to see its way toward viewing sexual harassment as a form of discrimination.

In 1986, MacKinnon herself litigated on behalf of the plaintiff in Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson. Dorn writes, “In concluding that sexual harassment may violate sex discrimination laws, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was not limited to economic or tangible discrimination; rather, it found Congress’s intent was to “strike the entire spectrum of disparate treatment of men and women in employment.”

… and then, Anita Hill

Flash forward five years to 1991. That’s when Anita Hill testified about her boss, then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas (who was also head of the EEOC, the federal agency that fields claims of workplace sexual harassment) at his televised Senate confirmation hearing. Thomas denied Hill’s story and he was appointed to the Supreme Court anyway.

Related: Anita Hill gets real about sexism, race, and how far we still have to go

The rise of #MeToo

Although we often equate MeToo with a social media hashtag, the term was actually coined long before actress Alyssa Milano tweeted about it. Back in 2006, Tarana Burke coined the phrase as a way to give power back to women and girls of color who had survived sexual violence. Burke herself is a survivor and was working on a documentary about it when MeToo went viral on social channels.

Still many incidents go unreported and there are large swaths of the workforce unprotected. Title VII applies only to companies that employ at least 15 people. Individual states must decide whether to pass laws to cover the workers Title VII leaves out.

A previous report in Fast Company says:

Nineteen states have lowered the threshold for coverage below the federal 15-employee minimum, and 17 others and Washington, D.C., have scrapped it altogether. Alabama and Louisiana set a higher benchmark for state statutes at 20 employees, and Maryland and North Carolina have idiosyncratic claim-filing structures. The remaining 10 either don’t have statewide anti-discrimination laws at all or stick to Title VII’s 15-employee limit. In addition, some states have either mandated or officially “encourage” sexual harassment training, but predominantly for public-sector employees only.

Once again the world of work is at an inflection point in the wake of #MeToo and #TimesUp. As 2017 evolved into a year of reckoning for sexism, with nearly every month punctuated by multiple allegations of sexual harassment and abuse of power across industries from tech to entertainment.

It’s no surprise then, that there has been a significant increase in the number of women (and men) reporting incidents, according to data from anonymous employee polls on Comparably. However, their experiences and voices are the necessary through line at all points of this evolution. And they are being encouraged.

Concerned that many victims of harassment still fear being fired or blackballed, advocacy group Women in Film set up a hotline to provide them with support or connect them to an attorney. Time’s Up is the legal defense fund created by some 300 actors and female executives, agents, writers, directors, and producers and aimed at assisting underprivileged women dealing with harassment in workplaces like factories and hospitals. Time magazine’s Person of the Year in 2017 was a group of “Silence Breakers,” the women who had the courage to speak out.

As Meher Tatna, the current president of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, put it, “The story has to be continued until there’s no need for it anymore.”

The rise of virtual harassment

The pandemic sent many knowledge workers home to work in relative safety from COVID-19. However, virtual meetings would prove to be just as fraught as conference rooms and other physical workspaces. A recent Project Include survey revealed that over the past year, 25% of respondents experienced an uptick in gender-based harassment particularly among those who identify as Black, Asian, Latinx, Indigenous, and female or nonbinary.

Another report from Washington-D.C.-based nonprofit The Purple Campaign, nearly matched those findings with one-quarter of employees polled reporting an increase in gender-based harassment during the past year.

There are myriad reasons for the continuance of inappropriate behavior. In a recent Fast Company article, experts observed that it’s actually easier to harass others when no other coworkers are close by to overhear. Sitting behind a screen using chat or direct messaging often emboldens bad actors, too, especially as the boundaries have blurred between work and home over the past 19 months, and people are more casual in conversation. (Lest we forget, CNN’s chief legal analyst and staff writer for The New Yorker Jeffrey Toobin made headlines after being caught masturbating while on a Zoom call with his colleagues.)

“People will say and type things that they would never say out loud and do if they were coming into a physical work space,” Broderick C. Dunn, a partner at Cook Craig & Francuzenko, PLLC, told Fast Company. Unfortunately, he said, people still need to be reminded of the need to “show the same restraint when working from home as they do in the office.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.