Ride the elevator up to the eighth floor of a loft-like office building in the heart of Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood, and you’ll find a thriving education technology startup called Amplify on track to book $125 million in 2018 revenue. In one room, a team develops a computer science challenge involving coral reefs in Hawaii. In another, a product manager demos a reading lesson involving a teen rebel in a dystopian graphic novel. Brad Powell, managing director for investments at Emerson Collective, the Laurene Powell Jobs-founded philanthropic organization that is Amplify’s majority owner, credits the company with doing an “outstanding” job as it has grown to serve 4 million students.

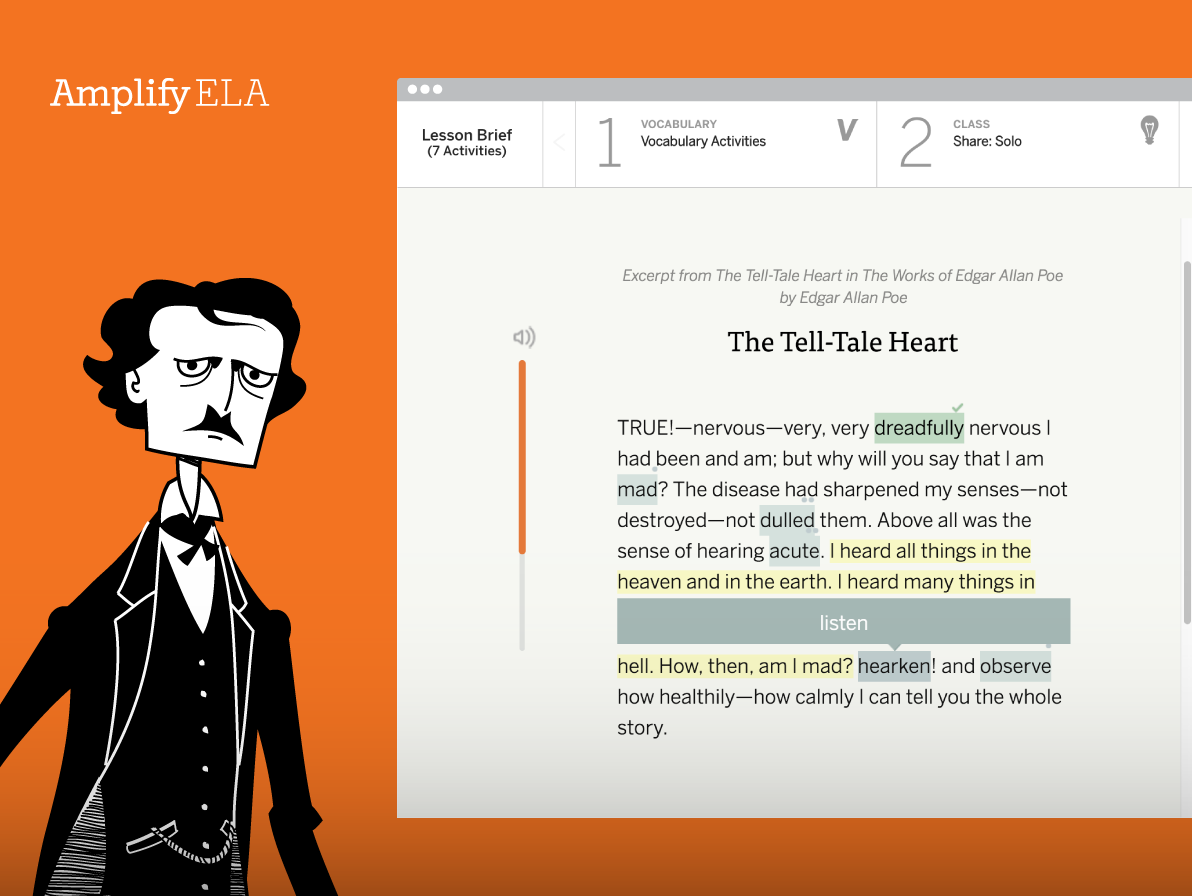

Today, Amplify CEO Larry Berger would like to put that chapter behind him. “Big companies can sometimes have grand ideas about how much can be accomplished at one time, and so I think we stretched into a lot of areas that didn’t stay close to our core expertise around making great stuff for teachers,” he says during an interview at his sparsely decorated, windowless office. In the three years since he brokered a spinout deal with Emerson, giving him a chance to restart the company he cofounded, Berger has moved on: “The big news story is science, reading, and math,” he says, referring to Amplify’s signature curriculum offerings.

“Explore, play”

Many customers have moved on as well. Free of the News Corp umbrella, Amplify has been able to win over schools in all 50 states. Its new science offering, which launched in spring 2017 and spans kindergarten through eighth grade, has been adopted by major school districts including Chicago, Denver, and New York City, as well as the KIPP charter network. Already, 950,000 students are using the program.

One afternoon in August, I join Steven Zavari, general manager for Amplify Science, to view the simulations that the company developed to accompany lessons created in partnership with the Lawrence Hall of Science at the University of California, Berkeley. In each lesson, students inhabit the role of scientist or engineer. To study genetics, Zavari mates spiders over a series of generations and observes how traits like venom pass from parent to offspring. To study natural selection, he sets climate variables for a miniature ecosystem, and we watch as a fictional animal species attempts to survive.

“You cannot break it,” Zavari says, as we try another climate scenario. “Explore, play.”

[Animation: courtesy of Amplify]The Amplify Science lessons map to the Next Generation Science Standards, a 26-state effort launched in the wake of the Common Core Standards, which address English language arts and math. For teachers who think of science education as oriented around the memorization of facts, the Next Generation standards are a dramatic departure. They instead focus on natural phenomena and the application of concepts to real-world problems.

“This is a huge shift,” says Katie Ramsey, science coordinator for Grand Island Public Schools in Nebraska. Last year, she oversaw her district’s adoption of Amplify Science, after piloting the curriculum alongside two competing products. “This isn’t about students being able to regurgitate a fact that they could just Google. This is about students spending more time in gathering evidence and evaluating evidence and communicating their reasoning to support or refute a claim.”

So far, Ramsey says, teachers have been happy with the Amplify lessons. “It’s amazing how we’ve seen our students grow in their ability to think in terms of finding patterns or designing systems or cause-effect. The littlest, from kindergarten up, are able to do this.” During a visit to a third-grade classroom, she recalls, she made the mistake of saying to one student, “You’re helping the wildlife biologists out.” He immediately corrected her: “No, we are the wildlife biologists.”

But developing Amplify Science to this high bar of quality has not come fast or cheap. “Lawrence Hall of Science has been the author on this, really writing and elaborately testing,” says Berger. “That was the big thing in which we were simpatico. They just field trial, and field trial, and field trial until they feel they have something right, which is why it’s six-and-a-half years later that we actually shipped the product.”

From promise to mounting frustration

Emerson Collective has been understanding of such timelines; News Corp, on the other hand, was less so. Interviews with former executives who were involved with Amplify during its News Corp years paint a picture of never-ending product delays, squabbles over resources, and mounting frustration. At the outset, though, employees looked on the $360 million deal with a sense of promise.

“News Corp seemed like a fresh slate. It wasn’t a big pre-existing [education] company that was going to layer on their vision,” says Li Reilly, Amplify’s former deputy general counsel.

Indeed, News Corp had no prior education assets or experience. Then chairman and CEO Rupert Murdoch had recently ramped up his education philanthropy, and had become enamored with the idea of combining his business and charitable interests. Around the same time, the education reform movement was championing the idea of applying business principles and practices, like data analytics, to schools; why not take the next step, Murdoch mused, and use a business venture to achieve better student outcomes?

The deal to acquire Amplify came together quickly—no bankers were involved. Berger had received an unsolicited offer from Pearson during a breakfast meeting, and brought the matter to his board of directors. (Pearson declined to comment.) By happenstance, around the same time, one of Berger’s contacts in the education reform world asked him to weigh in on Murdoch’s still-murky plans. Suddenly, the company had a bidding war on its hands, as Berger went from adviser to target. In the end, News Corp “radically” overpaid what was then known as Wireless Generation, according to a source familiar with the $360 million deal, which gave News Corp a 90% stake. Berger pocketed $40 million, including performance incentives, and agreed to stay on as head of curriculum.

The catch: Amplify hadn’t previously developed curriculum. It had licensed curriculum, and built assessment tools for teachers. Its primary product, an early reading assessment, had been successfully sold to a number of states. But News Corp wanted to outgun education’s biggest publishers, including Pearson and Houghton Mifflin, by beating them to the punch on digital curricula in reading, math, and science. So Berger and his team began to staff up, hiring designers and engineers by the dozen. At the outset, at least, money was no object.

Murdoch’s initial idea: Buy a billion iPads

Soon, News Corp added a second dimension to its ambitious education plans. Berger’s curriculum products were being designed to live on tablet computers—a device that most schools did not yet own. In true mogul fashion, Murdoch initially floated the idea of buying a billion iPads, according to one source. But the company eventually realized that Apple, with its stringent app-based operating system, would not offer the type of access and flexibility that Amplify’s curriculum would likely require. Instead, Amplify committed to making a tablet of its own.

While the new hardware division toiled in Manhattan, Berger remained in Brooklyn with his curriculum team. At the time, most digital lessons on the market were glorified worksheets, converted from paper to screen. Berger, in contrast, wanted to “do it right,” says a source, through engaging formats and best-in-class content. For example, his team put works by author Roald Dahl high on their wishlist. Negotiating the rights took months. They also sought out talent like actor Chadwick Boseman, who read an excerpt from Frederick Douglass’s autobiography for the English language arts curriculum.

It didn’t take long for tensions to emerge. Murdoch had hired Joel Klein, a former prosecutor who had served as chancellor of the New York City Department of Education, to oversee his education subsidiary, and Klein managed his direct reports with a litigator’s love for conflict. “We had a lot of smart people, but lots of crazy egos,” recalls one source. Rather than coordinating their efforts, curriculum and tablet divisions began to compete. When one leader wanted to use another’s research staff, there was a squabble over the shared resources.

Klein, who says he is “thrilled, though not surprised, that Amplify is succeeding,” disputes this characterization of his management. “My style . . . is to empower, support, and hold people accountable,” he says. “At Amplify, as at any startup, there were some disagreements about early-stage strategy and tactics, as well as over-resource allocation.”

The tensions came to a head after News Corp’s June 2013 separation from 21st Century Fox, precipitated in part by the phone-hacking scandal that had embroiled the media giant in the U.K. Amplify, once a bit player in a $75 billion corporate behemoth, suddenly represented a meaningful portion of News Corp’s bottom line. So it did not look good when Amplify had to halt its first major product rollout that October. Guilford County Public Schools in North Carolina had paid $16.8 million for 15,000 Amplify tablets; less than a month into the school year, 10% of the devices had cracked screens and one charger had melted, raising safety concerns. Guilford returned the devices for repairs, and Amplify was forced to give the district $856,750 to compensate for staff time and training costs.

Despite the negative press, the stunted launch was viewed internally as a fixable sideshow. It only overshadowed the curriculum, says one source, because there was no curriculum to speak of. Even after three years of investment and development, the curriculum’s rollout timeline remained unclear.

By 2015, News Corp was looking to exit the education business altogether. It was a delicate matter: News Corp did not want to abandon the schools that Amplify was serving, and risk a media backlash. Berger, once again using his strong connections within the education reform community, helped broker the sale of Amplify’s curriculum assets to Emerson Collective, securing a minority stake for himself and other managers. Emerson paid just a small fraction of News Corp’s initial investment, according to a source close to the deal. In the process, News Corp shut down Amplify’s tablet operations and laid off more than 500 employees.

“They had a lot of high-quality assets that may not have made it to market without finding the right buyer,” says Powell. “The results are really starting to speak for themselves.”

Breaking the $100 million mark

Today, Amplify is operating with a greater sense of focus—while reaping the benefits of the time and money that News Corp provided. Amplify booked $59 million in revenue in 2016, its first year of independence, and $74 million in 2017. This year, it’s on track to book $125 million, making it one of the few education startups to break the $100 million mark.

“We had a chance to buy it back knowing that it was sort of one year from being market-ready, and that as a smaller company we could make it work,” says Berger. “Suddenly we had to be lean and focused and make sure that everything we were doing was tied to a really clear thesis about what teachers want to use in the classroom.”

Amplify’s reboot has coincided with the rise of personalized learning, a pedagogical approach that seeks to tailor lessons to each student’s level of mastery and learning preferences. But while other companies have raced to “personalize” their offerings, Berger has stayed the course on Amplify’s more traditional approach. “I don’t think what teachers want is to put their feet up while kids are each on a private learning journey,” he says. “We don’t necessarily believe in what I’ve called the ‘engineering model’ of personalized learning, which is each kid on some optimized path for exactly who they are, and exactly where they are starting. Instead, what are the things you can do to push kids who are advanced a little bit further, scaffold kids who are behind, so they can have a point of entry, but then work together as a class, as a community of humans learning something together?”

In practical terms, this approach makes Amplify accessible to schools without the resources for 1-1 student-to-device ratios. Plus, it gives the company the ability to provide schools with printed versions of its curriculum, ensuring that all teachers buy in, regardless of their comfort with technology or personalization strategies.

Features like that can sometimes make a bigger difference than “all the bells and whistles that Amplify built into their product,” says Michael Horn, cofounder of the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation and author of two books on disruption in education. “It’s a question of really understanding the customer deeply.” Despite the company’s recent momentum, he says, “It remains to be seen whether Amplify has really cracked that nut.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.