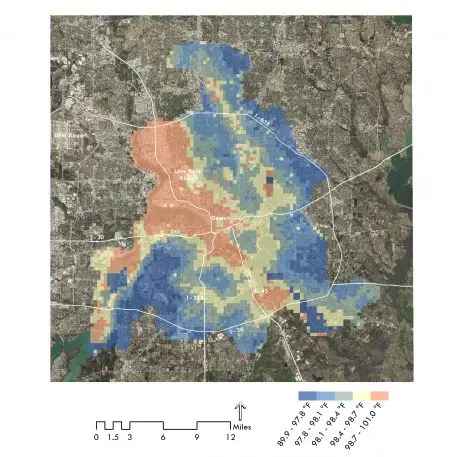

On a hot day in Dallas, when the temperature soars above 100 degrees, it might be as much as 10 degrees hotter in some neighborhoods. A new project mapped which parts of the city are hit hardest by the urban heat island effect–the fact that pavement and buildings and human activities make cities hot–and then started planting trees to help cool one neighborhood down.

In a low-income neighborhood in Oak Cliff, a midcentury suburb where the tree canopy–the layer of branches and leaves overhead–barely exists in some areas, the city is going to plant more than 1,000 trees.

“If you were to drive through this neighborhood and drive through an affluent neighborhood you would see here what you see in a lot of American cities, which is that poorer neighborhoods tend to have less vegetation–fewer trees, fewer parks, less open space,” says Laura Huffman, the Texas director for The Nature Conservancy, which partnered with the Trust for Public Land and the local nonprofit Texas Trees Foundation on the project. “Basically the vision we have, not just for this neighborhood, but for the entire city, is to re-vegetate.”

In a study with Georgia Tech, Texas Tree Foundation looked at summer temperatures throughout the city, finding that the hottest areas averaged 100 degrees. Planting trees and adding other greenery, they found, could help cool some areas as much as 15 degrees on hot days. Beyond providing shade, trees help cool the air as water evaporates from leaves. The study found that planting trees was three times more effective than other strategies for cooling the city of Dallas.

“If we had unlimited resources, we would plant trees everywhere, but this study allowed us to pinpoint those neighborhoods where we could do the maximum amount of good with the resources that we have,” says Matt Grubisich, director of operations and urban forestry for the Texas Trees Foundation.

Volunteers helped plant 500 trees last winter and spring, and will plant hundreds more this fall. The trees come with multiple benefits. Keeping the neighborhood cooler can help reduce ground-level ozone pollution. The leaves can also absorb pollution, helping reduce asthma attacks and other health problems. Having greenery nearby can also make people happier. Trees also slow down traffic, reduce crime, and can make people feel seven years younger. Planted en masse, they can also be part of helping cities meet goals for reducing their carbon footprints.

As cities get hotter–by 2100, summer in New York City could feel like Juarez, Mexico, does now–more cities are starting to plant trees and other greenery to mitigate heat. Madrid, for example, is planting greenery on walls and roofs and turning vacant lots into parks. Others may begin to use the precise mapping used in Dallas. “These are very replicable strategies,” says Huffman.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.