At a time when mainstream corporations and CEOs are increasingly vocal about politics–from United and other airlines denouncing family separations, to Delta cutting ties with the NRA after the Parkland shooting, and companies like Dow Chemical and even Exxon urging Trump to keep the U.S. in the Paris climate agreement–Ben & Jerry’s may still be the only company with an in-house “activism manager” pushing consumers to become more politically involved as they enjoy their pint of Chunky Monkey.

The company is currently supporting the Poor People’s Campaign, a revival of an economic justice campaign originally launched by Martin Luther King Jr. and cut short by his assassination. The current grassroots campaign, which ramped up with 40 days of direct action earlier this year, aims to organize poor people around fighting what King called the “triple evils” of racism, poverty, and military spending, along with ecological destruction. Ben & Jerry’s used social media and signage in its ice-cream shops to urge consumers to sign up to support the campaign, and donated part of the proceeds from a limited-edition ice-cream flavor (“One Sweet World”), which it also served to activists.

The company’s support for this particular campaign, and a Ben & Jerry’s post talking about the fact that some leaders have exploited racial and social divisions to “let the ultra-wealthy . . . accumulate more wealth and power,” is a little bolder than some other corporate activism. “These days, it’s not especially controversial to be in favor of marriage equality or to be against overt racism,” says Jerry Davis, associate dean for business and impact at Michigan Ross School of Business, adding, “By addressing specific issues of economic inequality, I do see this as going beyond what we have previously seen from big business.”

The hippie-founded company, of course, is known for a history of activism. “There was a moment about three years into running Ben & Jerry’s that [cofounder Ben Cohen] sort of had this epiphany that he had become everything he loathed in society–a businessman,” says Miller. “The cofounders actually came close to selling the company, and Ben had a friend and mentor that said, ‘Look, if you don’t like the way the business world operates, change the way you run your business.’ That was sort of the moment in which Ben thought, ‘Right, I can align my values with the way I run the business.'”

Part of that meant creating one of the first triple-bottom-line businesses–making sourcing decisions like buying brownies from a bakery that hires people who were homeless or recently out of prison, or buying coffee from a rural cooperative in Mexico. It also meant activism, and donating money to a campaign to redirect some national defense budget funds to peace-promoting activities, for example, or asking customers in ice-cream shops to sign postcards in support of a campaign for children’s basic needs. When financial pressures led the founders to sell to Unilever in 2000–a controversial step–the deal included creating an independent board to keep its social mission intact. (Cohen continues to make ice cream under the brand Ben’s Best, and continues to support causes, including the Bernie Sanders campaign with a flavor called Bernie’s Yearning). The company struggled after the sale, but the board eventually succeeded in making the social mission strong again. The company has also grown since the acquisition, and is now sold in around 35 countries. In 2012, the company was certified as a B Corp, an independent certification that evaluates socially responsible businesses that was, in part, inspired by the Ben & Jerry’s sale.

The new activism manager position was created about five years ago as Ben Cohen phased out of day-to-day operations and as the company started to think about its activism as “campaigns.” Miller was hired because of his campaigning experience, and began to shift to working more closely with grassroots movements rather than creating campaigns internally. Each of the campaigns, like one leading up to the Paris climate conference that gathered more than half a million signatures in support of a transition to 100% renewable electricity, is created in partnership with nonprofits that are experts in an area (in the case of Paris, it was the climate nonprofit 350.org).

“Ben & Jerry’s has a huge megaphone and unlike some other companies, they’re not afraid to use it,” says Jamie Henn, cofounder of 350.org. “They help us reach new audiences, raise awareness about important campaigns, and put pressure on key decision makers.” The nonprofit worked with Ben & Jerry’s on the People’s Climate March and other events leading up to the Paris summit, and a campaign in Australia encouraging local governments to divest from coal.

“We don’t accept any corporate donations and are careful about the companies we work with because it’s essential for us to maintain our independence,” says Henn. “What makes Ben & Jerry’s unique is the time and energy they put into connecting with grassroots groups. They’re not looking to just write a check: They want to understand the issue, get engaged with groups on the ground, and support the work that really matters. We’ve also worked with Patagonia, North Face, and Clif Bar, who all take a similar approach.”

Unlike a cause marketing campaign that might try to build brand equity by supporting an issue that consumers already care about (or that is noncontroversial, such as research for breast cancer), Ben & Jerry’s says that it bases each campaign on its own concerns, not marketing research.

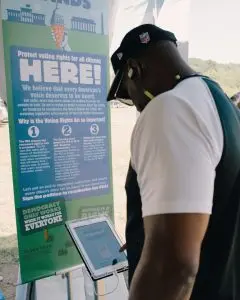

Miller says that working for the ice-cream brand is an opportunity to reach beyond an audience that’s already taking action, like the sort of audience he worked with at Greenpeace. “Our customer base likes us because they really dig Chunky Monkey or Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough,” he says. “So we have this opportunity to play a bit of bait and switch. To preach not just to the choir but to a broader mainstream audience.” (The ice cream itself becomes a part of the work, from “Empower Mint” to support a voting rights campaign.)

That’s unlikely to mean converting a climate skeptic to a climate activist, he says. But the company does hope to reach millennial consumers who share the same values but may not yet be politically active. “They are people who care about the world,” he says. “They have strong values. They have lost faith broadly in the ability of the political system to make that change and don’t really know how to get involved in these issues or how to become part of making change in the world. So we see our role as really providing an on-ramp or being a conduit through which these aspiring activists can join others in taking action.”

The campaigns aren’t always successful; one effort to get national mandatory labeling for genetically engineered ingredients on food packaging failed when Obama signed a law preempting this type of labeling. (Most scientists would probably say GMO labeling isn’t necessary because they believe GMO food is safe.) Another current campaign, a Florida ballot initiative to give people convicted of a felony the right to vote, may also be challenging. But others have worked, like a campaign to stop dredging of the Great Barrier Reef and dumping the dredging waste in the marine park. In a partnership with World Wildlife Fund, Ben & Jerry’s set off on a road tour of Australia, handing out free ice cream and telling customers about the problem; after politicians called for boycotts of Ben & Jerry’s, the government finally banned dumping waste in the reef.

It’s the type of work that may become more common in other companies as well, beyond a handful of others doing it now–like Patagonia, which is pushing customers to fight for public lands reduced by the Trump administration, and which joined others to sue Trump for making the changes.

More general corporate activism is also likely to grow, says Davis, often moving in the other direction, with consumers pushing companies to act. “I think because of social media, it is easier for customers to mobilize if they think that a company’s misbehaving or if they think a company can be nudged in a different direction,” he says. “It’s a lot easier to join together with others and form a sort of virtual social movement.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.