When Apple’s iPhone App Store opened for business 10 years ago today, alongside the release of the iPhone 3G, it was a revelation. Suddenly, having a centralized way to find, purchase, download, and update applications didn’t just seem like a smart idea, but a mandatory one for any company in the software platform business.

It wasn’t long before app store mania took hold, as other tech companies tried to recreate Apple’s business model, even when doing so didn’t make much sense. Soon enough, app stores weren’t just the domain of smartphones. They also started popping up on desktop computers, within web browsers, and even inside social networks. Unsurprisingly, few of these efforts have survived.

As the iOS App Store turns 10 years old, let’s look back at the long list of imitators that flopped—or ar least didn’t experience anything like the instant, epoch-shifting success of Apple’s original software storefront.

Blackberry App World

Launched: March 2009

What it is: A way to find, download, and purchase apps for Blackberry phones, announced when it became clear that any smartphone platform without an app marketplace would be a nonstarter. (In 2013, Blackberry changed the name to “Blackberry World” to coincide with the launch of its Blackberry 10 operating system.)

What happened: While the idea of an app store for Blackberry phones made sense, the platform had deeper problems that a storefront alone couldn’t solve. Despite some early success for App World developers, Blackberry’s clunky operating system and hardware couldn’t keep up with the iPhone and Android, and Blackberry 10 arrived too late to gain any momentum. Although Blackberry claimed that its store had 120,000 apps by mid-2013, it turned out that more than a third of them came from a single developer that had perfected the art of shovelware.

Current status: The last Blackberry 10 phones arrived in 2015, but Blackberry says it will support them through the end of next year. Until then, Blackberry World lingers on in a vegetative state.

See also: The Windows Phone Marketplace, which never gained enough developer traction to give Microsoft a chance in the smartphone wars.

Chrome Web Store

Launch date: December 2010

What it was: A way to discover–and, in some cases, purchase–web-based apps and games that ran inside Google’s Chrome browser. The goal was to give Google a platform-within-a-platform on Windows and Mac, but also to help establish an app ecosystem for Chrome OS.

What happened: Despite several attempts by Google to encourage app-like experiences using web technologies, most Chrome Web Store apps were just bookmarks to existing websites. Users didn’t need an app store for that.

Current status: Although the Chrome Web Store still exists for browser extensions and themes, Google shut down the apps section on Windows, Mac, and Linux last year. And while those apps are still available on Chrome OS, their fate seems uncertain now that Google has brought the Android-based Google Play Store to Chromebooks.

See also: Firefox Marketplace, Mozilla’s similar–but more open–attempt at a web-based app store. It fizzled out alongside Firefox OS, and officially shut down in March.

Intel AppUp

Launched: January 2010

What it was: Intel’s attempt to establish an app store within Windows–particularly on netbooks and ultrabooks–before Microsoft got around to doing so. Laptop makers were encouraged to preinstall AppUp in exchange for a cut of store revenues; Asus and Acer even launched their own branded versions of the store. Eventually, Intel hoped AppUp would run on more than just PCs, including devices running on a nascent mobile operating system called MeeGo.

What happened: Laptop perused the store in the fall of 2010 and found it be “sparsely stocked,” though it did land Angry Birds the following year. And while the store had tens of thousands of registered developers, Intel seemed to recognize that getting consumers to care about a third-party app storefront was an uphill battle. In an interview with PC Mag in 2011, Intel’s Peter Biddle cheerfully called AppUp “the world’s largest app store that nobody’s ever heard of.”

Current status: Intel shut down AppUp in 2014, two years after Microsoft released Windows 8 with its own app store. Still, the chipmaker didn’t directly acknowledge the Windows Store as a reason for AppUp’s demise, saying only that it wanted to focus on “the needs of enterprise and business users.”

Wholesale Applications Community

Announced: February 2010

What it was: A joint effort by wireless carriers–including AT&T, Sprint, Verizon, and T-Mobile parent Deutsche Telekom–to create their own app store that worked on any phone, regardless of operating system, thereby allowing them to cash in on the app craze. Instead of creating native apps, the group wanted to push apps based on open web standards.

What happened: Andy Rubin, then Google’s head of Android, immediately dumped cold water on the idea, and Apple had little incentive to participate with the iOS App Store already in full swing. Over the next two years, the project languished as carriers had trouble agreeing on a common distribution model, and the group dissolved in 2012 without having launched anything.

Current status: Although the Wholesale Applications Community dream never came to life, you can still visit a website extolling the group’s values and approach.

Facebook App Center

Launched: June 2012

What it was: Not exactly an app store, but a hub for finding iOS apps, Android apps, and websites that played nicely with Facebook. It certainly looked like an app store, though, with personalized recommendations and ratings for each app. The App Center arrived shortly after Facebook expanded its Open Graph, which allowed apps to automatically share information about users’ activity with friends. Apps that supported this Facebook feature, such as Spotify, were among the App Center’s most-promoted apps.

What happened: In 2014, Facebook scaled back the App Center to include only games. Although the company didn’t explain its reasoning, users probably weren’t interested in browsing for apps based on whether or not they would share data with Facebook. And over time, Facebook has rolled back many of the data-sharing capabilities it was pushing for third-party apps back in 2012.

Current status: Although Facebook has gotten out of the app curation business, its game portal is still around.

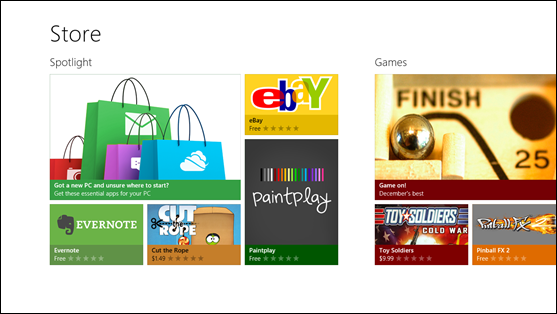

The Windows Store

Launched: October 2012

What it was: A centralized way to find, purchase, and download Windows apps, particularly those that were optimized for touch screens in Windows 8 and Windows RT using the interface originally known as “Metro.” At launch, plain old Windows desktop software was not allowed into the store.

What happened: The Windows Store’s fate is entwined with that of Windows 8 itself. Many users didn’t appreciate Microsoft’s pivot to a touch-centric interface, and were rightly opposed to abandoning desktop software for a limited and less capable selection of apps. Although Microsoft attracted some big names like Netflix and Evernote, the Windows Store never rivaled the breadth of the iOS App Store and Google Play Store.

Current status: As Microsoft has refocused on the desktop, its Windows storefront–now called the Microsoft Store–has turned into a hub for all kinds of programs, including ones that aren’t designed around touch screens. (Programmers and Linux enthusiasts can even use the store to download the Ubuntu Terminal.) When viewed as an optional benefit for Windows users, the store isn’t a failure, but Microsoft’s attempts at building versions of Windows that only run Store apps have yet to take off.

Skype App Directory

Launched: August 2011

What it was: A centralized location for apps built on Skype’s developer tools, complete with ratings, reviews, and screenshots. Example apps included call recording software, a way to look up and join conference calls from your calendar, and a screen-sharing tool.

What happened: The Skype App Directory might’ve been inspired by mobile apps, but it was also a victim of them. In 2013, Microsoft discontinued Skype’s desktop API to focus more on mobile development, and shut down the App Directory that year.

Current status: Four years after shutting down the App Directory, Microsoft launched a developer preview for Skype add-ins, letting users add GIFs, polls, and information from third-party apps to their conversations. But for now, there are less than 20 add-ins available, and no clear need for an app store to manage them.

See also: Office add-ins for an example of Microsoft successfully extending its software with an app store.

Mac App Store

Launched: January 2011

What it is: A central source for browsing, buying, and downloading MacOS apps, vetted by Apple. “The App Store revolutionized mobile apps,” Apple CEO Steve Jobs said at the time. “We hope to do the same for PC apps with the Mac App Store by making finding and buying PC apps easy and fun.”

What happened: While the Mac App Store isn’t exactly a failure, it’s also no revolution. Developers have complained for years about how the store limits what their apps can do, doesn’t support certain business models (such as paid upgrades), encourages a race to the bottom in pricing, and makes them less money than they expected. A survey last year found that more than half of developers make most of their money from outside the Mac App Store, and more than two-thirds said Apple’s 30% revenue cut isn’t worth what developers get in return.

Current status: Apple seems to have realized that the Mac App Store needs a boost. At this year’s Worldwide Developers Conference, the company announced a design overhaul for the Mac App Store similar to the one that launched on iOS last year, with video previews, larger image thumbnails, and lots of editorial commentary. Apple is making improvements to sandboxing, which limits how apps can access system resources and user data. Some app makers that had pulled software from the Mac App Store in previous years now plan to support it again, and some high-profile programs such as Adobe Lightroom CC and Microsoft Office are headed to the store as well. Perhaps more importantly, Apple is now building a framework that will allow developers to easily write apps across both iOS and MacOS.

Lessons learned

Back in 2008, the iOS App Store was an instant hit because it served a clear need for users, who were demanding more slick apps like the Apple ones that came pre-loaded on their iPhones. The web-based apps that Apple had pushed during the iPhone’s first year just weren’t good enough. Three months later, Google’s Android Market–now known as Google Play–took off for similar reasons.

Other than the Android Market, most of the App Store’s imitators were trying to graft an app store onto platforms where software and usage patterns were already well-established. While it was easy to look at the Apple’s success and assume that same model would work everywhere, in reality the App Store was the kind of revolution that only happens once in a lifetime–much like the iPhone itself.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.