Itsuko Noto lives in Japan, which means it takes her a minimum of 12 hours to fly to Las Vegas. But at least twice a year she grabs her passport and makes the journey to Sin City for intensive Cirque du Soleil immersion–two shows a night, 14 total per week.

Although she sees nearly all of the company’s seven different Vegas shows (except Criss Angel’s “Mindfreak Live”), as well as many of its other shows around the U.S., Asia, and Europe, “O” is her mainstay. First opened in Vegas in 1998, “O” is Cirque’s famous water show, probably its most ambitious, given its clever and beautiful incorporation of a 1.5 million-gallon swimming pool that, at certain points, seems to magically disappear.

Every night she’s in Vegas, Noto makes her way over to the grand 1,800-seat theater at the Bellagio for “O’s” late show. All told, she takes in 10 “O” performances a week, and over the course of her career as an all-star Cirque fan, she’s seen it well over 100 times.

“It touches my deepest emotion,” Noto tells me by email. “I feel the tears welling up at the end of the show every single time.”

For the folks at Cirque du Soleil’s Montreal headquarters, there’s something powerful and intriguing in Noto’s experience, in the way she expresses the emotions “O” raises in her. And more important, there’s something in that experience they thought they could—and should—measure and quantify, because emotional experiences can guide their business decisions for years to come.

“We have some [fans] who keep coming back, 30 to 40 times, mostly various shows, but the fact that [Noto] would come back and see the very same show [more than] 100 times, always “O,” we found that fascinating,” says Marie-Hélène Lagacé, Cirque’s head of public relations. “What is it that you feel when you come see the show that makes you want to feel it again and again and again and again?”

Searching for awe

Although I can’t play in Noto’s league, I’m still a self-professed Cirque nerd. I’ve seen at least 40 Cirque performances over the years, and 14 years ago, I worked briefly as an usher on “Alegria,” one of the company’s most beloved traveling shows.

But never before had my experience of seeing a Cirque show been like the one I had at “O” in late April as the ground-breaking company was celebrating its 35th anniversary.

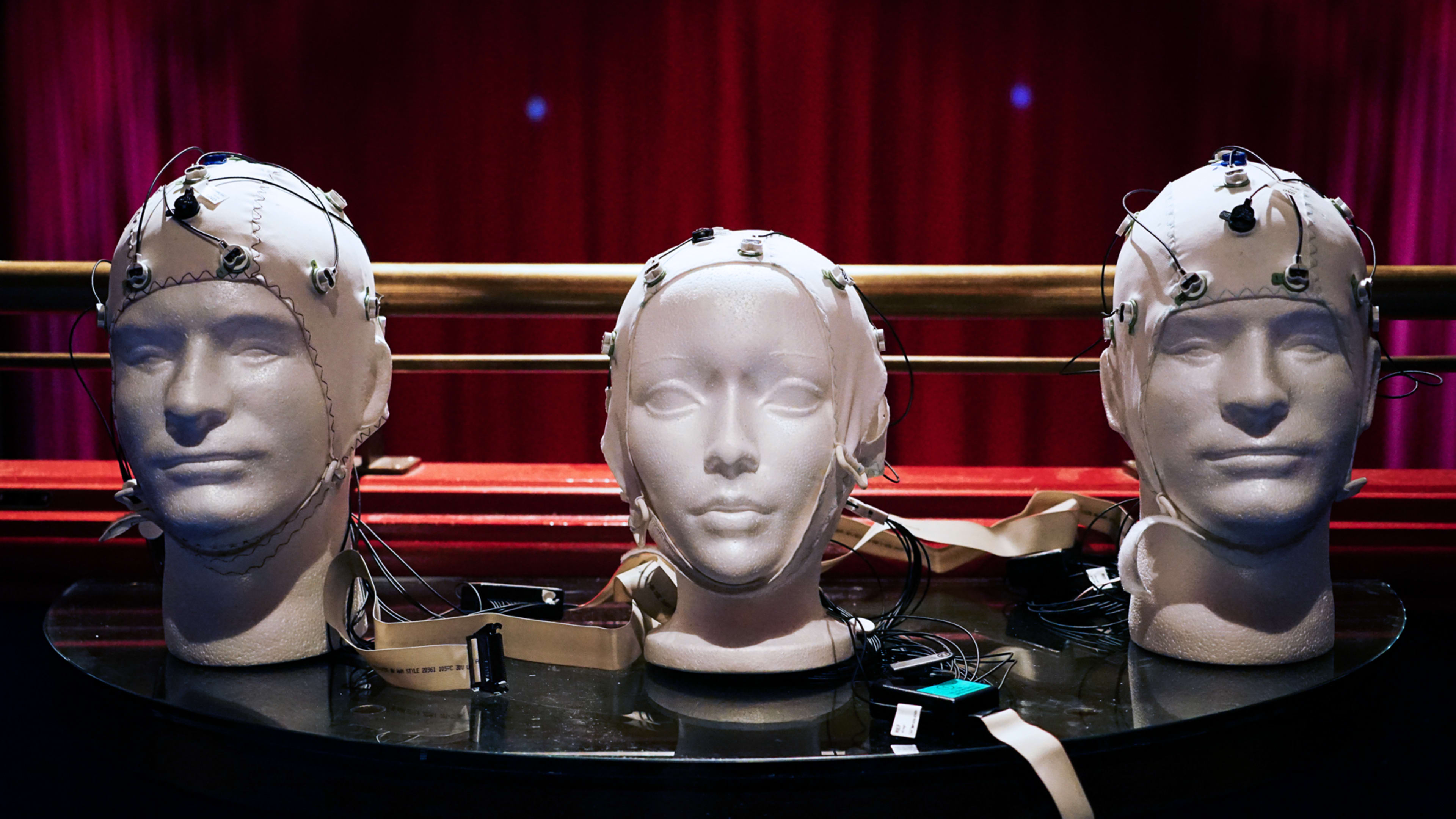

That night, in a private suite in the Bellagio theater, complete with red privacy curtains and velvet-backed seats, I’d been fitted with an EEG built into special headgear–surface electrode caps, they’re called–that looks like a swimming cap that just happen to have about two dozen wires, each of which has a colored LED at the base, connecting me to a nearby computer. Barely able to move for fear of disturbing the wires, and having been instructed specifically not to clap during the performance (because although “it’s the worst thing to ask people at a show like this,” doing so might mess things up), I was about to be observed and measured for science.

The research at “O”–which was done side-by-side with a control study on a small theater show in New York that is known to generate joy and positivity, but not really awe–was a reflection of Cirque’s awareness that, although the entertainment company has worked hard over the last three decades to measure fan satisfaction, there was something it wasn’t capturing in the way fans reported their experience of watching a Cirque du Soleil show.

With no one else in the theater, save for a few acrobats rehearsing on the stage below, I talked with Lagacé and Kristina Heney, Cirque’s chief marketing and experience officer, about the genesis of the experiment.

“We were seeing an emotion on the faces of fans in theaters, arenas, and big tops around the world, and they weren’t able to convey it to us in a way that we felt we were getting the full scope of the picture,” Heney tells me. “We’d do the typical marketing word clouds, and we’d see ‘awesome’ and ‘oh my god,’ and then we’d see the ingredients of the theatricality–‘acrobatics,’ ‘music,’ [and] ‘costumes.'”

But the disconnect was the emotion, Heney says, and so when the team felt like it had reached the end of its means in terms of typical marketing work, it reached out to Lab of Misfits to see if science could help explain the emotions that Cirque performances elicit.

Cirque du Soleil is one of the best-known and best-loved entertainment brands in the world, but it nevertheless thought it had a broader branding problem. Although a Young & Rubicam study had shown that it was the most differentiated brand in North America–at least when it came to uniqueness and what the brand “brings to the table,” explains Heney–the Y&R study revealed that its relevancy factor was was low, particularly among millennials.

For Cirque, performances that make an impact are vital, particularly in connecting with the audience emotionally, not only immediately after the show, but into the future. You can’t just take in a Cirque show anywhere or anytime–they’re not on TV, or generally available online, and at any given time, they’re only in 15 or so cities around the world. So the company needs to develop lasting relationships with both existing and new fans that will inspire them to keep buying tickets, either in destination cities like Las Vegas or when the traveling shows come to town.

“We felt like we needed to better understand this emotional bridge,” Heney says, “in order to maintain that relevance, and really, truly hear what our fans wanted from us.”

As a student of emotions, Beau Lotto, a world-renowned neuroscientist and the “head misfit” at the Lab of Misfits, was himself thinking about the challenge of re-creating awe in order to study it. “And here we were, trying to describe an emotion that we didn’t have the language to describe, and neither did our audience,” says Heney of Lotto. “We immediately got along . . . and when I found out his company is called The Lab of Misfits, it was kindred spirits.”

It would be tempting to roll your eyes when you hear that a giant entertainment company like Cirque du Soleil–which is planning its own theme park, recently bought The Blue Man Group, and is always designing new shows–is conducting an experiment to study awe. But for Heney, it’s actually essential to understand something like the emotions its audiences feel as it plans for the future. “There’s a lot of potential around our greater organization to be able to explain how we connect to our fans,” Heney says. “For the last 34 years, we’ve focused on circus arts to create that emotional connection, and we’re evolving.”

Self-reporting

In the weeks prior to heading to Vegas for Cirque’s neuroscience experiment, I–and many Cirque ticket buyers–took an online Lab of Misfits questionnaire that aimed to figure out who might be a good fit for the study. The questionnaire presented statements, such as, “I have experiences that are indescribable,” or, “I have experiences that stir my soul,” and asked how true they felt.

Though Lab of Misfits didn’t reveal the exact purpose of its work with Cirque, the introduction to the questionnaire noted that it wanted to understand how immersive theatrical experiences affect the brain. Because I was working on an article about Cirque’s experiment, I knew I’d be taking part, and what it was.

But for everyone else who was chosen, its exact nature was a surprise until arriving in Las Vegas. In exchange for free tickets to “O” and an upgrade to one of the VIP suites, they agreed to be poked and prodded, and have their brain activity observed during a performance.

Back in Vegas, sitting with Lotto, I asked him why awe has traditionally gotten the short shrift when it comes to attempts to understand emotions. “Maybe it’s like consciousness itself,” Lotto tells me philosophically. “It’s difficult to study something that is difficult to define. And maybe as we are starting to understand these other emotions, we are starting to better define what awe might be and how to better define it. And in some sense, that’s what it is to be a bit of an adventurer–that you are stepping into territory that is, itself, not so easily definable.”

But while Lotto looks and talks like a philosopher, he’s actually a scientist, and there’s no doubt that his, and Cirque’s, goal with the experiment is to be able to point to emotions that people watching the “O” performances were feeling and say, without a doubt, which moments in the show generated awe.

“Maybe if they experienced awe, and we knew where, we could say, ‘This is you on awe,'” Lotto says. “‘This is your brain on awe, or your brain on Cirque.'”

The Cirque Way

In her previous life, Heney worked for the NBA, and she’s intimately familiar with the emotional swings on the hardwood. “In a basketball game,” she says, “it’s King [Lebron] James doing a buzzer beater in a playoff game. You get it. [But] here, it’s been a little more obscure for us.”

Heney and other executives in Montreal are well aware that there’s no way to predict what Lotto’s research will show, or even if the findings will be in any way meaningful. But Cirque du Soleil is an organization that champions audacity, looking at things upside down on the theory that doing so can make you better appreciate things that are right-side up. That approach is known as the Cirque Way.

And it’s the Cirque Way of taking risks and trying unknown things that led the company to set out on this journey to define and quantify awe. “It’s why we feel empowered to try a scientific test that we have no idea what’s going to come out of it,” Heney says. “We have a deep feeling of responsibility to figure something out, but it’s this idea that if you’re moving forward, and trying new things, you’re not failing.”

Takes you out of the moment?

As a self-professed Cirque nerd, the one thing I didn’t expect when I set out to take part in the neurological experiment is how I’d actually feel during the performance. I first saw “O” in 1998, and I saw it again a number of years later. In both cases, I was well and truly, yes, awed. How could you not be by some of the incredible acrobatics, divers jumping balletically dozens of feet into the water, Russian swings, and more?

Yet here in Vegas in April, an EEG strapped to my head, and told not to clap, wondering when the next prompt from the iPad would be, I found myself distracted and constrained, and left to over-analyze my own feelings of awe.

I wasn’t the only one. After the performance, I pulled aside Hailey Dean and Jeffrey Dimas, a couple who’d come to town for their anniversary and who had been recruited for the experiment. Although Dean says she is excited to find out how her own brain reacted during the show, she agreed that actually participating impacted her experience. “I think it was a little harder to have actual expressive feelings when you’re hooked up to something,” she told me. “I was a little bit worried that if I’m moving a little too much, is my brain stopping working right now?”

Something else she said was interesting, too, and it matched what I’d felt: The iPad questions that would pop up every few minutes, asking, among other things, about the level of awe we were feeling, would often come at very low-emotion moments in the show. It turns out, that was exactly by design. “We went through the show and selected times that are more likely to elicit awe than others, and also times that are less likely to exhibit awe,” says Lotto. “We are looking for a correlation between the magnitude of their expression and their response in their brain.”

Back in Japan, Noto writes to me that during an “O” performance, she experiences joy, excitement, thrills, nervousness, sadness, humor, hilarity. And afterwards, she says, “My heart is full of happiness and gratitude to this mind-blowing show.”

Cirque du Soleil knows it offers something different than other kinds of entertainment, and it wants to know exactly what’s different. The theory is that the shows generate awe in a unique way. Now, the question–which we won’t know the answer to for several months yet–is whether science can prove it.

“If there’s actually a powerful emotion that they’re taking out of the theater with them, that they can’t explain to me,” Heney says, “it’s my obligation to try to label it so that we can communicate it to our 4,000 employees, so artists can feel it, so our finance community can feel, and so that everyone within our organization can feel it.”

I asked Noto if she experiences awe when she watches “O.” “Definitely yes,” she responded in all capitals. “I am always overwhelmingly awed at the beginning of the show, the moment . . . the red curtain is blown away and the pool looks like a quiet lake, [and] then the music starts. It gives me goosebumps and chills every time.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.