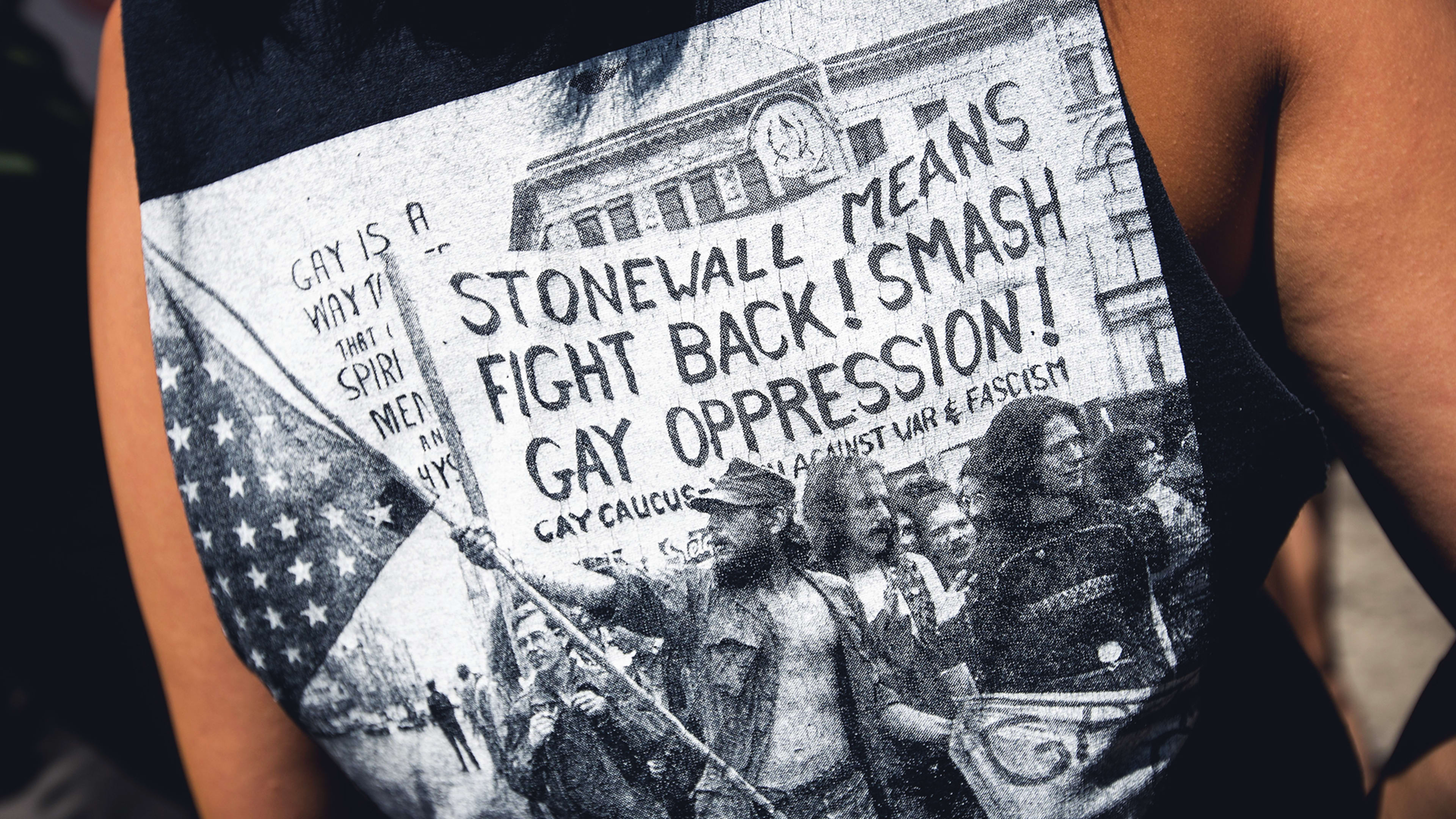

June was designated Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride Month, in part for remembrance of the Stonewall Uprising that occurred on June 28, 1969. LGBT patrons of New York City’s Stonewall Inn clashed violently with police after the bar was raided. The following year, marches were organized in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago to commemorate the riots and advance the Gay Liberation Movement in the U.S. Today, memorials, events, and pride parades happen all month long in an effort to recognize the impact that LGBT individuals have had on history locally, nationally, and internationally.

However, in the absence of sweeping federal legislation (and several recent legislative measures that aim to curtail rights), LGBT workers are still under threat on the job. In more than half of U.S. states, you can be fired for being gay or trans. So many LGBT workers choose to check that part of their identity at the door when they head to the office. Diversity and inclusion initiatives aside, it falls on the companies that rely on their LGBT employees and customers to advocate for their rights in the workplace.

Related: Four ways every company can advance LGBT rights in 2018

Here is a brief timeline of how LGBT workers’ rights and state and federal legislation have evolved and progressed (and in some cases, taken steps backwards) since the 1920s.

The origins of advocacy and the pink triangle

Back in 1924, German immigrant Henry Gerber founded what is known to be the first documented gay rights organization in Chicago. The Society for Human Rights was inspired by Gerber’s service in the U.S. Army during World War I by the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, a “homosexual emancipation” group in Germany.

The language used in the Illinois nonprofit’s mission was a reflection of the times. It aimed “to promote and protect the interests of people who by reasons of mental and physical abnormalities are abused and hindered in the legal pursuit of happiness which is guaranteed them by the Declaration of Independence,” including the right to work without the threat of firing. Not many joined, and even medical and psychological professionals were reluctant to advocate lest their professional reputation get ruined. After a series of arrests in the summer of 1925, the Society for Human Rights was dissolved.

Persecution continued through the next two decades. During World War II, the Nazis also held gay men in concentration camps and designated them with a pink triangle badge, which was also given to sexual predators.

Undeterred and inspired by Gerber’s original organization, Harry Hay launched the Mattachine Foundation in 1950. Founding member Dale Jennings started another organization called One, Inc., which welcomed women and would go on to win a lawsuit against the U.S. Post Office, which in 1954 declared the organization’s magazine “obscene” and refused to deliver it.

One law takes jobs, others decriminalize, still another is ignored

In 1953 President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an executive order that banned gay people—or, more specifically, people guilty of “sexual perversion”—from federal jobs. This lasted for about 20 years.

During this time, Illinois decriminalized homosexuality by becoming the first state to do away with its anti-sodomy laws. Others followed suit slowly over the next few decades, and in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the anti-sodomy law in Texas, effectively decriminalizing homosexual relations nationwide. However, there are still 12 states that have sodomy statutes.

In January 1975, the first federal gay rights bill that would prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation is introduced. The Judiciary Committee never brings it up for consideration.

Dishonorably discharged

Later that year, Air Force Technical Sergeant Leonard P. Matlovich, a decorated Vietnam vet, is ousted from the service when he comes out to his commanding officer. It would take five years for the Court of Appeals to rule that his dismissal was improper and award him back pay and a retroactive promotion.

Ten years later, President Bill Clinton makes a campaign promise to lift the ban against gays in the military.

Without ample support for this measure, he passes “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) in 1993, which kept gay men and women in military service as long as they kept their sexuality under wraps.

In 2011, President Barack Obama repealed DADT, but by that time, more than 12,000 officers who refused to stay silent had been discharged from military service. The U.S. Department of Defense announces that it will have a six-month delay before allowing transgender individuals to enlist in the military “to evaluate more carefully the impact of such accessions on readiness and lethality.”

This past March, the White House announced a policy to ban most transgender people from service.

Workers’ rights given and taken

Wisconsin becomes the first state to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation in 1982.

In 2013 the Supreme Court ruled to allow the government to deny federal benefits to married same-sex couples. However, in 2015 the Supreme Court ruled that states cannot ban same-sex marriage, making gay marriage legal throughout the country. The ruling doesn’t explicitly protect gay and lesbian employees who can still be fired for their sexuality in 29 states. Those who are transgender aren’t protected in 32 states.

Related: Here’s everywhere in the U.S. you can still get fired for being gay or trans

Kimberly Hively, an instructor at Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana, wins a case against her employer of 14 years for denying her full-time employment and promotions and eventually fired her because she is a lesbian.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions says the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 doesn’t protect transgender workers from employment discrimination. A judge appointed by President George W. Bush had previously ruled in that lawsuit that the Civil Rights Act does cover gender identity.

This past February, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit published an opinion that discrimination in the case of sexual orientation is a form of discrimination. Also this month, a U.S. appeals court in Manhattan ruled that a federal law banning sex bias in the workplace also prohibits discrimination against gay employees, becoming only the second court to do so. They followed Chicago’s Seventh U.S. Circuit, which was the first to rule that Title VII bans LGBT discrimination in the workplace.

This June, the Supreme Court issued a narrow ruling in favor of the baker who refused to serve a gay couple based on his religious beliefs in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, overturning a previous ruling on the grounds that the Commission was overly biased against the baker’s religion in this case. On the surface it appeared that the Supreme Court was condoning discrimination based on religious beliefs.

In a statement, the ACLU wrote that the ruling “reaffirmed the core principle that businesses open to the public must be open to all . . . The court did not accept arguments that would have turned back the clock on equality by making our basic civil rights protections unenforceable, but reversed this case based on concerns specific to the facts here.”

Until definitive federal legislation is passed, there is much work to be done to guarantee LGBT workers the same rights as their heterosexual counterparts.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.