As crowds pack into the Lyric Theater in New York City to ogle at a grown-up Harry Potter travel through time in the Broadway play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, there are several backstage characters who presumably wish that they, too, could go back into the past and rewrite history.

Those would be executives at Warner Bros. and its parent company TimeWarner. For while the studio owns most of the entertainment rights to Harry Potter and its spin-off series Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them–including films, live-action television, video games, theme park attractions–J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter’s creator, controls everything else. That includes the stage rights to her works, which means that, although Warner Bros. is a partner on Cursed Child, which is currently the hottest play on Broadway, the studio is not a lead producer or the primary stakeholder. In other words, Cursed Child is a Rowling production (along with producers Colin Callender and Sonia Freeman).

And then there’s AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson, who is trying to acquire TimeWarner for $85 billion, precisely because he intends to exploit the company’s “premium content” and distribute it to AT&T’s 100 million-plus mobile, internet, and cable customers. Harry Potter, whose value is estimated at $25 billion, is the greatest prize among TimeWarner’s content cache. (Yes, even more than Batman and the rest of the D.C. Comics universe it would also acquire.)

At a moment when all of Hollywood is desperate for giant pieces of IP (the industry term for “intellectual property”) real estate, the Harry Potter struggle reveals how fraught it is to try to beat Disney at its own game. Warner Bros. is now fighting to do just that with all of its big-name properties, but in the case of Potter it has to align its own ambitions with a business-savvy author intent on controlling her creation. As the decision nears on the AT&T-TimeWarner deal (the ruling will come no later than June 12) the Harry Potter journey is one that both consumers and any franchise-hungry media moguls can learn much from.

Unlike Harry and his cohorts in Cursed Child, no one can grab the sorting hat to travel back in time and recalibrate things that were set in motion years ago. AT&T and TimeWarner are trying to merge because it’s no longer enough to be a wireless provider or a movie studio that makes great films. But is it too late?

Harry Potter’s early days: “Let’s see how the movies turn out”

When Warner Bros. optioned Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone from Rowling in 1999 for $500,000, there was grumbling from some executives within the studio about the price of the option. Although the first book in the series was taking off in the U.K., it had yet to hit U.S. shores, so very few people had any idea who Harry Potter was. An oft-repeated question was: Why spend half a million dollars on a children’s book? The in-the-dark period didn’t last long. Within months, Harry Potter was on the cover of Time magazine.

More so than any other studio, Warner Bros. had a reputation for being artist-friendly. In the early aughts, directors and stars like Clint Eastwood and Kevin Costner had deals on the lot, helping bolster the studio’s reputation for making quality adult films. Rowling, who was flown out to L.A. and wined and dined at executives’ homes, was the latest creator to be warmly welcomed to Burbank.

While Rowling was no P.L. Travers, the British author of Mary Poppins, who famously caused Disney much angst while adapting that book into a film, she was particular about her work and had no desire to just take her Hollywood check and walk away. From the beginning, she was involved in nearly every step of movie-making, from choosing the directors of the films to going over scripts.

Rowling’s agency, The Blair Partnership, declined to comment for this story.

But Warner Bros.’ desire to keep things cozy with Rowling combined with its focus on making great films—as opposed to great multimedia brands—set up a scenario that limited the company commercially in many ways. When Rowling said she didn’t want to create any animated properties around Harry Potter, fearing it would cheapen the brand, Warner Bros. agreed to a mutual blocking right, meaning that Rowling would have to okay any such plans. (To date there have been no animated Harry Potter projects.) And she presciently carved out the stage rights to her books, setting herself up nearly two decades ago for the lucrative position she’s in now with Cursed Child, which in April grossed more in a single week than any other Broadway non-musical in history.

“I don’t know if anyone had the vision as grandiose as J.K.’s to know this would be a multi-billion-dollar franchise,” says one former Warner Bros. executive. “That wasn’t even a word back then.”

Although some credit goes to Rowling’s literary agent at the time, Christoper Little, for being the negotiating power in her corner, Rowling was undeniably protective of her literary baby. With the exception of a Coca-Cola tie-in on the first two Harry Potter movies, which the author only approved because the spots were built around a get-kids-to-read message, commercial deals were almost always nixed.

“We left a lot of money on the table not doing Happy Meals,” says the former Warner executive.

“It was so painful to get things approved,” says another former employee. “There were so many restrictions.” Unsurprisingly, when someone suggested doing Harry Potter-themed toilet paper, it was a “big no.”

Rowling’s wishes aside, Warner Bros. was also very clearly oriented towards making movies above all else. While it had a strong consumer products arm that it had used to leverage its Looney Tunes brand, sources say that at the time it didn’t think about Harry Potter as a product to be exploited every day of the year in every way possible. Although there were toy lines and other merchandising, the overall attitude was, “Let’s see how the movies do,” says a former executive.

“That’s very different than Disney, which fancies itself a magic experiences complex that does parks, resorts, and consumer products,” this person goes on. “There was no machine in place to say, okay, these guys will do your play, these guys will do your merchandise.”

“I think we did a good job back then,” says Josh Berger, Warner Bros.’ President of Harry Potter Global Franchise Development. “We were particularly focussed on making great films and Jo was particularly focussed on writing the books. Today the world is different but J.K. Rowling’s stories remain at the heart of what we do.”

Timing also played a part in why Harry Potter wasn’t able to be more of a franchise exploited by all the in-house divisions. In 2001, the year that Sorcerer’s Stone was released and Harry Potter costumes and Gryffindor scarves started flying off shelves, Warner Bros. shut down its 130 Warner Bros. Studio stores, which were struggling due to a downturn in the retail market. In 1998, just before it acquired the first option on Harry Potter, it sold Six Flags, the theme park company that owns Magic Mountain and other amusement parks around the country. Although it still worked with Six Flags to develop rides around its D.C. superheroes, Warner Bros. turned to another studio—Universal—to develop a theme park attraction around the Harry Potter franchise.

Warner Bros. eventually opened its own Harry Potter tour in London at the Leavesden studio, where the films were shot. But one former executive argues that even had Six Flags still been under Warner Bros.’ ownership for Harry Potter, the studio was not deeply invested in theme parks beyond licensing characters for rides. “It took Universal to make something special out of the Harry Potter experience that Warner Bros. never would have done with Six Flags. It was something they never thought of doing.”

Polly Johnsen, another Warner Bros. studio executive at the time, echoes this: “I think people are forgetting the reverence towards the books. They were instant classics as they were coming out. You have to be careful if you want to preserve that. I think if Warner Bros. had handled it any differently, people would have smelled a rat. There’s always a battle between creative and consumer products, which is always saying, ‘Yeah, we could have done more.'”

Warner builds a franchise while trying to keep Rowling happy

For any cavils about Warner Bros.’ missed opportunities, the company deeply invested in keeping its talent happy. The studio had a reputation for its “precious management of the creator,” as one former executive put it. In the early days, and especially after DiBonaventura left, president Alan Horn became the studio’s nurturer-in-chief. Known for his ego-less approach to talent and old-world manners, Horn developed a strong relationship with “Jo,” as Rowling is known on the lot, a priority.

“I think he just sensed early on, that to preserve the sanctity” of the films, Rowling needed to be brought into the fold, says Johnsen. “Of course, there’s a Machiavellian business thing, but I don’t think anyone was thinking that. Warner Bros. was always like an old-school studio. Talent, and especially directors, were respected. She became the Clint Eastwood of the studio.”

Horn declined to comment.

In 2004, the torch was passed to Diane Nelson, a marketing executive who had grown closer with Rowling over time; she became head of the global franchise management team that was established to keep Harry Potter on track. The creation of such a team, which combined executives from multiple departments across TimeWarner, was a first for the company, which is notorious for operating as a fiefdom of competitive silos. “Diane had to change an entire culture that was not used to collaborating,” says a former Warner executive, who only half-joked that meetings with people from other departments had to be done in secret. “I remember being at these Harry Potter meetings,” recalls Johnsen, “and there were like 40 people in the room. We’d never done that before.”

As the former Warner exec adds, “A studio like Disney is wired to do synergy and leverage corporate priorities. That’s not the case at Warner Bros. Diane and others had to machete through the jungle to get people to report to multi-department meetings. It was nearly impossible. There was no appreciation that one and one could be three.”

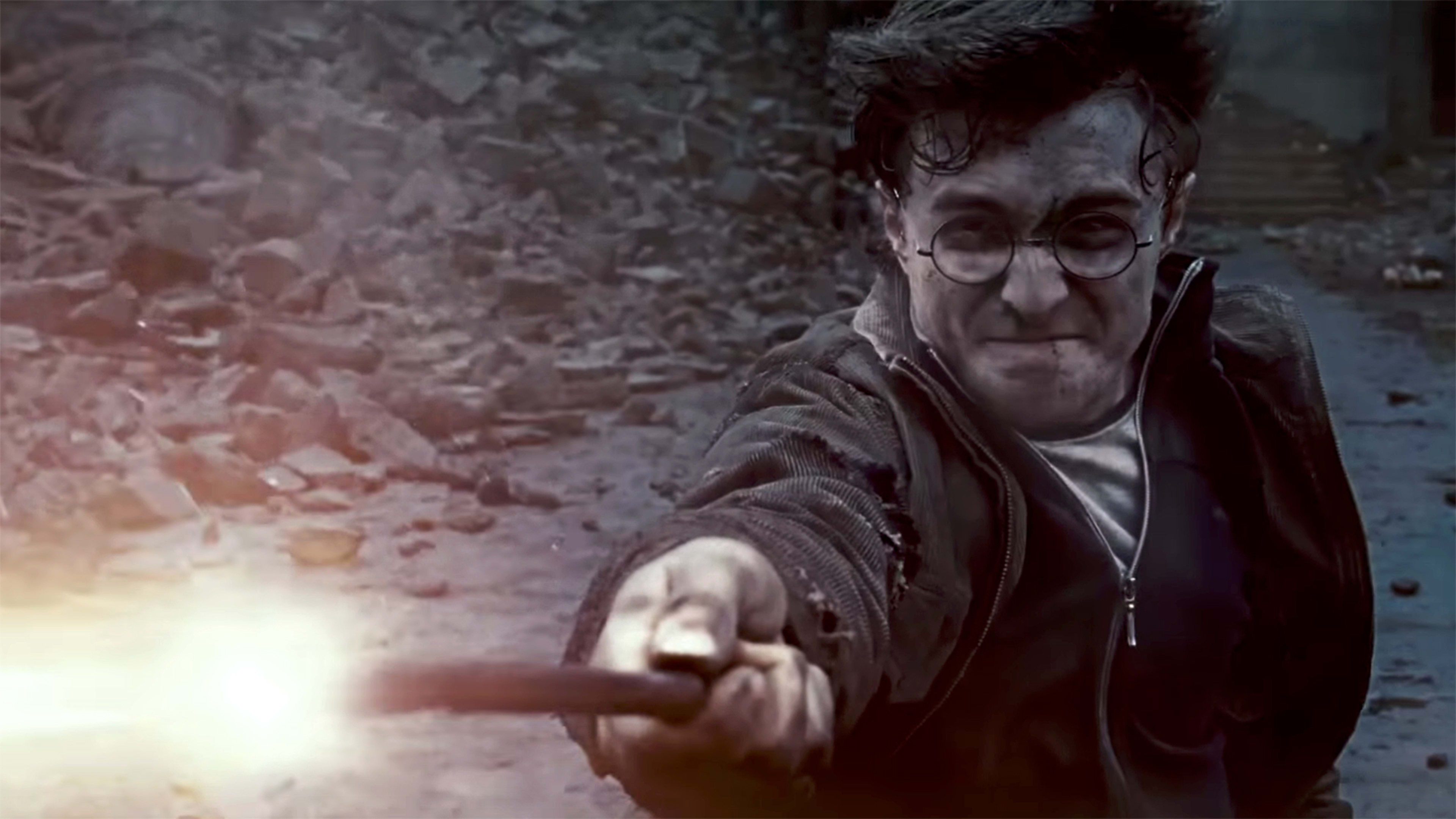

Meanwhile, the movies hummed along. The final installment, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (the studio cleverly stretched out the final book into two films) alone made $1.3 billion at a time when crossing the billion-dollar mark was a rarity. The eight movies based on the books, released between 2001 and 2011, racked up $7.7 billion in grosses. Moreover, they were praised by critics and cineasts for remaining true to the books while allowing artistic-minded directors like Alfonso Cuarón and Mike Newell to steer the films in a darker, more adult direction as the kids in the books aged up. Indeed, Harry Potter marked a modern golden age for Warner Bros., which found itself in the No. 1 slot amongst studios for years running during the Potter years. (New Line’s Lord of the Rings trilogy also helped the bottom line.) The films brought an almost invincible feeling to the lot, according to Johnsen. “We knew there was always another Harry Potter coming around the corner. It made things looser; we could have failures. I don’t think we felt the disruption as much as other studios did.”

Disruption, at least internally, eventually hit in 2011, when Horn stepped down in a company-wide shake-up, a few months after Deathly Hallows 2 came out. Now the job of negotiating with Rowling over the future of the studio’s gold-star franchise was in the hands of Barry Meyer, Horn’s partner who stayed on at the studio until the executive transition was complete.

This changing of the guard coincided with Rowling seeking more control of the empire she’d created. That same year she dropped her long-time literary agent and sought representation with Neil Blair, a lawyer and business partner of Rowling’s, who set up an independent literary and talent agency, The Blair Partnership. Observers have speculated that because Blair was not a traditional agent who received a 15% commission fee, Rowling was able to take greater control of her publishing interests. According to a former Warner executive, Rowling was also looking for more control of her movie assets. “She was chafing about restrictions,” this source says. “It wasn’t financial. Financially, she’s been significantly rewarded. It was never about the money. I think she just felt, ‘I created this, I want to determine where it goes.’ ”

Rowling’s requests didn’t get far with Meyer, who one source described as an “old-fashioned lawyer” and a “stickler for following contracts to the letter.” (Meyer did not respond to an email request to comment for this story.) With negotiations at an impasse, Rowling turned to another studio, Sony, to help her create a website, Pottermore, where–in another sign of her growing independence–she sold her e-books directly to fans. “She created this whole world with Sony, they gave her more creative control,” says the source, who adds that the move “embarrassed” Warner Bros. Rowling also teamed up with the BBC to create a TV series based on her first adult book, The Casual Vacancy. Rowling, who only produced the last two Harry Potter films, executive produced the series with Blair. “The statement was, ‘I’m gonna go where I want to go,'” says the source.

As Rowling flexes her power, TimeWarner gives away the store

The in-limbo state between Rowling and Warner Bros. ended in 2013, when Kevin Tsujihara became the new chairman and CEO of the studio. A former home entertainment and digital executive, Tsujihara “understood the lifetime value of something more than a TV or movie person,” notes one former executive. Which is why making things right with Rowling was a top priority for the new chieftain. “He personally took it upon himself” to woo Rowling, says another former Warner exec. “He gave her a lot of attention.”

Within months of his appointment, the partnership with Rowling was recharged, establishing a path forward for Harry Potter. A new spin-off series, Fantastic Beasts, was announced, with Rowling both producing and writing the series (a first), whose five films extend out to 2024. Warner Bros. also became the global distributor for A Casual Vacancy, and new theme park attractions were announced for the Universal parks.

“Kevin gave her a broader berth,” says the source. “He gave her that creative control. He chose to interpret things more liberally when Barry left. Jo ended up getting more of” the Fantastic Beasts franchise. “That’s how he won her.”

Today, “we are partners, working closely with Jo Rowling’s agent, Neil Blair,” says Berger, who took over as head of the Harry Potter global franchise team in 2014, when Nelson left to oversee D.C. Entertainment. “We figure out together how we’re going to develop the franchise, produce content and create new businesses and experience to delight the fans.”

Says another Warner Bros. source: “Under Kevin, this is a 24/7/365-day-a-year franchise.”

To this end, Warner Bros. released the mobile game Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery, in April, and in a day it shot to No. 1 as the most-downloaded game in both the Apple App Store and Google Play stores. Excitement is building for the Harry Potter: Wizards Unite augmented reality game from Niantic, the same developer behind Pokemon Go, that will debut later this year. It is also launching new Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts toy lines.

Behind the scenes, though, there are signs that there is not always such a shared strategic vision between Rowling and the studio. In 2016, Warner Bros. filed a request to acquire the merchandising and other rights (including motion pictures) to Cursed Child in the U.S. Around this time there were reports that Warner Bros. had met with actors from the Harry Potter films—Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grit—to discuss making a Cursed Child movie trilogy. Rowling swiftly shut the rumors down by tweeting, “This. Is. Not. True.” Warner Bros. also denies that it has any plans for a movie version of Cursed Child.

This. Is. Not. True. pic.twitter.com/BAzuKJiCOO

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) January 20, 2017

In March of 2017, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office denied Warner Bros.’ request, saying that it would cause confusion with Rowling’s own trademark for Cursed Child. In its response to the USPTO, Warner Bros. stated that it was “one of the world’s leading media companies” and that Harry Potter is “famous”—which it proved by saying that a Google search of Harry Potter yielded over 110 million hits. “Finally,” Warner Bros. wrote, “Applicant is the owner of over 50 trademark registrations at the USPTO for or containing the famous HARRY POTTER trademark.”

Brian Conroy, a trademark and brand protection lawyer in Dublin, Ireland, described the exchange between Warner Bros. and the USPTO as “curious.” Warner Bros.’ lawyers made no attempt to suggest that the application was with J.K. Rowling’s knowledge or consent,” Conroy says. “It would be very interesting to know if she knows or knew about the application.” He also pointed out that Cursed Child “is one of the only Harry Potter properties where Warner Bros. doesn’t appear to have a solid interest.”

A Warner Bros. source says that the trademark request is still in process and that the studio expects it will be approved.

Meanwhile, Warner Bros. is readying the second Fantastic Beasts film, which comes out in November, and trotted out the film’s star, Eddie Redmayne, at CinemaCon last month. So far, the franchise, which stars Redmayne as Newt Scamander, a “magizoologist” who arrives in 1920s New York to document an array of magical creatures, is performing well, if not at Harry Potter levels: The first film grossed $814 million worldwide. “I think Fantastic Beasts did fine,” says a former executive. “But I don’t think it knocked anyone’s socks off. The problem with these things is that (the Harry Potter films) were record-breaking movies when they came out. I don’t think they are replaceable.”

Well, perhaps not in Hollywood. On Broadway, Rowling is certainly making a case that they are. Whether any of that magic can be leveraged into a movie or other properties will soon be in the hands of AT&T, creating another new chapter in Rowling’s Hollywood journey.

All that can be said for certain is that, like the Harry Potter novels themselves, there will be no shortage of intrigue and surprising twists, something Rowling seems intent on ensuring. In late April, she cryptically tweeted: “I’m in a meeting with Warner Bros. and I can’t really concentrate because look”—attached was a tiny, Lego-like figure of a Niffler, one of the magical creatures from Fantastic Beasts. Fans immediately went to town speculating: Was the meeting about the next Fantastic Beasts movie? A Lego version of FB? A movie version of Cursed Child?

For now, at least, Rowling isn’t telling.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.