You’d expect a Starbucks at the company’s corporate headquarters in Seattle’s SODO neighborhood to be a bit of a showplace. But the coffee kingpin really upped the ante with the Starbucks Reserve SODO, which opened two and a half months ago on the ground floor of the former Sears Roebuck distribution center it calls home.

You can, of course, choose from an array of coffee drinks here, including some unique to this location; staffers roam the floor and take orders on tablets. But you can also belly up to the bar and order an aperitif. Or tuck into a surprisingly memorable slice of pizza made by Princi, a Milan-based café chain which operates a 10,000-foot bakery, visible through glass walls, on the Reserve’s premises. The sprawling Reserve space also features an abundance of wood and leather surfaces; an art installation made up of 3,700 colorful informational cards about coffee blends; and multiple seating environments, from a ring of comfy chairs surrounding a fireplace to secluded nooks where you can plunk down a laptop and work in privacy.

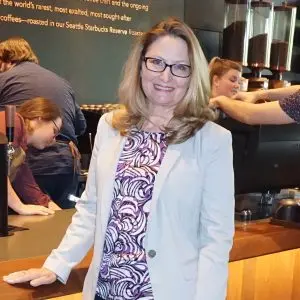

In many ways, this process needs to be invisible. “When you walk around the store, you see a lot of people talking to people, a lot of engagement between the baristas and the customers,” Starbucks CTO Gerri Martin-Flickinger tells me. “And for tech to be done well at Starbucks means tech needs to enhance that experience, not get in the way of that experience.” (We’re chatting in the Reserve SODO store’s “library,” situated behind a rotating wall/shelf stocked with 1,200 bags of coffee.)

Martin-Flickinger, a veteran of Adobe, Verisign, and McAfee, arrived at Starbucks in 2015 as the company got serious about ramping up its tech aspirations. She’s since beefed up her team with hires such as senior VP of engineering and architecture Tal Saraf (formerly of Cisco, Amazon, and Microsoft) and senior VP of retail and core technology services Jeff Wile (ex-Disney). And she also made a strategic decision for Starbucks to move away from building its own technical infrastructure in favor of the cloud.

The histories of the two Seattle institutions, both founded in the 1970s, have long intertwined. More than 25 years ago, when Bill Gates previewed Microsoft technology that melded words, images, charts, and sounds into one document, he did so by demoing how Starbucks—then a newly public company with an impressive 165 stores—could create its quarterly statement. Today, Starbucks is run by a former Microsoftie: Kevin Johnson, the company’s president since 2015 and CEO since April of last year, was once responsible for the Windows business and oft-mentioned as a possible future Microsoft CEO.

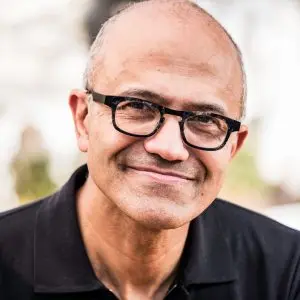

Starbucks’s desire to speak technology like a native is hardly unique. Actually, it’s typical among the sort of huge, well-established companies which are core to Microsoft’s business. “I’m working with Starbucks or a Boeing or a Maersk today like I may have worked with tech partners of the past, because they’re just like another technology company, and we are partnered with them,” Nadella says. “But it so happens that they’re using technology in consumer packaged goods or consumer brands or in logistics. And that transformation is just pretty stunning to see.”

For Microsoft, in other words, getting good at helping Starbucks figure out its future isn’t just good for Starbucks. It’s a critical part of Microsoft’s own transformation, with value that goes beyond its immediate contribution to the bottom line.

Scale And Its Challenges

At a mammoth retail business such as Starbucks, new technology most often calls attention to itself when it fails. In 2012, the company formed a sweeping partnership with Square, with elements ranging from Starbucks making a $25 million investment in Square to its stores accepting payment via Square’s Wallet smartphone app. The following year, however, in Fast Company field tests across the country, Starbucks employees often seemed baffled by the process of handling such transactions. Eventually, the two companies parted ways.

Since then, Starbucks has figured out mobile at least as well as any major retail brand. Today, U.S. customers use its app—rather than cash or plastic—to pay for 34% of orders. 12% of orders are placed in the app rather than at the counter; at 3,600 locations, that figure is 20% or above during peak business hours. “If you think about our worldwide footprint, that’s a pretty significant percentage of our stores,” says Saraf, whose responsibilities include customer-facing technologies such as Starbucks’s mobile and web presences. The popularity of mobile ordering has required recalibration of the workflow inside individual Starbucks locations, as the company worked to ensure that the feature reduced congestion in stores rather than increasing it.

Starbucks stores don’t have on-site IT experts to troubleshoot balky technology, and if something breaks, it’s likely to cause immediate problems. Those 100 million customer transactions a week are “small transactions, but there’s a lot of them and they come quick,” says Martin-Flickinger. “So you do not have room for ‘Oops, we’ve kind of slowed down’ or ‘Oops, we’re kind of backed up.’ Nobody’s going to come back and buy two cups of coffee tomorrow.”

The only way to know for sure whether technology will work in Starbucks stores is to try it out in the field, with real baristas and customers. Some of that happens at stores across the country where the company beta-tests everything from new beverages to kitchen equipment. But its technologists rely even more on a couple of dozen locations known as tech district stores, all located near headquarters in Seattle. “We want to be able to go at a whim,” Martin-Flickinger explains. “We want to sit in the store for half a day. We want to observe things. We want to get to know store managers. We want to get to know the partners behind the bar. We want to build a relationship with them, so that we become really an extension of that store experience.”

The tech district store I visit is a brief stroll from such Amazon landmarks as the Amazon Go store and Spheres—and seems to have a clientele consisting largely of Amazon employees, judging from the badges clipped to their clothing. It’s one of 1,500 high-volume locations that use a year-old software platform called the Starbucks Production Controller, which handles much of the logistics of in-person and mobile-order wrangling so that baristas have more time to devote to coffee and customer interactions.

The Production Controller helps support a system called the Digital Order Manager (DOM) which streamlines processes such as tracking an order for coffee and a pastry and making sure the customer knows when both items are ready. These tools are good examples of the sort of technologies that tech district stores help refine. And they’re powered by a bevy of Microsoft offerings, including various Azure services and the Surface tablet that the DOM runs on.

The Internet Of Starbucks Things

At the Starbucks Reserve SODO, the coffee is made using Clover X, a cutting-edge piece of beverage-making machinery which grinds beans and brews coffee a cup at a time, on demand and in under 30 seconds. Long in development and still in testing at a limited number of locations, with no public plans for full deployment, it already has Starbucks groupies giddy.

Along with its potential to usher in an era of consistently fresh coffee, Clover X presages a time when all the equipment in a Starbucks might be smart and internet-connected. Each unit is a node on the company’s Azure-based cloud, collecting useful data as it works and facilitating remote maintenance. “There’s no doubt in my mind that over the next three to five years we’re going to have dozens of internet-of-things devices in our stores,” says Martin-Flickinger. “And so we’ve been on this journey now for probably the last year and a half in earnest.”

Operating a Starbucks store currently involves countless mundane responsibilities that distract from the people-and-coffee heart of the business, many of which the company thinks it can automate. “Right now, there’s literally a requirement for our [employees] to go and record the temperature from the cold cases that have food in them and the refrigerators in the back of the house,” says Wile. “Why not put a sensor in there that records all that for them and frees them up for that time? We’re testing that right now.”

Then there are the warming ovens in each Starbucks, which are programmed to heat items such as an almond croissant for a specific time determined by the food-quality team. “At any Starbucks you go to, it should be the same experience when you bite into that croissant,” says Martin-Flickinger. But as the menu evolves, those ovens’ knowledge banks need to be refreshed—which the company currently accomplishes by shipping updates on USB drives to every store. “That’s craziness,” she says. “Wouldn’t it be much better if we pushed a button from here and the recipes went out?”

Sphere reflects a Microsoft mantra called the Intelligent Edge: the idea that commercial devices should not simply be connected to the internet, but pack a fair amount of their own computational muscle, allowing them to keep chugging even if they lose connectivity. The more the notion catches on with companies such as Starbucks, the better positioned Azure is to compete with the dauntingly successful Amazon Web Services, which defined the modern cloud platform and continues to dominate the category.

Already, Satya Nadella contends, Azure offerings relating to the Intelligent Edge have given Microsoft a competitive, well, edge. “This is no longer about even the story of, ‘Hey, Amazon built the first cloud hyper-scale business,'” he tells me. “We built the first hyper-scale cloud business with the edge, and we’re in the lead. And I love that.”

For all the ways in which Microsoft’s technological roadmap lines up neatly with Starbucks’, the human element of the partnership remains essential. “One of the things that has pivoted us in many cases towards Microsoft as a key partner in the cloud is that not only did they bring great technology solutions to us, but they brought great people for us,” says Wile. “That partnership with Microsoft people that we could parachute into our development teams helped this organization that was going through this transformation accelerate so much faster.”

Nadella, who is always quick to connect the dots between culture and technology, also emphasizes the human element of Microsoft’s relationship with companies such as Starbucks. “We have in some sense unlocked people’s pride in this company to create products that serve customers well,” he says. “It starts with listening, learning, creating a hypothesis, experimenting, being comfortable knowing when you got things wrong. And that’s what I think you see at play.” Maybe software, like Starbucks coffee, is at its best when it achieves scale without losing sight of personal connections.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.