On a weekday afternoon last spring after school, a group of teenagers in the Bronx performed an experiment: They walked around a single block and documented all the signs saying that they weren’t welcome. On apartment building walls, signs said “no loitering” and “no sitting” and “no playing.” At a restaurant selling buffalo wings, a sign said that there was a 15-minute limit for eating. In one corner store, a foreboding red sign said that anyone entering with a hoodie would be considered to be trespassing. A beauty supply store had a “no minors” sign, saying that the store would check IDs.

For the six teenagers, all between the ages of 15 and 18, it was the first step in a research and design project that looked at how many places youth were seemingly banned from hanging out, and the problem of a lack of public space for youth in the city. Working with designer, artist, and educator Chat Travieso, who had recognized the problem in some of his past projects with young people, they spent four months talking to public space designers, people working in the criminal justice system, city officials, and other experts, along with other teenagers. Then they began to rethink how public spaces can change.

Many of the black and Latinx young people they interviewed talked about being stopped by police or security just for being in a public space. One boy, who was 10 or 11, told the team about being followed by security at Target, who eventually told him that he needed to leave if he wasn’t going to buy anything.

“The kid was like, why are you doing this to me? There’s so many people here, why are you coming up to me?” says Monserrat Ambrosio, one of the teenage designer-researchers on the project, called Yes Loitering. “I think it impacted me because he was only 10 and he had already realized that because of his age and because of him being a kid of color, it really impacted the vibe of the space and how people treated him.” For slightly older students of color, the sense of constant surveillance can be even stronger.

In any location, teenagers often struggle to find a place to spend time with friends. But the challenge is greater in cities like New York, where families tend to live in small apartments without the room or privacy to invite people over. Most don’t have front or backyards. In the Bronx and elsewhere, apartment buildings often have “no loitering” signs even in their own courtyards. In some buildings, through a program called “Operation Clean Halls,” NYPD officers patrol hallways and move people who are “loitering”–an attempt, in theory, to cut down on drug deals, but a practice that can end up affecting anyone with no other place to go.

The Yes Loitering researchers heard repeatedly that people had especially negative assumptions about teenagers: They were seen as loud, reckless, disrespectful, dangerous. Store managers were quick to ask them to leave or to call police. New York City says it’s starting to shift away from its aggressive broken windows-style policing strategy, which sends people to court for minor crimes like sitting in a park after the park has officially closed, but young people still get criminal summonses for a minor crime.

“This idea of being in the wrong place at the wrong time–just because a police officer at a certain time might want to stop you or ask you questions or because you were in a store and being too loud and they kicked you out, or you get in a fight in school, all these things could end up with you having a criminal record,” says Travieso.

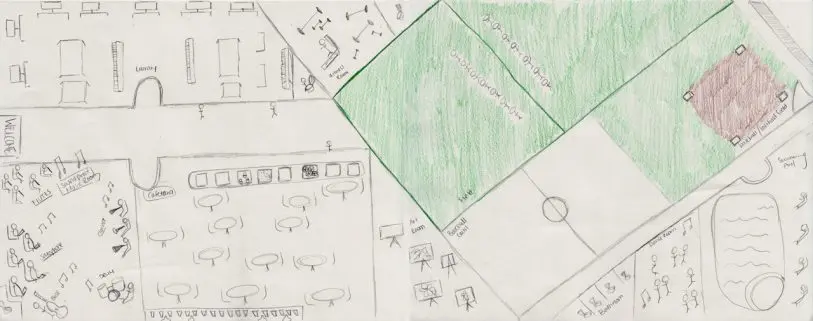

After researching the problem, the students started to think about solutions. Though a handful of spaces explicitly designed for teenagers exist, they think that’s not enough. “When people think of creating spaces for young people they think of a youth center or they think of a skate park,” says Travieso. “Those are great and we should have more of those, but we should think of the city itself–the streets, the sidewalks, everywhere that’s a public space, and also spaces where people congregate like restaurants, as being spaces that are also welcoming to teens.”

Parks should have Wi-Fi, seating, and shelter from rain, they suggested. Bathrooms should be gender-neutral and accessible without buying food or drink. Affordable food should be available. There should be more places to play different types of sports. More spaces should be open late or 24 hours. All of these things could benefit other New Yorkers as well.

“The fact that people consider young people or other people who are experiencing homelessness as undesirable leads to very unpleasant public spaces for everyone . . . it eliminates so many amenities that everybody would actually appreciate and embrace,” Travieso says. “I think we need to kind of reframe the way we think of the commons and the spaces that we all kind of share because young people and people who are experiencing homelessness are also people, human beings, who deserve spaces, and who deserve dignity.”

As recent events at a Philadelphia Starbucks–where two black men were arrested just for waiting for their friend–show, the culture of anti-loitering policies aimed at minorities extends far beyond the Bronx, and far beyond just posted signs. “What happened at the Starbucks in Philadelphia is an all-too-common example of how black people are systematically criminalized in our cities,” says Travieso. “It lays bare the double standard for how businesses enforce store policies depending on a person’s race.”

Ambrosio says in the past, she had taken “no loitering” signs–and other ways to exclude people, such as spikes on ledges to prevent people from sitting down–somewhat for granted. “We kind of normalize it,” she says. After working on the project, that has changed. “Not too long ago I was going to go into a store and I noticed that I wasn’t allowed to go in without a guardian,” she says. “I had my sister with me, but I was like, I don’t want to support that business. They don’t want me. It’s something that I’ve talked to my friends about. I feel like I’m more aware of it.”

The team hopes that its suite of suggestions can help policymakers and designers improve cities. It also thinks that teenagers should be actively involved in redesigning public space–not simply offering opinions, but helping develop solutions and having a say in what is implemented. “Young people are leading so many movements right now,” says Travieso. “I think adults need to stand back and listen.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.