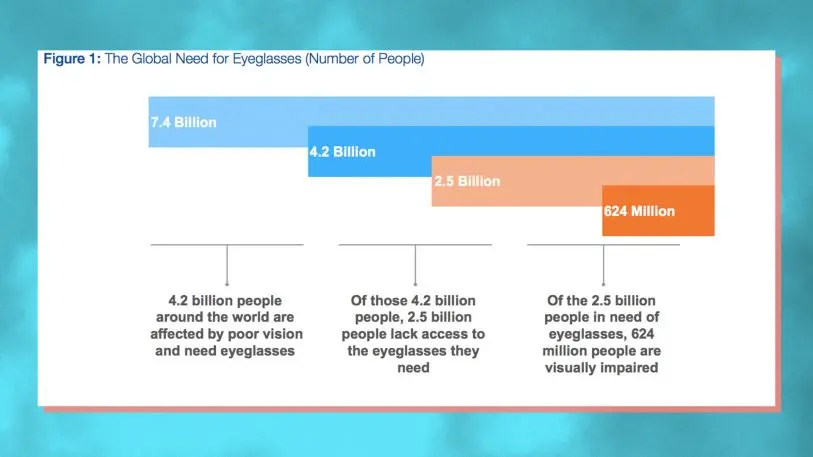

If you’re reading this with the aid of glasses, count yourself lucky. Up to 2.5 billion people in the world need eyewear to see clearly but don’t have access to it, according to a new report.

This lack of eyewear is a highly fixable problem with enormous economic and social benefits, including better learning in schools and fewer road accidents. Philanthropists looking for big bang-for-buck impacts on their investments could do worse than eye-tests and prescription lenses. The results are proven and impressively large.

The report, from the Overseas Development Institute, a London think-tank, brings together data on the economic impact of eye-care and suggests some funding models to get the sector moving. It says governments often lack the resources to intervene, but that foundations and philanthropists can catalyze markets, with big potential results.

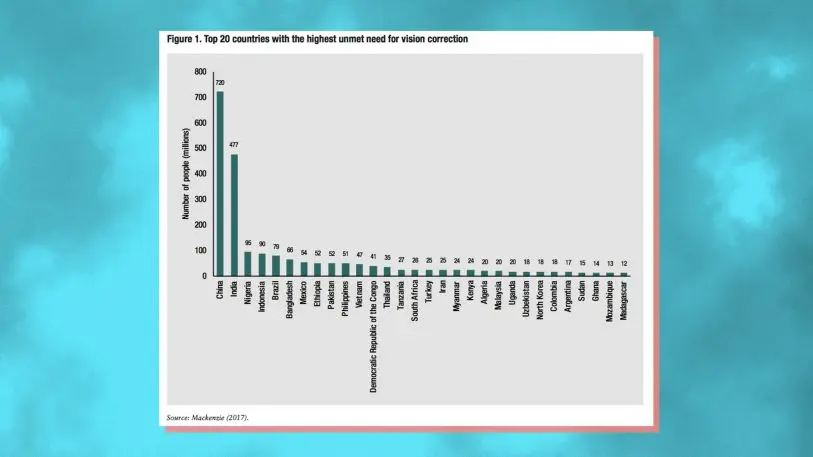

For example, it estimates that offering glasses to all agricultural workers who need them would net $180 billion in total economic benefits (in higher farm yields, for instance). That includes an added $19 billion in India, $10 billion in Nigeria, and $2.5 billion in Malaysia.

School children are particularly affected by poor vision, because an estimated 80% of all learning occurs visually. Correcting a child’s vision has the equivalent benefit of half a year’s additional teaching, the report says. Indeed, a review of 60 health interventions aimed at primary schools found that vision-correction has a greater economic impact than deworming kids or improving their nutrition. Up to 239 million children still live with uncorrected poor vision.

“Providing citizens with clear vision would accelerate progress, helping deliver poverty elimination, quality education, and gender equality, and avoid leaving those without access to primary eye-care behind,” says Elizabeth Stuart, head of ODI’s growth, poverty, and inequality program.

Other economic studies show similarly large results. One by consultants PwC found that spending $57 billion on eye-care in developing countries by 2020 could produce a total productivity benefit of $228 billion. Groups like VisionSpring and Vision for a Nation report economic returns of 30 to 1.

VisionSpring, a social enterprise based in New York, has distributed 3.9 million pairs of glasses since it was founded in 2001. It sources glasses in bulk, manufacturing in Asia, then sells them on at a small markup (typically that means $1 per pair for manufacturing and a $4 final price, according to the report). It also trains “vision entrepreneurs”–commissioned sales reps who visit villages and sell glasses to end users. Warby Parker has a one-for-one program (you buy a pair, they give a pair) and has worked to reduce the cost of eye tests. Other approaches rely on mobile phones to do eye testing more cheaply.

The report looks at potential financing models for philanthropists to get involved. These include blended finance (where private capital stands beside public investment), results-based financing, development impacts bonds (where funders can profit if pre-agreed goals are met), social enterprises, and challenge funds, where entrepreneurs are encouraged to submit business plans in return for startup capital.

“Without scaled-up investments, the cycle of poor eyesight and low education, health and productivity outcomes in developing countries may continue,” the report says. “Investments in addressing poor eyesight will positively impact people’s lives and enable them to realize their potential.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.