Editor’s note: Stephane Kasriel is CEO of Upwork and currently serves as the co-chair of the World Economic Forum’s council on education, gender, and work. This essay reflects the views of this author, but not necessarily the editorial position of Fast Company.

Artificial intelligence is the rare kind of issue that can turn an event as broad and all-encompassing as Davos on its head. This year, AI grabbed hold of the Swiss outpost and supercharged the conversation with a palpable shift in tone. In just one day, more than 20 news dispatches about AI came out of Davos in Bloomberg alone.

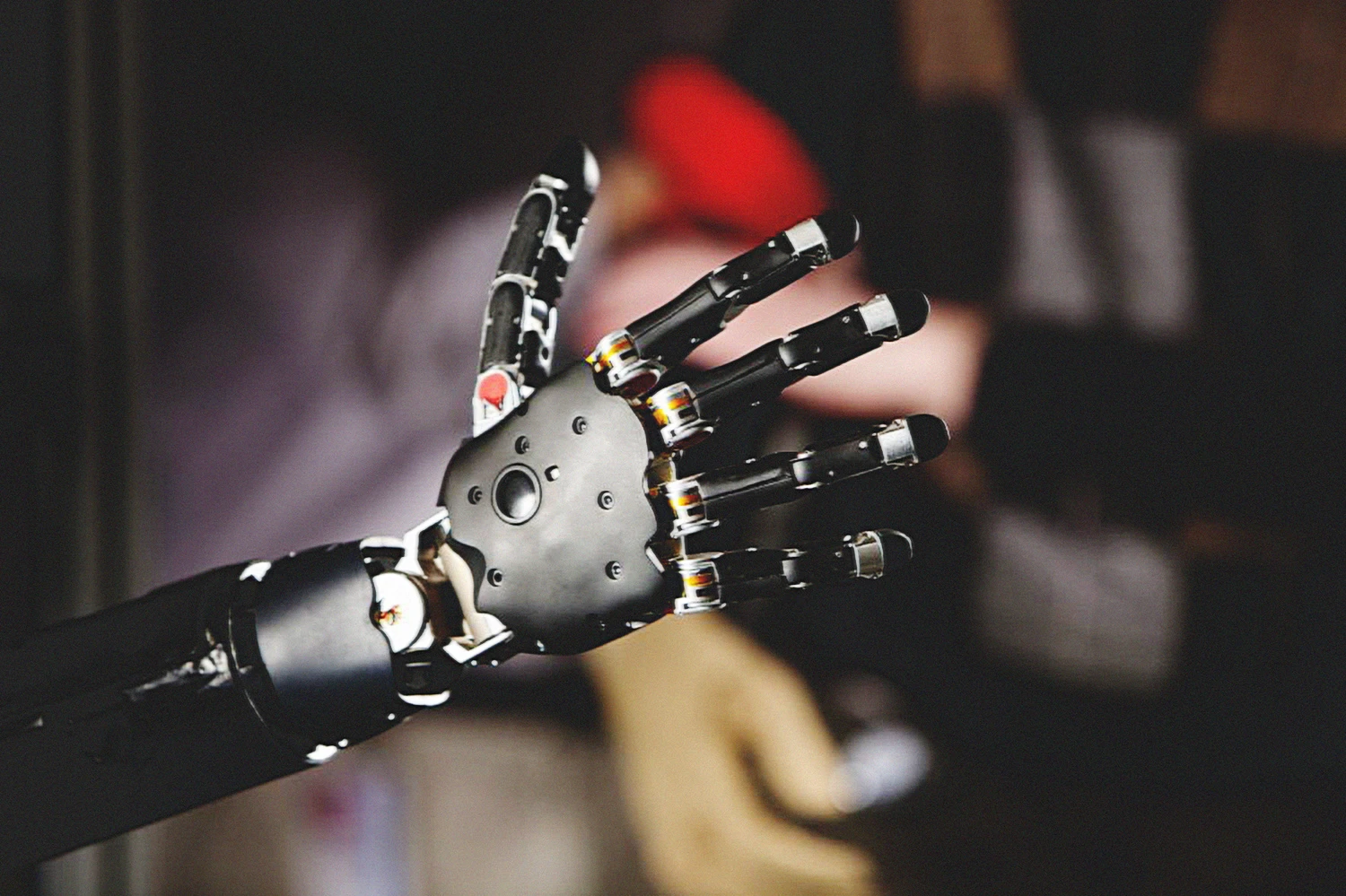

It’s not hard to understand our AI obsession: For years, many of Silicon Valley’s highest-profile leaders, from Elon Musk and Marc Benioff to Bill Gates, have issued warnings about coming waves of automation, saying that they could threaten our jobs and ways of life.

This year’s World Economic Forum gathering in Davos included some of that alarmism. Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, reiterated his own prediction that AI and robots aren’t only going to take a lot of jobs, they’re also going to start World War III.

But Ma’s comments felt out of date this year.

Instead of imagining a future of robot overlords, the vast majority of Davos attendees with whom I spoke or heard commentary from instead said they now envision AI augmenting our strengths, not replacing them. Think Iron Man, not Terminator.

However, outside of Davos, Ma’s–or, for that matter, Musk’s or Steve Wozniak’s–alarmism is still all too common when it comes to predicting the future of work. And that’s not a good thing. Fearmongering threatens to create the dismal future we all seek to avoid. Envisioning negative outcomes can help us better prepare for the future, but can also pave the path to them. Simply put, we can’t let our anxieties become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Related: How Demographics, Automation, And Inequality Will Shape The Next Decade

To get a sense of the extent to which fear of AI has crept into our psyches, consider the results of Pew Research Center’s survey last fall.

When it comes to advancing automation of jobs, Americans are almost twice as anxious as they are excited. Among U.S. adults, 72% say they’re worried “about a future in which robots and computers are capable of doing many jobs that are currently done by humans,” according to Pew.

Gallup’s latest polls on AI, released in January, show that many Americans “remain largely positive about the impact the new technology will have on their lives and work over the next decade.” At the same time, three in four Americans believe that AI will destroy more jobs than it creates.

These are depressing statistics because they’re self-reinforcing. If more and more people expect robots will take over their jobs, what incentive do they have to invest in new skills? Won’t their next job be automated, too? Without answers to those questions, how does a worker even go about deciding what new skill to learn?

But if, instead, we envision positive potential outcomes, we can plan accordingly by discussing how to best point ourselves in their direction. Fortunately, new research gives us a practical guide to think seriously about future-of-work solutions and, by helping foster constructive conversation, also provides some relief from the anxiety all this fearmongering creates.

Lost, Found

In collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group, a January WEF report, “Towards a Reskilling Revolution,” set out to create a “building block for workers looking to find their place in the future of work and for business leaders and governments looking to build more prosperous companies and productive economies and societies.” Using the United States labor market, it looks at the jobs most likely to disappear next as a result of technological change, and then examines the practical job options for the displaced.

No one knows how fast artificial intelligence will advance, and without knowing that, it’s impossible to say how many jobs will truly be lost. An OECD study from 2016 estimated that 9% of jobs are threatened by automation while another study says 50%.

The WEF/Boston Consulting Group report shows that the number of jobs lost might not actually matter very much. Why? Because it finds that the skills used to perform the jobs most currently at risk of being automated will help these workers transition to new careers less at risk of automation.

As I’ve argued before, work is not a fixed pie that machines are eating a bigger and bigger piece of while humans get less and less. New technologies create new jobs, too. Cars killed off the horse and buggy, but replaced it with a giant auto industry. In the 1980s and ’90s, as banks began installing ATMs everywhere, people assumed bank tellers would lose their jobs, but that’s not what happened. Banks used the savings they reaped from labor-saving tech to open more banks and change the job of a teller to be more of a customer service rep, and today banks employ more tellers than they did in 1980.

Of course, we can’t expect displaced coal miners to all become software engineers. So what skills will translate to new jobs?

Turns out, a lot.

The U.S. government’s Department of Labor predicts that 1.4 million workers currently employed will be displaced by technological disruption by 2026. But when the WEF studied Labor Department data, its analysis found “good-fit” job transitions for 96% of those 1.4 million workers.

Office clerks might be replaced. But the WEF report says their skills could translate well to being a customer service rep. And software might displace legal secretaries, but the report says their skills make them a good fit to be paralegals.

From Fear To Action

While few countries have taken action in this area, there are some national examples showing what’s possible.

Singapore has launched a lifelong learning initiative that’s focused on developing future-oriented skills that can help enhance workers’ productivity. The WEF has also praised the apprenticeship and vocational training programs of Germany and Switzerland. Germany’s Educational Vocation Act, for example, provides 500,000 Germans with two to three years of classroom instruction combined with paid on-the-job apprenticeships.

Unfortunately, the United States hasn’t yet taken the lead. There are no national plans to tackle the issue. And while a lot of discussion is developing around the idea of a universal basic income, that is a distraction, not a solution. Education and training are what matter, and solutions addressing them are most urgent.

Related: These Two Silicon Valley Pizza Places Show The Challenges Posed By Automation And Inequality

Just last week, for instance, AT&T announced a billion-dollar retraining initiative. The company has one of the largest workforces in the world and, when research showed only half its employees had the STEM skills they needed, it decided to take action. According to Bill Blase, senior vice president of human resources at AT&T, the company chose to “try to reskill our existing workforce so they could be competent in the technology and the skills required to run the business going forward.”

While AT&T’s move is promising, I still know of no public-private partnerships like Germany’s or Switzerland’s to train the 1.4 million workers that U.S. government’s own analysis predicts will be displaced within eight years. As it stands, the U.S. spends less on vocational training as a percentage of its GDP than almost every other country in the developed world.

But that can change. We must enter the next wave of automation prepared, because we can either build the future we want, or be changed by it. First, though, we have to change our conversations themselves, from less anxious predictions to more discussion of how to work toward positive outcomes.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.