Satellite broadband service has always been that thing your uncle in Idaho uses to connect to the web. He complains about the big dish he had to lug up to the roof and aim at just the right point in the sky. He complains about the cost. He complains about the high latency of the service–the old “click and wait” while the signal travels from the dish out to space and back again. But out where he lives, it’s the best he can get.

In other words, satellite internet has been the service of last resort for people who live in places where cable and telco broadband can’t reach. But that may begin to change as a next wave of satellite technology begins entering orbit over the earth over the next few years.

Home broadband service seems ripe for disruption. Cable and telephone-company broadband service is, for the most part, not a great value on a price-per megabit basis. That’s partly because it’s usually sold in markets with little or no real competition. Why has satellite never provided a disruptive alternative to the cable and telco offerings? The answer is pretty simple–it’s never tried.

“We have always been clear that our mission is to serve the unserved and underserved populations,” said Hughes Network Systems’ VP of marketing Peter Gulla. “…we don’t target our marketing toward areas served by high-speed cable internet.” HughesNet is currently the largest satellite internet service provider in the U.S. The company, which began offering satellite broadband in the 1990s under the DirecPC name, was acquired in 2011 by EchoStar, which operates the satellites used by pay-TV provider Dish.

Gulla says Hughes estimates the total unserved and underserved market to be around 18 million U.S. households. Other estimates have put it at between 13 million and 15 million. Either way, it’s big. HughesNet has about 1.5 million subscribers today.

The entire addressable fixed broadband market in the U.S. is, of course, far bigger–well over than 100 million subscribers, 40% of which get their connectivity from Comcast.

Satellite’s Challenges

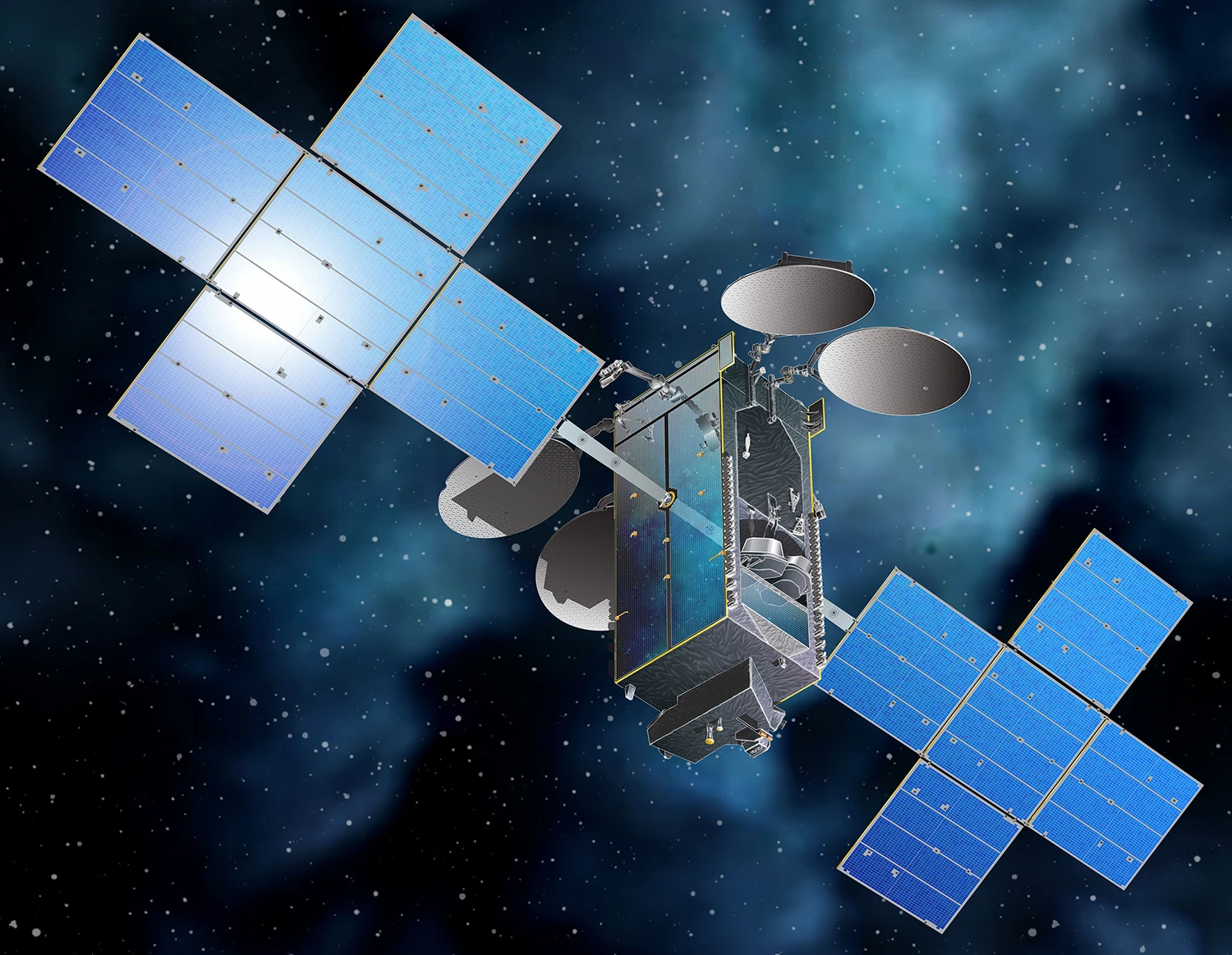

There are good reasons why HughesNet can’t be competitive in the nation’s more populous areas. First of all, it’s very hard, and very expensive, to blast big chunks of equipment up into space on the back of a rocket. One study showed it costs $4,653 per kilogram, and large satellites can weigh up to 10,000 kilograms, or 11 tons. (The current generation of satellites themselves cost between $10 million and $100 million.) So the number of broadband-serving satellites now orbiting the earth is limited. HughesNet has just two of them.

The broadband capacity of the satellites is also limited, says PwC’s global tech, media, and telecom principal Dan Hays. That is, each one can support only so many customers in a given part of the world. In fact, as of late last year, HughesNet’s first generation Jupiter satellites were said to be supporting all the subscribers they could handle. HughesNet says its next generation satellite, called Jupiter-3, will offer far more capacity and deliver speeds of more than 100 megabits per second (Mbps). The Jupiter-3 satellites are expected to begin launching in 2021.

There are serious technical challenges, Hays explains. In order for a satellite to receive a web request from a user on the ground there must be a clear line of sight between the user’s dish on earth and the receiver on the satellite. So cloudy conditions can slow network performance, a problem called “rain fade.”

There are power considerations. “There’s a certain frequency of signal that needs to be used to penetrate the earth’s atmosphere,” Hays points out. “And remember that these satellites are powered by solar energy, so they also have to balance the signal input power with the power of the satellite.”

The LEOs Are Coming

The “last alternative” role of satellite service may not last forever, though. Changes are afoot in the industry.”What you’re seeing now is the satellite companies saying we’re going to put up these massive constellations of low-altitude satellites to provide broadband for the whole planet,” says Hays.

These new satellites, called Low Earth Orbit or LEOs, will be smaller and lighter and could soon cost less than $1 million each. Some investors believe the cost of these satellites will drop to around $100,000, Hays says.

The new philosophy involves building satellites on an assembly line using inexpensive, mass-produced parts. Hays compares the approach to the way big tech companies deal with servers in huge data centers: they use off-the-shelf servers, and when a server blade malfunctions, they don’t spend time fixing it, they just replace it.

The approach extends to constellation management, too. If one LEO in a large constellation breaks down, the operator might just position another one to take its place.

OneWeb says it believes the new wave of lower-cost satellites could improve the economics of satellite broadband to the point where its service could be competitive on both speed and price with cable and telco services in the U.S. The company states that its first-generation satellites will deliver peak download speeds of 500 Mbps to subscribers. That compares to 25 Mbps with HughesNet; according to one study, the average download speed in the U.S. across all broadband services was 64 Mbps.

OneWeb’s main intended customer base remains the same unserved and underserved markets HughesNet targets, although HughesNet has said the two will be addressing slightly different market segments. HughesNet is an investor in OneWeb, and is already supplying satellite technology to the upstart. HughesNet says it will also be providing the ground systems that will deliver Internet access over OneWeb’s soon-to-be-launched constellation.

The Federal Communications Commission last June gave OneWeb permission to serve broadband to U.S. customers.

OneWeb will be competing with SpaceX, which has big plans to offer its own broadband service, delivered from a massive constellation of 12,000 low-orbit satellites. The company last month sent two of its own demo satellites into space on one of its Falcon 9 rockets. The Wall Street Journal‘s Rolfe Winkler and Andy Pasztor report (paywall) that SpaceX expects to sign up more than 40 million subscribers to its broadband service by 2025. That’s far more than the total current unserved and underserved households, indicating that SpaceX expects its technology to compete with more mainstream broadband options.

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai said last month that he wants the FCC to quickly give SpaceX its blessing to serve broadband to U.S. homes. SpaceX filed an application for the approval 15 months ago.

Ultimately, PwC’s Hays is skeptical about the price and performance of the services the new class of satellite providers will eventually sell. “It’s unlikely that it would compete on performance and cost with either cable or fiber-based service,” he says. But he adds that there’s still a lot we don’t know about the technology, value, and performance of the new services.

In the near term, this new wave of satellite service may at least let people in sparsely populated areas get fast, reliable broadband. That could make a big difference to small business owners in far-flung places. Better broadband might even influence some people’s decision to move far away from congested cities.

Further out, new low-orbit satellites could let companies like OneWeb and SpaceX offer solid broadband connections in metro areas, too. If these players offer a cost-per-bit proposition that puts big cable and telco ISPs on notice, it would bring the fixed broadband market something it so often lacks: real competition.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.