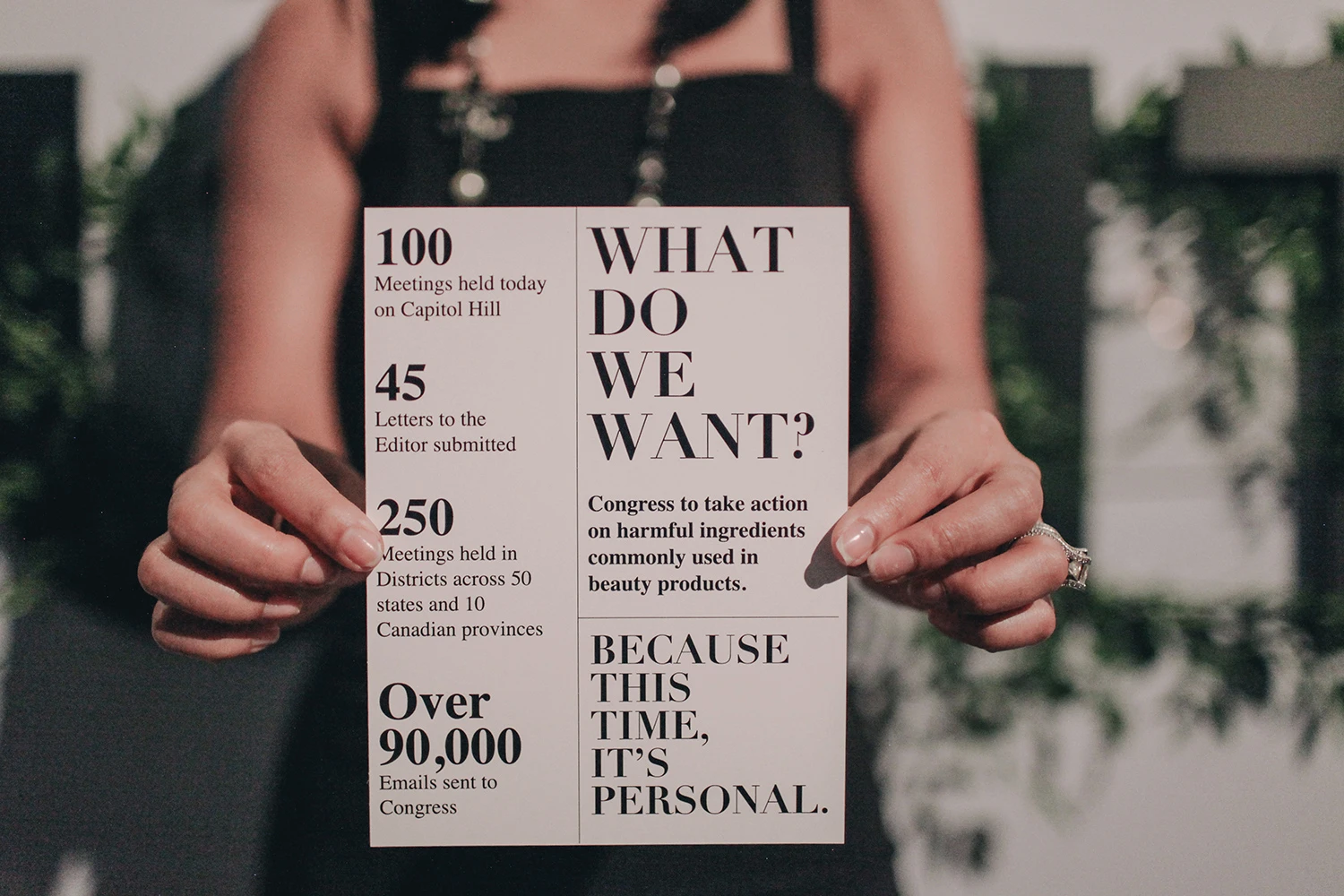

It’s 10 a.m. in Washington, D.C., and 100 saleswomen from skincare and cosmetics brand Beautycounter have gathered on the steps of Capitol Hill.

They’re in their finest pantsuits and shift dresses, makeup flawless, game faces on. They’re girding for a long day of lobbying members of Congress for laws to keep harmful chemicals out of the soaps, shampoos, lotions, and makeup Americans slather on their bodies every single day.

A few hours later, in the offices of Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-IL), 10 of them are sitting around a conference table to speak with the lawmaker’s legislative assistant. Among them is Jude Rollins, a Beautycounter salesperson (or consultant, in the parlance of the brand), who is in her 50s and lives in the Chicago suburbs. Although soft-spoken and out of her element, she nonetheless believes in the mission. It’s personal.

A decade ago, Rollins was diagnosed with breast cancer. It came as a shock because there was no family history of it and she had no known risk factors. “I exercised, I ate healthily, I don’t have any relatives with cancer,” she says. “The day my doctor called me, I remember he said, ‘I can’t believe I am telling you this right now’.”

The days after her diagnosis were a blur as Rollins set about learning about the carcinogens in her environment, trying to understand what might have triggered the tumor. That’s when she discovered how many harmful ingredients could be found in the seemingly innocuous bottles in her shower and makeup drawer. Formaldehyde, for instance, which is commonly used as a preservative in cosmetics, has been linked to cancer. Coal tar, which is used as a colorant and an anti-dandruff agent, is a known carcinogen. The list went on and on.

The European Union has banned more than 1,300 chemicals and restricted the levels in 250 others in soaps, shampoos, lotions, and makeup. Canada has banned around 600. In the United States, only 30 ingredients have been partially banned to date, and the last federal law to regulate the safety of personal care products was passed in 1938. Rollins is convinced prolonged exposure to chemicals in her beauty products may have triggered her cancer.

“I’ve long been interested in issues of environmental health and chemical safety—banning phthalates in baby products, ensuring labeling of packaging that contains BPA,” Feinstein says. “Addressing personal care products safety is critical to addressing broader concerns about how exposure to chemicals affect public health. We need to continue to build support and maintain a steady drumbeat.”

Rollins wouldn’t have come to Capitol Hill alone. She has no activist experience and wouldn’t have been able to navigate the labyrinthine halls of the Senate by herself. But over the last three years, that changed with the help of her employer, which has an entire advocacy wing led by Lindsay Dahl, the brand’s head of social and environmental responsibility. Dahl, the former deputy director of the U.S.’s largest environmental health coalition, Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families, played a pivotal role in pushing for the 2009 FDA ban of toxic BPA from plastic pacifiers, baby bottles, and sippy cups.

While other direct sales brands, like Avon and Mary Kay, dangle cars or cruises in front of salespeople to incentivize them to sell as much as possible, Beautycounter gives two top salespeople in each state an all-expense paid trip to Washington, D.C., to lobby lawmakers. Dahl’s team helps organize these meetings, and she’s there to answer any questions consultants might have about the process.

Beautycounter’s founder and CEO, Gregg Refrew, launched the company because of her passion for the issue. The brand effectively self-regulates with a team of scientists to formulate beauty and hygiene items free of 1,500 ingredients that are either harmful or questionable. Renfrew’s goal was to do more than sell products: She wanted to spark a movement to educate consumers and demand better regulation of the industry.

Rebranding Activism

While Beautycounter sometimes sells products through retailers like Target and Goop, the primary way they’re marketed is through independent salespeople like Rollins, who sell makeup and skin care products in their communities. It was a strategic decision for Refrew. “The problem we are tackling with safety in personal care products is complicated,” she tells me. “We really felt that the best way to communicate it to consumers and explain our mission was through personal relationships.”

Beautycounter has 30,000 consultants within its network. Given that they are from every corner of the country, these women tend to have diverse political persuasions and personal backgrounds. But 80% of them are drawn to Beautycounter for its social mission, according to an internal survey the company conducted. This activist approach sets it apart from the hundreds of other direct selling brands on the market, like Stella & Dot, Rodan & Fields, and Cabi.

Many Beautycounter consultants have become hardcore grassroots activists. At dinner, I sit next to Elaine Chiu from San Francisco and Christina Glickman from Chicago. Both were corporate executives for many years but, compelled by Beautycounter’s activist approach, left their careers. Between sharing parenting advice and talking about their favorite fashion designers, they display impressive political knowledge.

They are well-versed in the details of the PCPSA and understand the circuitous road to getting legislation passed by Congress. “We really would like for the bill to better define the word ‘safety,'” Glickman says. “As the bill currently stands, any company can create a product and describe it as safe, but for the law to carry any weight, we need a more scientific measure.”

Beautycounter has more than just made advocacy less intimidating: It’s made it downright glamorous. When the consultants arrived in their hotel rooms, Beautycounter had provided them with custom-made bags from the trendy designer bag company Parker Thatch and notebooks from the luxury stationary brand Appointed.

Beautycounter had released a new color, Beautycounter Red, to coincide with this day of lobbying, and the women showed up on Capitol Hill with vibrant coral lips. And after the day of meetings, the women gathered in gorgeous cocktail dresses at the Beautycounter party at the Newseum, where they drank champagne, dined at tables decorated with enormous white flower arrangements, and danced the night away.

None of this bears much resemblance to the kind of activism we’re used to seeing in the media. “Before I started the company, the idea of activism conjured up images of serious people filled with anger,” Refrew says. “But I really believe there are many ways to advocate for our rights. I want this movement to be filled with positivity and female empowerment.”

Brand Activism In Trump’s Washington

Beautycounter isn’t the only brand creating a way for people to engage politically. Seventh Generation, the green cleaning products company acquired by Unilever in 2016, has held rallies in support of a law that will force manufacturers to disclose what is in their industrial and consumer cleaning products. Ben & Jerry’s is famously political, taking stands on issues directly related to the ice cream industry—like opposing cow growth hormone (rGBH) and encouraging GMO labeling and free trade—and supporting progression groups like Black Lives Matter and those demanding climate justice and LGBT equality.

Patagonia just launched a digital platform called Action Works that allows people to learn about activism opportunities–from events to petitions and volunteering–that are taking place in their community. Patagonia focuses on protecting the environment and identifies issues that involve land use, water, climate, and biodiversity.

Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank New America, and author of The Business of American Lobbying, says the advocacy these brands are doing is not unusual. “This is just what companies do,” he says. “It’s what they have been doing since governments began regulating business. Companies are very powerful in politics, and to the extent that companies like these are advocating for progressive laws that will benefit Americans, I think this is a good thing.”

While Beautycounter, Patagonia, and these other brands have been actively engaged in political activism for years, the Trump administration’s rollback of regulations has raised new challenges. In Patagonia’s case, for instance, President Donald Trump has denied climate change, pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Climate Agreement, and cut funding for the Environmental Protection Agency. When Trump reduced the size of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments in Utah, eliminating nearly 2 million acres of formerly protected territory, Patagonia replaced its website with a black screen and the words, “The President Stole Your Land.”

Activist brands are serving a key role in the current political climate, when so many people feel despair about the state of the country. Brands like Beautycounter and Patagonia give their customers opportunities to act and make their voices heard.

It can also be tricky for companies to advocate for political change. They are profit-making entities that need to sell products and compete in the marketplace to be successful. And this sometimes raises thorny questions about intent. For instance, personal care product brands that already self-regulate their products stand to benefit if new regulations for higher standards are put in place, because they will be a step ahead of their competitors. Government regulations can help incumbent firms by creating barriers to entry for potential competitors, an idea articulated by Nobel Prize-winning economist George Stigler.

Dahl says not so, noting that should new regulation come to pass, companies in the market would have a long lead time to reformulate their products. And in any case, many larger multinational beauty brands already have formulas that they use in Europe, where standards are much higher.

“It’s not like our brand would have an overnight advantage,” Dahl says. “We know our brand–given our price point and product selection–will only appeal to a segment of the market. We’re pushing for legislation that would ensure that any product someone purchased would be safe.”

More broadly, Drutman believes it is a good thing to give people tools to get involved in the political process. Americans are not a very politically engaged bunch. Drutman believes that brands like Beautycounter are playing a valuable role by making politics and citizen advocacy less intimidating. “There are many ways to get engaged in the political process,” Drutman says. “Just because you got involved because of a makeup or clothing company doesn’t make your involvement any less valid.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.