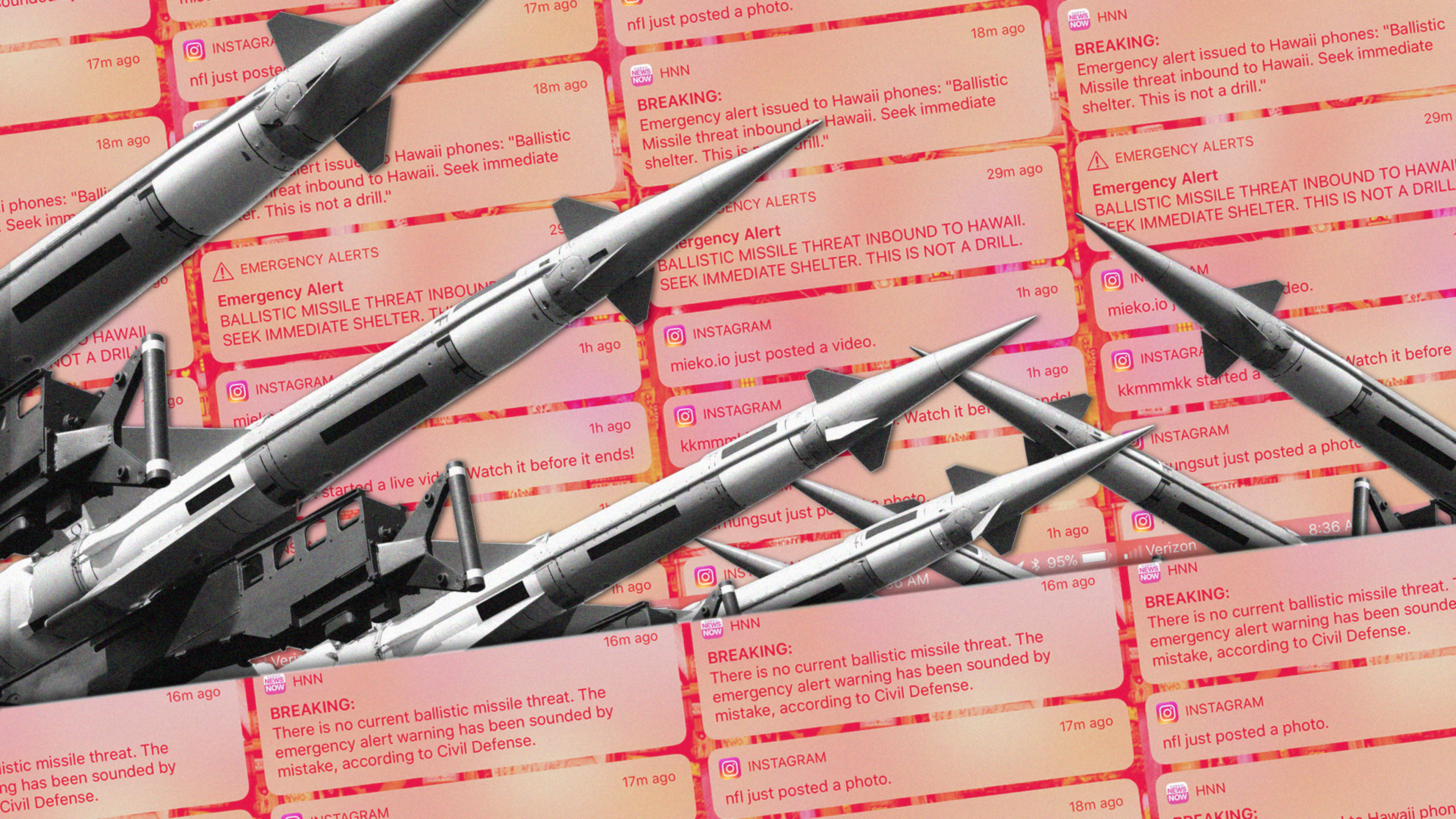

On January 13, 2018 at 8:07 a.m., Hawaiians were told the end was near. “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL,” proclaimed an alert sent through Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency, which notifies residents of Hawaii through the internet, smartphones, radio, and television.

By 8:10, the head of the Hawaiian Emergency Management Agency had confirmed with U.S. Pacific Command that the alert was false–but that didn’t stop it from remaining in place for an agonizing 38 minutes. In the interim before a follow-up correction alert was issued, Hawaii’s representatives took to social media to inform citizens. Senators Tulsi Gabbard and Brian Schatz tweeted that it was a false alarm, while Hawaii’s governor, David Ige, spent 15 minutes struggling to remember his Twitter password before tweeting his own reassurance. At 8:45, Ige announced that someone had “pushed the wrong button” during an employee shift change, while the White House gave a contradictory explanation that the alert was an “emergency management exercise.”

As tensions between the U.S. and North Korea rise, with each side increasing their nuclear arsenal and threatening to annihilate the other, there is no room for errors in communication. “The risk of accidental nuclear war is not hypothetical—accidents have happened in the past, and humans will err again,” tweeted former Secretary of Defense William Perry on the day of the alert. “When the lives of millions are at risk, we must do more than just hope that mistakes won’t happen.”

Senator Schatz agreed, tweeting, “The whole state was terrified. There needs to be tough and quick accountability and a fixed process.” Reiterating that the false alarm was due to human error, Hawaiian officials vowed reforms, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) announced it would investigate. Three weeks later, that investigation has already hit a snag: The unidentified employee who sent the alert initially refused to comply with the probe for unspecified reasons.

The employee then told officials that he sent the alert intentionally, believing it was real after hearing only the phrase “this is not a drill” extracted from a longer message. The FCC says that it is “not in a position to fully evaluate the credibility of [the employee’s] assertion that they believed there was an actual missile threat and intentionally sent the live alert.”

Everything about the false alert in Hawaii was unusual–the conflicting explanations, state officials’ reliance on social media, the unexplained time lag, and most of all, the fact that it happened at all. There had not been a false nuclear war alert since February 1971, when the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) sent out a televised warning of impending thermonuclear war, which was retracted 40 minutes later. While miscommunications about nukes occurred in the decades after–most notably in 1983, when a Soviet officer correctly interpreted an incoming warning as false, thus perhaps preventing nuclear war–they were very rare, and ceased after the end of the Cold War. January 13, 2018, was only the second time a false alert about an impending nuclear missile had been sent to the public.

January 16, 2018 marked the third time. In Japan, users who had downloaded an app from public broadcaster NHK received an alert that North Korea had launched a ballistic missile and that they should seek shelter. Unlike the Hawaiian alert, the Japanese false alert was corrected within minutes.

But two cases of false nuclear alerts in one week–after 47 years of none at all–raises disturbing questions. The false alerts arrived when the world is closer to nuclear war than at any point in human history, including, according to experts, during the Cold War. On January 25, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved their doomsday clock to two minutes to midnight, the most perilous position ever, due in part due to Trump’s enthusiasm for nuclear weapons and perceived openness to launch a preemptive strike as well as Kim Jong-Un’s nuclear ambitions.

Trump is the only person authorized to use nuclear weapons; the codes are his alone. While advisers from the Department of Defense would likely weigh in on his decision, their job is to carry out the order. As nuclear strategy expert Tom Nichols writes, the order makes its way through the chain of command very quickly, and “there is no countermanding this except by the same process that started it–that is, by the president.”

The process assumes a baseline level of competency in the president, which has been brought into question by Trump’s Twitter taunts and casual threats of deployment. During his State of the Union address on Tuesday, Trump declared that the U.S. is in imminent danger of a nuclear strike from North Korea, and that his administration was “waging a campaign of maximum pressure” to prevent it. That campaign apparently includes firing those who question Trump’s “bloody nose” strike strategy, like Victor Cha, who was removed on Tuesday from being the next South Korea ambassador for saying Trump’s reckless proposals endanger Americans.

In addition to the ongoing question of Trump’s temperament, we face a new crisis: Today, digital technology makes it easier than ever to manipulate officials and the public through false alarms. Throughout 2017, international officials warned that Russia had the capacity and intent to hack the telecommunications infrastructure of NATO states. This warning extended to the vulnerability of national and state alert systems, which hackers had attacked numerous times as the number of attempted and successful infrastructure hacks rose dramatically during the second term of the Obama administration.

While no official has claimed that either the Hawaii or Japan false alert was due to a hack, one can imagine why a hostile actor would hack an alert system if causing chaos–or starting a war–was their goal. Trump’s documented enthusiasm for using nuclear weapons (“If we have them, why not use them?” he famously said) is matched by his disdain for expertise. Despite having skilled advisers at his beck and call, Trump largely takes his policy cues from Fox News–in particular the show, Fox and Friends–to the point that intelligence experts worry spies will manipulate him through the network.

Trump also relies heavily on social media, where he has shown himself to be malleable, repeatedly posting conspiracy theories, retweeting a fake Fox and Friends account he believed was real. Trump’s Twitter account is, in many ways, a national security risk. Over the past week, two accounts that had the ability to send Trump direct messages–those of former Fox News anchors Greta van Susteren and Eric Bolling, whom he follows–were both hacked by a group claiming to be a Turkish cyber army, leaving the Twitter-loving president vulnerable to false information. (No investigation of the hacking has taken place.)

Trump says that the main source he consults on foreign policy is his “very good brain” and that this brain is so powerful it took him only an hour and a half to learn everything he needed to know about nuclear weapons. If a false alert goes out, and Trump hears about it through Fox News, a Fox News imposter account, or another dishonest social media account, will he launch a retaliatory nuclear strike without further verifying the information with NORAD or consulting advisers? False nuclear strike alerts are terrifying for the population in their own right–the Hawaii alert caused one man to have a heart attack–but the greatest danger may be the combined effect of the president’s gullibility, impetuousness, and enthusiasm for war.

As if this wasn’t troubling enough, last week the Pentagon raised new cause for alarm. After being criticized for not responding to last year’s spate of cyberattacks, it announced that their response to a massive cyberattack on infrastructure could be employing nuclear weapons–a radical new stance that former Assistant Defense Secretary Andrew C. Weber said would “make nuclear war a lot more likely.”

The Hawaii and Japan false alarms should be considered a wake-up call as to the need for clear official communication, impenetrable alert systems, and sensitivity toward how respective leaders and populations will react should an alarm occur. Japanese citizens, who have to live with actual missile tests from North Korea, did not share the understandably panicked reaction of Hawaiians, for whom the experience was new.

The frightened reaction of Americans was rooted not only in the terrifying unfamiliarity of receiving a missile alert, but in knowing that the administration has proposed using nuclear weapons on North Korea should they strike U.S. soil. Nuclear strikes are no longer a tactic of last resort, but perhaps a presidential preference. This marks a dangerous break from the past. With the missile alert system vulnerable to both human error and hacks, it is increasingly likely that fake news could launch a real war.

Sarah Kendzior is a journalist and scholar of authoritarian states.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.