Like many buildings in California, Uber’s San Francisco headquarters features a defunct rooftop helipad. Many were mandated by the state as a way to evacuate people during emergencies in the seismically challenged region. But even if building owners wanted to offer private helicopter service, economics and public outcry would probably stop them.

While science fiction gave us hovercars floating serenely across the sky, reality gave us obnoxiously loud helicopters beating the air into submission–something few commuters can afford and nobody wants to hear. But a convergence of maturing technologies has Uber and dozens of other companies betting fortunes on the decades-old dream of quiet, inexpensive, even eco-friendly air taxi service.

What makes such low fares even remotely plausible? With batteries charged on cheap electricity, clusters of small propellers that are quieter than the thunder of big helicopter rotors, and the ability to transform from vertical lift to airplane configuration, these imagined aircraft-of-the-future promise to substantially cut noise, cost, and the risk of accidents (like the fatal March helicopter crash in New York City).

The projected time frame for delivering these largely speculative craft, and for building physical and technological networks to support them? A mere five years. They would start out as human-piloted vehicles–but per Uber’s sales pitch, would evolve into fully autonomous ride-sharing flyers.

Related: Uber’s New Air Taxi Boss Built Flying Cars For Larry Page

Audacious by nature, these flying car claims are especially heady for a company that lost an estimated $4.5 billion last year on its earthbound taxi service.

Whether it soars or plummets, Uber Elevate–as the initiative is called–will be one of the boldest (and oddest) technological and business ventures in memory. The program must reconcile the ingrained caution of the aeronautical industry and government regulators with the fail-fast exuberance of Silicon Valley. It also requires Uber to radically change its modus operandi. The company must evolve from bullying its way into communities to courting invitations, from evading government authorities to winning their trust, from thinking it can do anything to recognizing its limitations.

After a year of speaking with people inside and outside Uber–allies and rivals, boosters and detractors–I believe that the Elevate team wants to make those changes inside Uber. But it’s too early to say if they can.

The Man Who Put Cars In The Sky

The germ for Elevate came not from an Uber executive, but from NASA’s chief technologist for on-demand mobility, Mark Moore. He and I first met in early 2008 at the second annual Electric Aircraft Symposium, a gathering of aeronautics die-hards (including Google co-founder Larry Page) at a hotel near the San Francisco airport.

At the time, Moore was finishing his PhD coursework in advanced aeronautic vehicles. He described to me a vision for electric planes quite close to what Uber and rival companies like Airbus are now developing.

Moore kicked off electric plane mania in 2009 with an adorable concept for a one-person commuter craft called the Puffin. Other projects followed, including the 2015 flight of a scale model for another design concept: a 10-propeller, tilting-wing plane called Greased Lightning.

“As I did these different technology demonstrators, I knew this technology was ready to be commercialized,” Moore says.

In August 2015, he called Jeff Holden, Uber’s chief product officer, to pitch the electric air taxi concept. He soon had a meeting with Holden, Uber CEO Travis Kalanick, and two other VPs. Moore brought along NASA colleague Ken Goodrich, an expert in flight control systems.

Their three-hour presentation focused on conceptual planes that perform vertical take offs and landings, known as VTOL. VTOL allows flying vehicles to maneuver in and out of small locations, like rooftops, and switch from rotors to wings to save energy.

“Helicopters aren’t very efficient because they’re always thrusting,” says Mike Hirschberg, an aeronautical engineer. “If you can transition to wing, then you can fly on much, much less power.” Hirschberg is executive director of an organization that, since 1943, was called the American Helicopter Society. In April, its name changed to the more-encompassing Vertical Flight Society.

Planes can achieve VTOL in several ways, like using a set of rotors for lift and descent, and separate propellers for forward flight (as the Larry Page-backed Cora plane does). Or they might feature tilting propeller motors or wings (like Greased Lightning’s) that rotate 90 degrees to point up, like a helicopter, and forward, like a plane.

Related: Uber Flying Car Chief Says Planes Won’t Deafen People Or Blot Out The Sun

VTOL is not a new idea, but new technologies are converging to make it practical.

“I remember DoT studies in the ’60s about the great future of [VTOL] air taxis,” says Hubert Horan, an airline industry veteran, transportation consultant, and stanch Uber critic. “Now we can have service every 15 minutes from Philadelphia to New York. You know, pie in the sky stuff.”

VTOL mechanics are too complex with big gas engines, says Moore. Only the U.S. military can afford such craft, like the V-22 Osprey. In the past, says Moore, “The amount of claptrap that was required just to get the vehicles into the air was so crazy that the maintenance, the payload [capability], were just horrible.”

“The simplification of the technology, combined with the sophistication that can be pushed into the software, has completely changed the landscape of what you can do with these flying vehicles,” says Allison. “It’s that basic insight, applied to larger scale airplanes… that Mark had pretty early on.”

Instead of one or two big, noisy, gas-powered engines, eight or 10 smaller electric motors can be distributed around the plane, to fine-tune airflow over the vehicle. Running on cheap electricity at over 90 percent efficiency, these motors cut fuel and maintenance costs and improve safety through redundancy.

“Helicopters have a few pieces that are critical, so you have to really, really work on them to make them safe,” says Rodin Lyasoff, head of Airbus’s rival to Uber Elevate, called Vahana. Electric planes can stay aloft even if they lose an inexpensive propeller or two.

With smartphones and electric cars pushing lithium-ion battery capacities, technologies finally converged to make electric VTOL doable, Moore told Uber.

“It definitely struck me as one of the types of paradigm shifts that I look for,” says Uber’s Holden. “How do we not get caught in a vortex of just everyday business?”

(Given Uber’s operating deficit, that is quite a vortex.)

Over the next year, Holden researched the technologies and projected consumer demand. He concluded that air taxis could be a viable business for Uber. In October 2016, the company issued a white paper laying out its ideas.

In February 2017, Moore ended his 32-year run at NASA and joined Uber as engineering director of aviation. At its April 2017 Uber Elevate Summit in Dallas, the company announced several key alliances with aircraft makers to build planes, with real estate companies to develop mini airports (called vertiports), and with two regions: Dubai and Dallas-Fort Worth. In November 2017, Uber added Los Angeles to its list of future launch cities. (According to sources and confirmed by Uber, Dubai’s participation is no longer certain.)

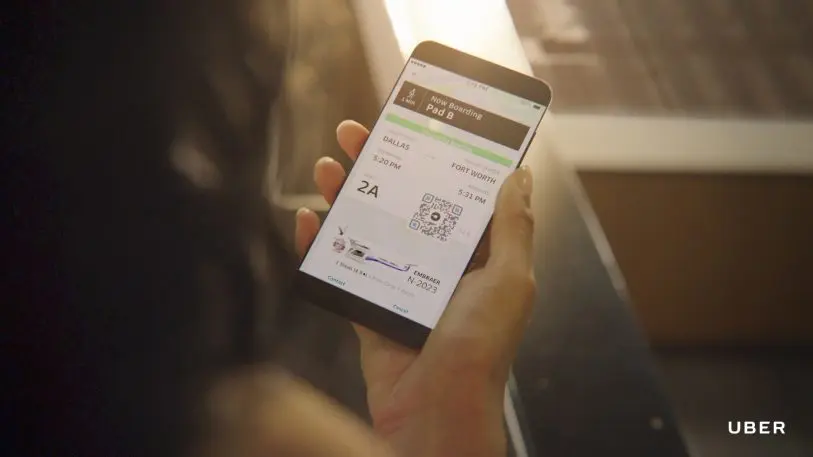

More partners may be announced at the second Elevate Summit, which Uber will live stream from Los Angeles beginning on May 8. Uber’s plan is to start demonstration runs of air taxis in 2020 and launch a commercial service, uberAIR, in 2023.

Instead of barging into cities with rogue taxi services, Uber appears to be stoking enthusiasm with leaders. “Dallas is a perfect location for a program like this,” its mayor, Mike Rawlings, told me last year.

Harsh Reality Check

There is plenty of bad news to temper Uber’s excitement about its flying car dreams. A few days after Moore’s hire was announced, ex-Uber engineer Susan Fowler’s blockbuster blog post about sexual harassment at the company sparked a period of crisis and soul searching that ended in the departure of Travis Kalanick and two board members.

Jeff Holden remained at the company–but he was not unscathed. He helped develop Uber’s controversial 14 “Core Values,” such as “Meritocracy and Toe-Stepping.” Uber’s current CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, called that particular value “an excuse for being an asshole,” in a November 2017 essay which announced that those “Core Values” were being replaced with eight “Cultural Norms.”

But Holden also enjoys a reputation as an articulate forward thinker–something I heard not only from Elevate employees but from a former Uber executive, too.

Silicon Valley has a culture of excusing bad behavior at companies that deliver profits, but Uber isn’t profitable. “You’re in year eight, and you’re losing 4.5 billion dollars,” says the transportation industry expert Horan about the company’s 2017 financial results. “And there’s nothing where you can say, oh yeah, but just give it two years, and they’re there.” Uber doesn’t release detailed financial data, but enough has “dribbled out” for a rough picture, says Horan, who has written exhaustive critiques of the company.

“This company has a long history of playing fast and loose with the numbers, and overpromising and under delivering,” says journalist Steven Hill, author of Raw Deal: How the “Uber Economy” and Runaway Capitalism Are Screwing American Workers.

Uber’s problems, both men say, are due to more than bad management. They stem from an unsustainable core business model that relies on subsidizing fares below cost to undercut competitors.

“Uber has not been able to find a tweak to the taxi business, in order to introduce some new efficiency that would allow them to reach profitability at a price point that is cheaper than the competition,” says Hill.

Nikhil Goel, Elevate’s head of product, says Uber doesn’t subsidize car fares in every city. Holden says Uber’s annual deficit is the result of investment in the company’s growth.

It Takes A Network

Hill and Horan question why Uber is branching into new businesses–not just Elevate but also food delivery, truck dispatching, and more–when it hasn’t yet secured its core market in ground-base taxis. One upshot might be to wring more value from the ride-sharing platform technology Uber has already developed.

“We have a business model, ride sharing, that is exactly the business model that will get [Elevate] off the ground,” says Holden.

Uber has valuable data about how people move around cities, say Uber and its fans in the aviation industry. Meanwhile, Uber’s technology for routing trips and pooling riders can make flights cost effective, the company believes. Uber wants to expand that technology to help manage airplane routing and other aspects of Elevate.

“You can think of it like a new set of web services that connect all the different pieces of the ecosystem and build a real time planning and authorization loop around all of it,” says Holden.

Uber is refraining from taking on many other challenges, like designing airplanes or airports, or training and managing pilots. Instead, it is recruiting companies that already have the necessary expertise, like military and civilian aviation stalwarts Aurora Flight Sciences (part of Boeing) and Bell Helicopter (maker of the V-22 Osprey). Uber is also tapping innovative small players, such as Pipistrel, which has been building electric planes for years.

Distributing responsibility also distributes risk. Uber isn’t paying for plane development that might fail, for instance. Only craft that meet performance and safety requirements, set by Moore’s team, will be allowed on the Elevate network. According to Jeff Holden, plane owners (either manufacturers or companies that buy from them) will get a cut of the revenue–or absorb a portion of the loss–from Elevate’s business.

Still, Uber won’t be doing this on the cheap. Holden declined to specify the budget for Elevate, but concedes it is high. “We’re going to spend a lot of money. It will be a very significant initiative for Uber,” he says.

Some of that money is going to in-house experts who coordinate the partners’ work and get everyone on the same page. As the godfather of electric VTOL, Mark Moore is the linchpin of Elevate. He brings industry credibility–even cult hero status–to a company with no aviation experience and a reputation in sore need of polish. His job is to help aircraft makers negotiate a wide range of concepts into partnerwide consensus on best overall design principles for new kinds of vehicles. And Eric Allison, who now heads up Elevate, actually built an electric VTOL company and functioning plane while he was CEO of Zee.Aero.

Other Uber recruits include Tom Prevot, who spent 20 years at NASA and worked on flight routing systems for unmanned vehicles, which can serve as a template for air taxi management. Stan Swaintek, Elevate’s director of operations, is a former special ops military pilot with a Wharton MBA–a good combination for the militant efficiency Elevate hopes will ensure frequent, full flights.

The Hardest Problems

A big exception to Uber’s technology outsourcing: Battery development. While it won’t build power packs, Uber is developing designs for battery makers to follow. It recruited Celina Mikolajczak, one of Tesla’s top battery developers, to head the work. She joined Elevate in January, becoming the only woman in the senior staff.

Mikolajczak says that today’s batteries are good enough for Uber’s trial flights beginning in 2020–but not for cost-effective commercial flights set to begin three years later.

Related: Meet The Battery Guru Who Will Help Keep Uber’s Sky Taxis Flying

Batteries still pack far less energy per pound than other fuels–something that really hurts the airplanes carrying them. While Mikolajczak helped get Teslas to 300 miles per charge, she’ll have a big challenge getting Elevate’s planes to Uber’s target of 60 miles. Along with needing more capacity, Elevate’s batteries must be capable of a full recharge in 20 minutes or less–and meaningful partial recharging in five–to keep taxis on moneymaking flight schedules.

The stakes are also a lot higher in the air. “If you run out of energy in your automotive battery, you coast to the side of the road and call a tow truck,” says Mikolajczak. “You run out of energy in an aviation battery, that’s a whole different bad day. And that means the redundancy and reliability requirements for an aircraft battery have to be so much bigger.”

However, Uber’s “problem is less about range and more about airspace management and how full are the skies,” believes Bar-Yohay. Uber’s projections, says Eric Allison, are for “mid double-digit thousands” of flights per city per day.

“The current air traffic control system is, the controller talks to anywhere between five and 20 aircraft at any given time, and that’s about as many as you can do as a person,” says Prevot, Uber’s director of engineering for airspace systems. “As we want to operate [Elevate] at scale, we can’t follow the same model.”

If they come to fruition, Elevate planes will fly through different classes of airspace (and encounter everything from drones to Cessnas) in volumes requiring automated management systems that don’t yet truly exist.

Then there’s the question of regulation. “I know from years in the airline industry what it takes to work with the FAA,” says Horan, who claims just a small safety rule change can take years to iron out. Government certification of airplane designs, even traditional ones, is also a multiyear process–years that Elevate’s aggressive schedule scarcely makes room for.

But Elevate’s biggest challenge may be the same that haunts all of Uber: economics.

“All the efficiency gains in aviation have been very long haul, big volumes, big scale,” says Horan. The fewer seats a plane has, the fewer that can go empty for the flight to break even. Elevate planes will likely have just four passenger seats, and a fifth seat will hold a big expense–a certified helicopter pilot. (Since they take off and land like helicopters, VTOLs need pilots with that specific expertise.)

Uber’s goal for air taxis, like road taxis, is to eventually go autonomous. But while they are aggressively pursuing a five-year air taxi rollout plan, Uber and its partners are pretty circumspect about pronouncements around autonomous plane schedules. It seems to be a more cautious stance than Uber’s bullish bet on autonomous cars (another of Jeff Holden’s initiatives), which had a fatal accident in March.

And so Elevate planes will be piloted by humans for the foreseeable future–if Uber can find enough of them. A new study by the University of North Dakota predicts a (rather specific) shortfall of 7,649 helicopter pilots in the U.S. between 2018 and 2036. And regional airlines, also facing a shortage, might pinch even more chopper pilots.

A Big Bet With Little Time

Even if all the technical and logistical problems are solved, it’s not clear that Uber Elevate can turn a profit quickly. And if Uber’s core taxi business keeps sinking, it may pull everything down with it, anyway. “They’ll be out of business in two years, at the rate they’re losing money,” says Steven Hill.

Uber plans to start small, with limited locations where it expects a high volume of potential travelers. In theory, the service will improve as it grows.

“The pricing will start at a higher level, obviously, while the aircraft are more expensive, the operations are less efficient, things are not at scale… autonomy isn’t solved,” says Holden. “It will be a smaller market as a result of that.”

Lacking the efficiencies of scale, but needing to attract customers, will Uber consider subsidizing Elevate fares (as it still does with its car service)? “I’m not going to make a statement on that,” Holden says. “That would be premature.”

It is certainly premature to conclude whether or not Uber can pull off these flying taxi fantasies. Extremely ambitious by design, and burdened by Uber’s corporate baggage, Elevate faces a daunting set of make-or-break challenges. But it is also attracting a tremendous amount of excitement and at least some investment (though it is unclear how much) from people who do understand aviation pretty well.

While not the only air taxi initiative making a play for our sky, Elevate is a monster effort that is adding momentum to the electric VTOL movement. And it is helping to encourage changes in technology and regulation that could live on–even if Uber doesn’t.

This article has been updated with Uber’s estimate of daily air taxi flights per city.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.