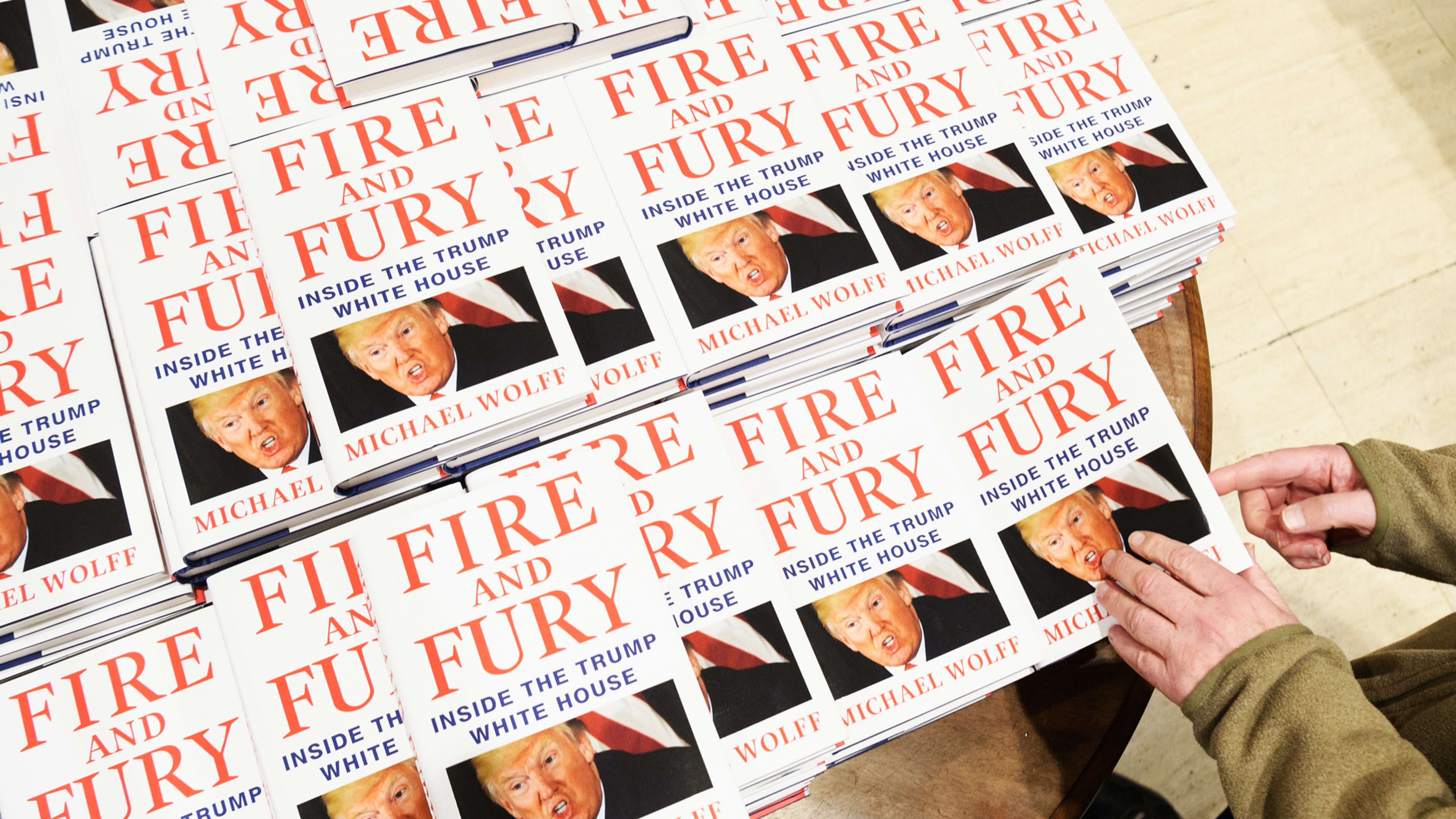

Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury is exploding. Threats of legal action from the Trump White House–the book’s subject–seem only to have poured fuel on the flames. To date, it’s racked up more than a million orders, more than six times the demand that Henry Holt, Fire and Fury’s U.S. publisher, had anticipated, with 29,000 hardcover copies reportedly selling out within two days of the book hitting shelves. Last week’s “bomb cyclone” snow storm delayed restocking shipments in the Northeast. While Macmillan, Henry Holt’s parent company, scrambles to rush out more copies, pirated versions are circulating online.

On its face, an account based on unprecedented access to a figure as divisive as Trump sounds like a runaway hit. But the fact that the book publisher bet much more conservatively on it says a lot about the data problems that still bedevil the book-publishing industry in 2018.

Related: Michael Wolff’s Cattiness Undercuts The Impact Of Fire And Fury

Tomorrow’s Hits And Yesterday’s Habits

As Constance Grady points out at Vox, the book industry’s business model is partly to blame. Like other media sectors (Hollywood, for one), book publishers rely increasingly and overwhelmingly on best-sellers to stay in the black. In addition, an outdated quirk that allows booksellers to return unsold stock to publishers for a full refund incentivizes publishers to keep print runs low. That Fire and Fury’s initial printing was set at 150,000 copies, according to Macmillan CEO John Sargent, was, as Grady notes, a comparative “show of confidence” considering that political nonfiction titles rarely sell more than 100,000 copies–but it hardly signaled an expected blockbuster.

It also matters that Wolff’s sales record is patchy. His previous books have rarely sold more than a few tens of thousands of copies, according to Nielsen BookScan (which, in fairness, sometimes captures well under half of a given title’s actual sales). The book industry’s primary tool for predicting future sales is still to look at an author’s past sales numbers or at the sales numbers of a comparable book. Old-fashioned as it may sound, this remains standard-practice across the industry, making book publishers utterly unprepared for “black swan” events like the sensation that’s erupted over Fire and Fury.

Related: The Fire And Fury Cover Is Hilariously Bad–Here’s A Better One

What Happens When There’s Not Enough Data

A decade after Amazon launched the Kindle, book publishers still earn the majority of their consumer revenue from analog products: hardcovers or paperbacks printed in ink on paper and sold in physical stores. This makes it hard for them to know much about their actual readers; they rely–more than content producers in other industries do–on their own gut instincts to predict what will sell and what won’t.

A key reason is because reading data gleanable from e-books (how many readers complete a book, how quickly they do so, or where they abandon it) is almost exclusively held by the major retail platforms owned by powerful tech companies, including Amazon (Kindle), Apple (iBooks), and Google (Play Books), which categorically do not share it–not even in anonymized or aggregated form–with book publishers. Sales data for e-books is held proprietarily between their publishers and retailers, making digital harder to track than print titles; Nielsen, which collects print sales data from retailers, tries to make up for the difficulty by gathering digital sales data from both retailers and publishers, but its statistical sampling is selective and leaves out most self-published titles.

This data scarcity doesn’t just leave publishers blind to how their readers actually engage with books. It also reinforces behaviors whereby publishers consider booksellers, not readers, to be their actual clients.

And that warps the sales and marketing landscape dramatically. Whereas Netflix knows exactly what each subscriber viewed and can use machine learning to recommend something to watch next–and then develop marketing campaigns based on what the data about which shows are catching–a big publisher like Macmillan does something far different. It launches hundreds of new titles every year, then sends a small swarm of salespeople to bookshops across the country–from tiny indie bookstores to nationwide chains like Barnes & Noble–to brief buyers on what they think will be next season’s hits.

Those sales reps get their briefs not from a finely tuned algorithm but from whatever their editorial teams declare to be their “lead titles.” This affects how both print and digital products get distributed. Publishers rely on bookshop displays and press coverage to get the word out about new books; viral hits like Fire and Fury are the Holy Grail, but it often takes an army of traditional media outlets to crusade for them. As a result of this analog ecosystem, even the question of whether a certain e-book gets featured in Apple’s iBooks store is as much about whose argument wins out when editors and publicists hash it out around a table back at the publisher’s office, as it is about Apple’s own sales data.

Related: How Amazon Is Infiltrating The Physical World

Tending The Old Flame Of Print

Of course, shifting toward more e-books could solve some of this. The same way Netflix knows the exact scene of which episode where you lost interest in The Crown, technology exists (my company Jellybooks builds some of it) to measure reader engagement just as granularly. Yet everything about the digital transition in book publishing is different than what we’ve seen in music, movies, magazines, games, and news media. Many readers still prefer the experience of printed books–their feel, their layout, their smell. (E-books’ market share, while difficult to estimate, is roughly 25% relative to print, and has lately fallen.) Interestingly, this trend is especially pronounced among young readers, while older readers love being able to bump up the font size on their e-readers and tablets.

Publishers like it this way. Bolstering that preference for print means defending the last scrap of ground Amazon hasn’t claimed for itself. The tech giant has enormous market power in e-books and audiobooks (major U.K. and U.S. publishers privately tell me that Amazon accounts for 70–90% of their digital revenue) and much less in print (generally thought to be 10–25% depending on country). Print requires scale and distribution that favor traditional publishers–for now, anyway: Amazon is steadily taking its vast data and logistics into physical bookselling, too. In the meantime, print retains an allure that authors who self-publish haven’t quite replicated on their own.

Until any of this changes, publishers have a strong incentive to defend the moat they’ve dug around themselves. Before the arrival of e-books, Fire and Fury would’ve gone out of print until Henry Holt could rush the next printing to market. Now, disappointed readers can simply download the e-book, which should be good news because it soaks up excess demand. But Macmillan probably isn’t entirely happy about that, since it weakens its market position and makes it even more dependent on Amazon.

What It Will Take To Get More Predictive

The only way forward is for publishers to get to know their actual users better–readers, not bookshops–and change their production methods to be more lean and agile. This is old hat in many other industries but still counts as revolutionary in book publishing (which still sees itself as cultural institution, not just a commercial media operation). Some of this is already underway, at least as baby steps.

My own company has held digital focus groups for publishers (including Macmillan’s corporate siblings in Europe) where we measure how readers engage with a book, whether they finish it, would recommend it, and more–all before it’s ever published. Our tools still work better for fiction, partly because many nonfiction books are purchased but never read, making sales forecasts based on reader engagement tricky. In addition, publishers also make use of various online polls, A/B testing book covers on Facebook, and combing “added to collection” data from social reading networks like Goodreads and LovelyBooks. They also deploy social listening tools on Twitter, Instagram, and elsewhere.

All these tools are getting incrementally better at helping publishers identify which books have the real fire and fury that every editor thinks they feel in their bellies. Whether they and others will ever be widely embraced, though–that’s still hard to predict.

Andrew Rhomberg is the founder and CEO of Jellybooks, a reader analytics and audience insights platform used by book publishers including Penguin Random House, Holtzbrinck (the parent company of Macmillan), Bonnier, Simon & Schuster, Egmont, and others

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.