When husband and wife team Roderick and Randa Milliron founded Interorbital Systems in 1996, it was like many small businesses: A part-time project built on nights and weekends. The one big difference was that their small business designs rockets and build-your-own-satellite kits.

The eight-employee company is now based at the Mojave Air & Spaceport, in the desert town of Mojave, California, just down the highway from Edwards Air Force Base. Its neighbors include other space travel companies like Virgin Galactic, defense multinational BAE Systems, and a host of smaller firms. And Interorbital is currently part of Synergy Moon, one of the five teams competing for the Google Lunar XPRIZE, which will pay $20 million to the first company to land a robot on the moon. (Google extended the deadline from 2014 to 2015, and then eventually to this March, and has said it has no plans to extend it again.)

These smaller and medium-size firms are playing an increasingly crucial role in the space-industrial ecosystem. NASA’s transition to working with private partners like SpaceX, sharply declining costs for rocket launches, and the growth of the do-it-yourself satellite movement mean that it’s easier than ever for space startups to get started. Many entrepreneurs who would have previously launched consumer tech companies or more conventional aerospace firms are now working on space startups, developing everything from propulsion systems to payloads and more.

Last year was stellar for commercial space: According to a recent report from investment firm Space Angels, investors poured a record $3.9 billion into commercial space companies in 2017, a year that included 51 government launches and 37 commercial launches. Over the last eight years, investors and founders have made $25 billion in exits following acquisitions and public offerings, said Space Angels, which counts 303 companies in the space sector globally.

But how does a space company, well, take off?

Pick Your Niche

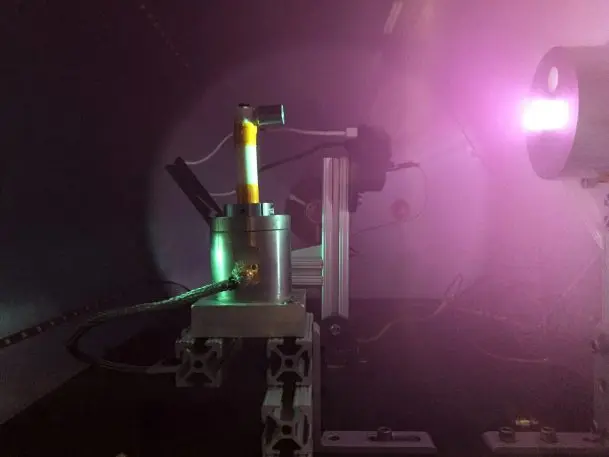

Like many successful startups, a winning space company will find a niche in a market with few competitors. For instance, Phase Four is an El Segundo, California-based startup focused on plasma propulsion systems for satellites.

“Our view of the world is that there are two ways to make money in space,” says CEO Simon Halpern, who previously launched another firm, Aether Industries, which makes technology for high-altitude balloons. “The first is with your payload–your camera or your weather sensor or your antennas, etc.–which are either collecting data or transmitting data or signals. The second thing you need to generate revenue space is putting that payload in the right place at the right time. You can have the absolute best billion-dollar camera or sensor, and if it’s not facing the right location or flying over the right place at the right time of day on Earth, it is a useless piece of technology. We come in on the second part of that.”

Like many space startups, Phase Four is capitalizing on the rise of cubesats, essentially low-cost, miniaturized satellites that can be as small as a shoebox and sent into orbit by the dozen. For instance, Planet and Terra Bella—a company that Google acquired in 2014 and sold to Planet last year—use Cubesats to map and photograph the Earth on a routine basis, on behalf of companies, scientists, and governments.

Think Local, Invest Global

The space action isn’t confined to the U.S. Francois Chopard, the CEO of Starburst, an aviation and aerospace accelerator that offers funding and assistance to early-stage companies, says the privatized nature of the new space race means funding is as likely to come from international investors as from U.S.-based venture capital. “Lots of entrepreneurs are experienced in business, but also fascinated with space,” says Chopard. He’s French and splits his time between Paris and San Francisco; Starburst maintains offices in both locations, as well as in Singapore, Munich, Tel Aviv, São Paulo, Montreal, and Los Angeles. (Masten and Phase Four are among Starburst’s portfolio companies.)

Similarly, while the most prominent players in commercial space may be American, space startups are a global phenomenon. Graham Turnock of the U.K. Space Agency announced this past December that it is helping fund four new space tech incubators, and Saudi Arabia’s public investment fund is investing approximately $1 billion in space firms Virgin Galactic, Virgin Orbit, and The Spaceship Company. In Japan, private space travel firm Ispace has raised approximately $90 million to send a spacecraft into the moon’s orbit by 2019.

Government Help Helps

SpaceX, Boeing, Virgin Galactic, and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin might dominate the headlines with their massive projects, but government grants, funding, and incentives remain the bread and butter of the space tech world.

Take Rocket Lab, a U.S.-New Zealand company working on commercial satellite launches with its own Electron rocket. The company, which aims to manufacture low-cost rockets at a rate of one per week that will sell for approximately $5 million per flight—compared to SpaceX, which charges about $62 million per launch—has approximately 200 employees in the U.S. and New Zealand, where it is conducting its launches.

New Zealand’s eagerness to build up its aerospace credentials and economy has worked to Rocket Lab’s benefit: According to a company representative, Rocket Lab has received around $1.3 million in government grants since 2007 for both research and development projects and student funding. An additional growth grant from Callaghan Innovation, a New Zealand quasi-government organization, means that New Zealand’s government refunds Rocket Lab 20¢ for each dollar Rocket Lab spends on R&D inside of New Zealand. (According to Crunchbase, the company has raised a total of approximately $75 million in funding from blue-chip Silicon Valley firms like Khosla Ventures and Bessemer Venture Partners.)

Although it might be obvious, contracts for government-funded science research can be a significant source of income for many space startups. Phase Four, for instance, received a $950,000 DARPA grant the year they were founded to build a satellite propulsion system. A company spokesperson also says it is receiving undisclosed additional U.S. government funding, but that it isn’t ready to disclose details.

Give Your Business Time To Grow

Much like other startups, stability and growth don’t come overnight for small aerospace companies. The founders of Interorbital spent years working on their company as a part-time labor of love before they were able to work on it full-time.

During their lean early years, Interorbital’s Milliron credits the Pacific Rocket Society, a private hobbyist group with a long history in the aerospace world, with providing critical support and mentor access. When they were getting started, Phase Four received support from Spaceport LA, a Los Angeles-based space enthusiast group.

Phase Four also went through a long growth process where Halpern and his cofounder developed their technology, hired employees, and found funding. Like many startups, they looked for venture capital funding; A seed round was used to hire initial employees and support the company at launch, while a later bridge round was to obtain a satellite and a launch to test their propulsion system in space.

Rocket Lab took time to grow as well. “We’re one of those kind of 10-year successes when you grind seven years and then grow and grow in the last three,” says Peter Beck, the company’s CEO. “Prior to the Electron project, we carved ourselves a name and reputation for doing complicated pieces of aerospace hardware.”

It’s Not (Just) Rocket Science

The space business is complex, difficult work that requires not only top-notch engineering and mathematics chops but expertise in business as well. For Phase Four’s Halpern, who previously attended business school, one early decision was to deliberately seek out investors who are comfortable with the aerospace world.

“I made sure to seek out investors where I don’t have to explain the fundamentals of space,” Halpern says. “We saw that the fastest business development [for satellites] revolves around getting to market quickly. Especially for a venture-funded company, we saw a timeline with venture capital that sometimes doesn’t line up with being a space company.” He adds, “Space tends to take a long time for things to come to fruition.”

At Rocket Lab, Beck says, a third of the company’s focus is devoted to technology, another third to infrastructure, and another to what he calls “regulatory innovation.” The company had to navigate regulatory obstacles unique to both the space travel industry and running a binational aerospace firm. For instance, Beck cites the challenge of bilateral treaties between New Zealand and the U.S. as one specific issue Rocket Lab faced.

All that innovation appeared to pay off this weekend. After a maiden flight last May that failed to reach orbit, Rocket Lab successfully launched the Electron into orbit on January 20, sending several cubesats into space from its New Zealand launch site. “We’re thrilled to reach this milestone so quickly after our first test launch,” Beck said in a statement. “Today marks the beginning of a new era in commercial access to space.” (See a video of the launch above.)

Aerospace startups in general, of course, face one undeniable obstacle for now: It’s still hard to make money from outer space. The history of space travel is filled with smaller companies that didn’t make it. But even those companies that don’t succeed can take solace in knowing that they’re literally going where no startups have gone before.

Read more: The Next Frontier For Ambitious Entrepreneurs

Update: This article has been updated to clarify that Starburst works with early-stage companies across the aviation and aerospace spectrum.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.