Big news for my mom: It turns out my job has a big impact on the entire country.

That’s according to a new political science study published today, which looked at the effect news outlets have on public discourse. While the findings may seem intuitive, this group of scholars—who work at Harvard, M.I.T., and the Florida State University—were able to show that whatever the media chooses to focus on has a profound impact on what people discuss in their everyday lives.

“What we wanted to do,” says Benjamin Schneer, a co-author and political science professor at Florida State University, “was figure out exactly what the effect of the media was on the national conversation.” So the political scientists essentially teamed up with a group of small to medium-sized publications and coordinated coverage at set intervals of time. They then analyzed the social media conversations around those specific topics.

Proving Something That Intuitively Makes Sense

Everyone loves to mock academic studies that prove the obvious, so it should be emphasized that this is no small feat. Historically, it’s proven very difficult for social scientists to quantitively show the media’s effect. “It’s actually really hard to measure how much of an impact the media has,” says Schneer.” For instance, if researchers are merely mapping what people are talking about, they are faced with a chicken versus egg problem. Which is to say, if simply looking at what’s written compares to what people are talking about, it would be nearly impossible to disentangle whether media coverage follows public conversation or vice versa. To circumvent this issue, the team did something quite ingenious: they facilitated their own coverage. Since they created the topics written about, they could then track whether or not this new coverage created heightened social media conversation.

The methodology worked like this: Schneer and his colleagues teamed up with the Media Consortium–a network of independent publications–and recruited nearly 50 publications who agreed to tailor certain coverage around important subjects–including race, the environment, immigration, jobs, abortion, etc. Two to five outlets were told to write about the same subject and even asked to collaborate. The idea was to create a journalistic moment–one outlet may produce a story and another may write a follow-up to it. Or, they may work together on a series of stories focusing on the one subject. All the publications would work together to publicize the work. (Schneer compared these “packets” of coverage to the Paradise Papers.)

The outlets retained complete editorial control over the pieces, so long as they were about the given subject. But the researchers then requested that the articles be very specifically timed for publication. When they gave the green light, the news outlets would publish their stories and the political scientists analyzed all of Twitter to see if people were talking about the subject. They then compared the week the posts were published to a control week when there was no planned coverage of the subject to see if there was an increase in social dialogue.

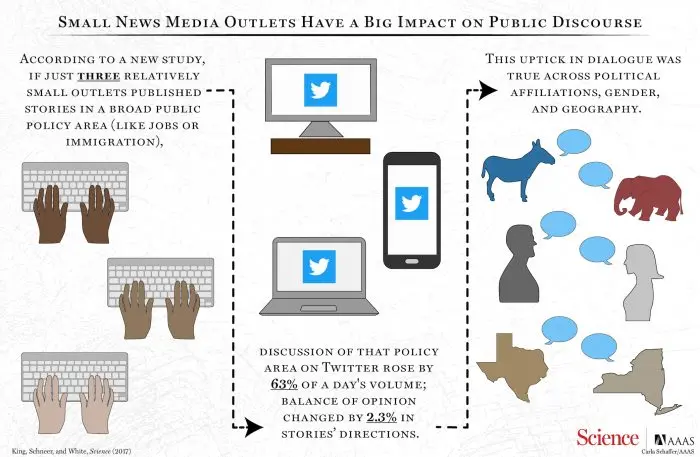

And the findings were impressive: Schneer and his colleagues found that when a cluster of stories was published, the national conversation about that subject–at least on Twitter–increased by about 63%. Which is to say, what the media covers had a profound impact on what Americans are talking about online.

The study took nearly five years to complete. A lot of the time was spent figuring out the precise methodology to definitively demonstrate the hypothesis. And the other big hurdle was getting media companies to agree to tailor coverage for a huge psychology experiment. Creating a way for both journalists and academics to feel OK about the study was “a learning process,” says Schneer.

Frightening Implications

What’s most exciting (or scary)–at least from my journalistic perspective–is the scholarship that could follow from these findings. When the scholars first looked into the media’s impact, terms like “fake news” were completely unheard of. Now, following the 2016 election, questions have surfaced about Russia and other’s impact at social media disinformation campaigns.

The experiments had finished when these issues hit the headlines, yet Schneer realized the importance of the work. There are implications, he says “for fake news.” That is, “a concerted effort by a small number of news sites–that are not even particularly well known–that could have a surprisingly large effect on what people are talking about and thinking about in the national conversation.” If a few small publications focusing their coverage on real issues changed what Americans talked about, imagine what Facebook-focused content farms actually did.

Another, smaller finding from the study bolsters these fears: the orchestrated coverage changed people’s opinions too. Outlets often have opinions or ideological slants in the pieces they write, and Schneer’s team found that the composition of overall readers’ opinions changed with the coverage by 2.3% in the direction of ideological slant of the articles published.

For Schneer, these findings elucidated the current information crisis, as well as the importance of a well-funded and independent media industry. “Since we completed the study, it’s become clearer and clearer that journalism and the media is on everyone’s minds–it’s also clear the role it has to play in our democracy.”

He goes on, “You read or hear about the cuts in newsrooms, journalists losing their jobs, some outlets being shuttered entirely. It makes us think about the change in the composition in the media … to the extent that these [these industry cuts] change the reporting.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.