When Amazon teased its automated convenience store, Amazon Go, late last year, reactions ranged from fascination with the new technology to mortification at AI’s continuing takeover of the workplace. Using machine learning, cameras, and other sensors, Amazon would track what people take off shelves and charge them for what they walk out with—no cashier needed. While Amazon Go has been held up with knotty technical glitches, along stumbled in Bodega, a kiosk startup for convenience items that was instantly despised as an existential threat to corner-store institutions in cities like New York.

Now, into that charged environment steps San Francisco startup Poly, one of several companies developing a camera system and machine-learning models to track shoppers’ purchases. Poly gave Fast Company an exclusive preview of the technology, which is essentially Amazon Go for the rest of retail. The company has signed on one “big chain” retailer for a pilot project, says cofounder Alberto Rizzoli. The client doesn’t want to be named until the pilot begins in the coming months, says Rizzoli, although he mentioned having meetings with 7-Eleven.

For inspiration, Rizzoli looks not just to Silicon Valley but to the Tuscan seashore, where he shopped at stabilimento balenare—seaside bodegas—during family holidays. “What I would do, I would grab a pack of popcorn and I would just show it to the clerk … and she would just write it down on a piece of paper,” he says. At the end of the vacation, Rizzoli settled his tab for popcorn and whatever else he had picked up. “God knows how many lira I got scammed on that,” he says. “[But] there was that ease that made me always rely on that place where I wouldn’t have to queue up.”

Unlike the unmanned stores promised by Amazon (and delivered in China by establishments like BingoBox), Rizzoli claims that Poly will eliminate drudgery, but not whole jobs. “If we do things right, then we can have a system that can actually make anyone starting a business get a lot more ability to interact with their customers,” he says. “And the only thing they don’t do anymore is the checkout part.”

AI Meets Messy Real Life

Getting it right is an enormous technical challenge, however. Amazon, one of the biggest AI companies in the world, had planned to open its first Amazon Go store to the public in early 2017, but it’s been delayed indefinitely by technical glitches (according to the Wall Street Journal). The Seattle behemoth and its tribulations haven’t scared off competitors, though. Santa Clara-based Standard Cognition recently raised $5 million from investors, including Charles River and Y Combinator, to do just what bootstrapped Poly is aiming to do. Rizzoli says he knows of at least one other startup competitor, which is still in stealth mode.

Poly doesn’t have to use facial recognition to put a real name with each face, although that does make checkout much easier, says Rizzoli. His ideal (a model applied in some automated stores in China) would be for shoppers to register for the system, including a photo that the cameras could use to identify customers as they enter and leave the store in order to automatically charge their account. They would also check in to the store with an app. (In China’s Tao Cafe, for instance, this involves scanning a QR code on the phone screen.)

When I pointed out how creepy that could be, Rizzoli acknowledged that some prospective clients also don’t want such a level of tracking. He suggested some workarounds. The system can extract enough information to tell people apart, without having to attach real identities to them. And customers could pay by cash or even credit card, with the promise from Poly that it wouldn’t match that credit card number to the face it’s looking at.

The demo included a large-screen TV displaying what a clerk monitoring the system would see. Our stick-figure renderings on the screen illustrate how Poly extracts meaning from movement. The demo screen labeled activities like standing, eating, drinking, and even dancing, hinting at future uses of the technology.

“We want that to be used in places that are not just products on shelves,” says Rizzoli, “Like how many people are using the coffee machine at a 7-Eleven, or how many people are using the gas pump.” Back in our mini-store, though, the system mainly tracked when either of us reached for a product on a store shelf.

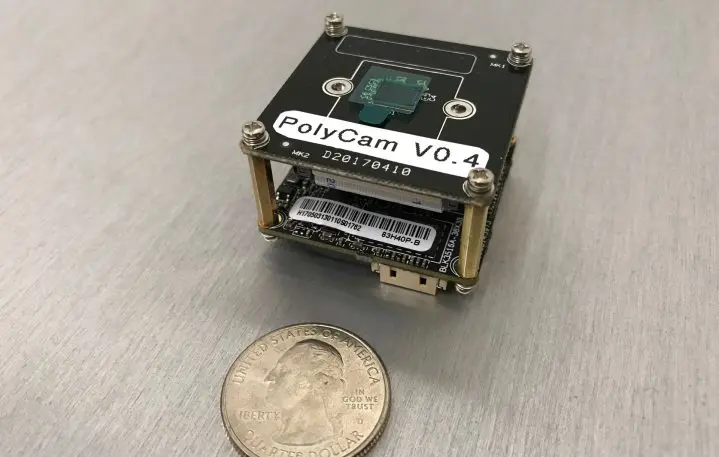

Video feeds are captured by inexpensive cameras that Poly ordered from a Chinese manufacturer, modified with higher-end image sensors. 1080p HD footage at 15 frames per second is enough for training and running the multiple image- and activity-recognition models required. Sending video to the cloud would take far too long, so footage is processed locally on a PC with a single high-end graphics card (a Nvidia 1080Ti, although even lower-end cards can work). That’s a level of efficiency that Rizzoli claims is an advantage over competitors.

“No single model can do all this autonomous market work, so we are actually doing multiple things here,” says Rizzoli. “What’s running here is a combination of different models that are trying to figure out who you are, where you are, what you’re doing, and then ultimately what products you’re using.” Poly has tested its system with up to 23 people (the most that will fit in their little room), and Rizzoli reckons it might be able to handle up to 40. Reports say that Amazon Go ran into difficulty tracking more than 20 people.

Poly’s level of image and activity tracking goes beyond self-checkout. It can function as a store security system, an inventory tracker, and a way to make sure employees aren’t slacking off. Poly also generates heat maps to provide insights on how customers move about the store. And it collects information that could interest marketers—like what products people look at and/or pick up to examine, even if they don’t ultimately buy them.

Self-Checkout 2.0?

Poly struggles with all the challenges you might imagine. It can’t tell what you’ve picked up if you stand with your back to the camera, for instance. It can also get confused if two people stand very close together. In a full implementation, a store will have several cameras mounted up high (what Poly calls “eagles”) to get around obstructions. By the time someone reaches checkout, several cameras would need to have verified the objects the person has picked up before charging them. Tracking gets radically better, says Rizzoli, with cameras, called owls, that are perched on the underside of each shelf, viewing everything on the shelf below. It’s an extra cost, but an important upgrade that Poly will encourage clients to choose.

A very early version of the Owl camera in action.[Animation: courtesy of Poly]Context is also important. The goal isn’t to be able to identify any of the tens of thousands of objects stores carry wherever they may be. Cameras watching the dairy section, for instance, will be looking for things like milk, butter, and yogurt, although Poly can tell if someone puts down an item from another part of the store. “So, we don’t want to say that that’s a piece of porterhouse steak, because that would not always work,” says Rizzoli. “But we know that there’s a piece of red meat in the milk aisle.”

Fresh foods like fruits and vegetables are proving especially tricky and require a lot of model training to take into account the variety of shapes and sizes, as well as occlusion when items are piled together. Identifying multiple items, like someone holding two cans of soda in one hand, is also a significant challenge.

The challenge for any automated market is that if it doesn’t work 100%, it doesn’t work at all. Frustration with current self-checkout systems provides a prime example, yet Poly is trying to do something far more difficult. (One of the most successful automated markets, China’s BingoBox, requires shoppers to scan barcodes on products—which is far easier than requiring 100% image recognition.)

Amazon reportedly learned this lesson when beta testers crowded the store or walked around too quickly. Rizzoli says a system needs to be prepared to handle a whole continuum of possible scenarios—from a “civilized” situation in which people pick up items and move about in an orderly fashion, to an uncivilized one in which people bump into things and items fall off shelves. “In a civilized manner, then we can get 98% of the items in the store recorded,” he says. “If you do that in an uncivilized manner, that can go down to 70%. We’re trying to get the uncivilized situation fully covered.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.