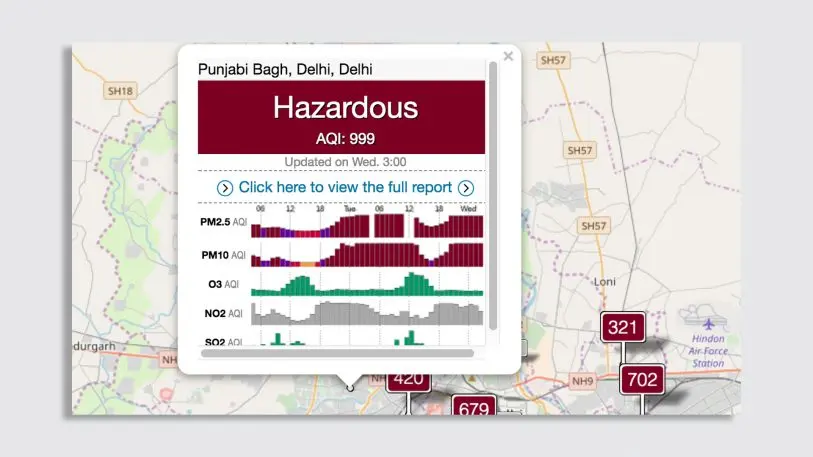

On a particularly smoggy day, when the Air Quality Index (AQI) in a city reaches a value over 300, public health officials consider it an emergency. The AQI is designed to end at 500. This morning, in the New Delhi neighborhood of Punjabi Bagh, the index reached at 999 (or potentially even higher, as some sensors or the reporting website simply may not be set up to deal with AQI levels over 1,000).

The smog has grounded flights, forced the closure of schools through Sunday, and caused a 24 car pile-up on a local highway. It’s not the first time that the air has been this bad in Delhi, which the World Health Organization has previously ranked the most polluted city in the world. Other Indian cities are often equally polluted, leading to serious health problems: Recent data links air pollution in India to the deaths of 1.6 million people in 2016.

But the country is trying to change. “The air pollution issue in India has reached a critical point in that it is causing major respiratory illness, and cities are choking with dirty air,” says Anjali Jaiswal, director of the India Initiative at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council. “So governments are either, one, being forced to act on pollution because of the public outcry and court decisions, or two, cities are moving forward and leading on this.”

On a larger and more visionary scale, India aims to shift to electric cars–that are mostly shared–over the next decade. In the same period of time, it also plans to shift to get nearly 60% of its energy from renewable sources.

“I just went to the largest solar park in the world–1,000 megawatts of solar energy,” says Jaiswal. “When you ask people where [that would be], they don’t think that’s in India. But the Indian government is really moving forward…clean energy really is one of the key solutions for air pollution.”

It’s not a shift that will happen immediately–and studies have found that millions of children living in Delhi already have irreversible lung damage. But progress is beginning, by necessity. “It is a public health crisis,” Jaiswal says. “For India, and other developing economies, in particular, they’re hit harder in terms of GDP and economic growth from air pollution . . . In India, it is in India’s interest, cities’ interest, government interest, to have clean air in order to have productive, healthy societies.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.