In late July, working in the middle of the night, researchers began visiting beaches in Costa Rica with 3D-printed spheres–each roughly the size of a golf ball–designed to look like sea turtle eggs. They buried the decoy eggs in nests along with real eggs, covered their tracks on the beach, and waited. Inside each egg, a GPS device was ready to track the movements of poachers.

It was the first trial of a new system developed by the Nicaragua-based nonprofit Paso Pacifico, which works to protect biodiversity in Central America. Sea turtles are especially at risk from poaching; in Nicaragua, for example, more than 95% of turtle eggs laid on beaches are poached and eaten locally or shipped to cities, where they are sold in bars and restaurants as a delicacy and supposed aphrodisiac. The nonprofit works with community volunteers to protect a handful of beaches, but can’t work everywhere.

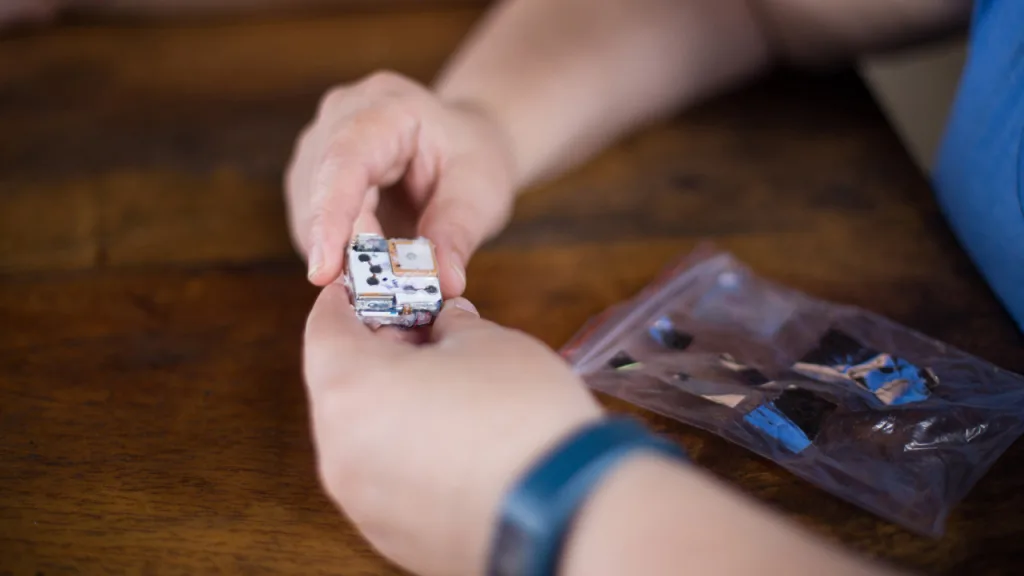

They turned to a 3D printer, which makes it fairly easy to replicate the shape of a sea turtle egg. With the help of a special effects artist from Hollywood, they perfected the right shade of paint and texture to make the egg look realistic. A lightweight GPS tracking device fits inside.

The trackers don’t always work perfectly. In the first trial, which involved planting fake eggs in 44 sea turtle nests, some of the eggs from the nests that were poached may have been consumed locally, where cell-phone reception wasn’t strong enough to follow the signal. But others showed a clear path inland from the beach. The trial also proved that poachers would carry the decoys with them, unable to tell that they weren’t real.

When the nonprofit and others begin to use the eggs in ongoing programs, the data could be shared with governments to aid enforcement of anti-poaching laws, particularly if the trackers show that the eggs are crossing borders and violating international treaties. In other cases–because governments often don’t prioritize protecting the eggs–the data could be used in educational campaigns about the turtles. As poachers become aware of the artificial eggs, that could also serve as a deterrent.

Similar technology has been used to track poaching in other animals, including GPS-implanted fake elephant tusks that helped show how ivory funds African warlords. Paso Pacifico plans to use its approach to track poaching of other animals as well. Traffickers often poach parrot and macaw eggs for the pet trade, for example. “If we could get those trade routes figured out by having artificial parrot eggs, that could be really interesting,” she says.

Now that the group has shown that the devices can work, it’s working on lowering the cost to produce each egg, which are currently made individually. The cost now is more than $100 per egg, but the nonprofit hopes to reduce that to less than $50, so that it can be used by many more conservation nonprofits and governments. “Our goal right now is actually focused on the business model of the project and how to bring it to scale,” Otterstrom says. The group plans to launch the tech within six months.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.