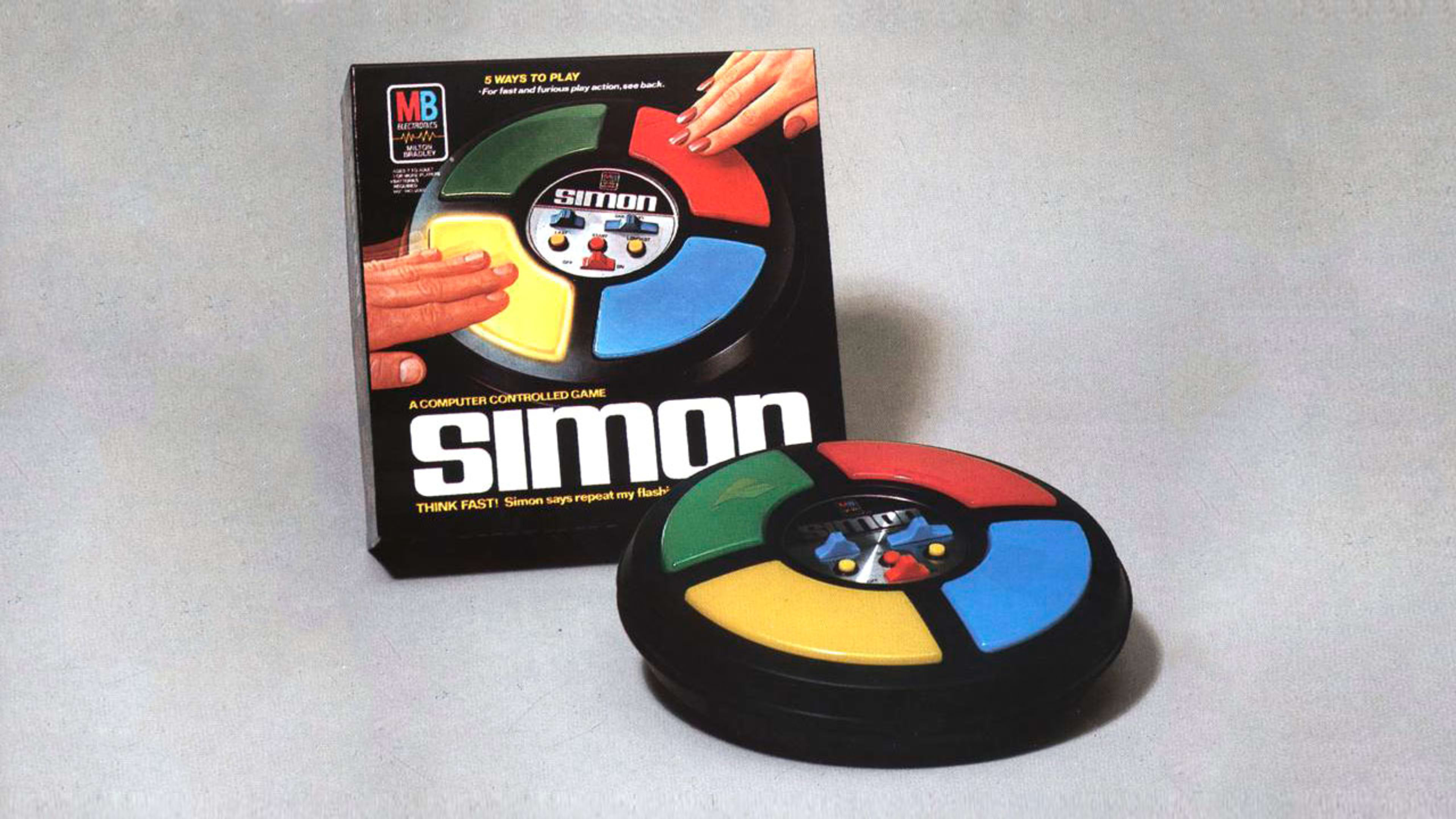

Tech giants Google, Microsoft, and eBay all use blue, yellow, red, and green as their logo colors. But those hues made an indelible mark on consumer tech 40 years ago with a product from Milton Bradley, a board-game company with roots stretching back to the Civil War. The colors differentiated the four wide plastic arcs on the face of an electronic party game called Simon.

Named after the classic children’s game “Simon Says,” the new toy tested players’ memories by making them repeat progressively longer patterns of lights and associated sounds by pressing the four colored buttons. Pressing the wrong button or failing to press one in time yielded an insulting raspberry sound. Simon sold for $25–about $92 in today’s dollars—and became a phenomenon that holiday season.

Despite Simon being protected by a U.S. patent, it soon attracted plenty of competitors. Einstein had an uninspired, rectangular design and a commercial featuring Gong Show mainstay Bill Saluga as “Raymond J. Johnson, Jr.” Atari, creator of the 1974 Touch Me arcade game that inspired Simon’s gameplay, would release a handheld electronic version of that game–its only dedicated handheld–bereft of Simon’s light-show pizzazz. An octogonal offering from Tiger Electronics exuded irony by carrying the name Copycat.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19ywx0KtoMM

Competition also came in the form of electronic toys that included multiple games. These included a pattern-repetition option within Merlin, a Parker Brothers electronic game that looked a bit like a red Motorola MicroTAC cell phone from a decade later. Another was Mego’s Fabulous Fred, a larger 10-in-1 electronic game that featured nine lit multicolored buttons. But by the end of the ’80s, these and other handheld electronic games of the era had vanished from the scene. Simon is the sole survivor.

“Many more complicated games came and went,” notes Randy Klimpert, the current director of design and development for the Simon brand at Hasbro, which acquired Milton Bradley in 1984. “The simplicity of the play and the very basic, spartan elements, I think, are what makes Simon classic and also gives us the opportunity to keep updating it.”

Simon was a multiplayer game from the start. Players would sit around the glowing object centered on a table, like a crystal ball at a seance. But Klimpert says the product’s stationary nature was less of a conscious design decision than it was a limitation of technology at the time: “The original Simon was huge. It wasn’t very portable. It needed four D batteries. It necessarily needed to take up space.”

“With Simon, it’s the core basic gameplay that’s so compelling, but it’s also done in such an attractive package,” says J.P. Dyson, director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games in Rochester, NY. “It’s the lights, the sounds,” He cites Simon’s social aspect as contributing to its early success, comparing it to Pokémon Go versus the virtual reality headset-like isolation that characterized earlier handheld electronic games.

With its circular shape and colored lights, Simon looked like an actual flash in the pan—something that you might assume would quickly go the way of 1975’s Pet Rock. It didn’t turn out that way. Given the go-ahead by Milton Bradley 40 years ago this month, the game was unveiled to the toy industry at the Toy Fair show in February 1978. It was then formally launched the following May at New York’s glitzy nightclub Studio 54 at a party that featured a four-foot Simon floating above the crowd like the saucer from Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Simon was co-invented by Ralph Baer, a pioneering consumer electronics engineer who, after seeing Atari’s conceptually similar Touch Me arcade game, concluded that it had “nice gameplay, terrible execution, visually boring and miserable rasping sounds,” according to his autobiography. He teamed up with Marvin Glass and Associates, a leading toy design company of the era, to produce what was originally intended to be an 8″-by-8″ square toy called Feedback. Baer, who was dubbed the father of videogames for having designed Magnavox’s Odyssey console, had plenty of motivation to one-up Atari: Its success had killed off the Odyssey. But while the videogame market ultimately flourished and the market for dedicated portable electronic games fizzled, Simon has been the most enduring direct descendant of his genius.

That’s because Hasbro has seemed determined to show that there’s been virtually no tech fad that is beyond the bounds of the Simon brand. Beyond slimming the original Simon disc down, shrinking it into a few handheld and even keychain-sized versions, and even releasing a Simon shaped like Darth Vader’s head over the years, Hasbro has fiddled with Simon in more fundamental ways throughout the decades. Indeed, there have been enough Simon mutations to challenge the memory of a Simon champion. Among them:

Super Simon. Introduced by Milton Bradley in 1979, this game abandoned the circular shape of the original to create a rectangle with two sets of four buttons laid out side-by-side like piano keys optimized for head-to-head play. Super Simon’s Decision button would reveal which side had reacted fastest. The main gameplay variation was to replace the ever-increasing sequence with a completely new pattern after every round, making successful repetition much more difficult.

Simon Stix. Modeled after drumsticks but connected by an audio cable, 2004’s Stix represented an early attempt to integrate sensors into Simon and something of a cross between Simon and Bop-It, a sassier, sensor-laden smash-hit toy that Hasbro would also come to acquire. Instead of pressing buttons, players either shook the sticks or crossed them in response to various color flashes set to a beat. The game was criticized for its lack of intuitiveness when compared to the original, and for its use of six AAA batteries.

Simon Trickster. Expanding beyond the core pattern of the original game, 2005’s Trickster upped the ante by adding three main gameplay variations: Simon Bounce, in which the colors jump to different buttons; Simon Surprise, in which every button is the same color, removing a key visual memory cue; and Simon Rewind, in which you had to repeat the pattern in reverse order.

As with the original Simon, Hasbro zapped Simon Trickster with its shrink ray, but the whole idea of Trickster was ultimately abandoned. According to Jennifer Boswinkel, senior director of marketing for the Simon brand at Hasbro, it “stretched the gameplay from the core essence of Simon a bit too far” by straying from the watch-remember-repeat pattern.

Simon Flash. Introduced in 2011, Flash deconstructed the classic Simon disc into four blocks that were reminiscent of Sifteo’s more technologically advanced Cubes. Gameplay variations included Simon Shuffle, in which the cubes had to be rearranged to fit an original color order, and Simon Lights Out, in which players had to keep rearranging the cube into patterns that turned off all lights in a sort of light version of Mastermind. Hasbro also created Flash versions of Yahtzee and Scrabble.

Simon may never have gone away, but it was around 2012, according to Boswinkel, that Hasbro started seriously looking at boosting the brand with gameplay nostalgia and alluring technology in mind. That effort has yielded three more recent variants:

Simon Swipe. As the smartphone advanced us from simple taps to swipes, Simon followed suit. Simon Swipe hollowed out much of the interior of the classic form factor and made the buttons swipeable. Now, in addition to remembering the order of color flashes, players had to remember which direction to swipe across the surface for certain steps. Unlike the original disc, Simon Swipe was not meant to be used on a table. “When we did Swipe,” says Klimpert, “we made it more pass-around from the insight that people want to gather and play together.”

Simon Air. Moving Simon into a vertical orientation, Air removed a key element of previous Simon games, making contact with the buttons. Instead, players replicated patterns by placing their hand near a light. The dynamic is a bit like musical instruments that play canned samples such as Beamz. (Mattel would also get in on the sonic, motion-activated vertical structure with a game called Loopz.) According to Boswinkel, the idea behind Air was to get people up and active and using their hands in a new way.

Air also introduced something new to Simon: collaborative play rather than competition. “You could play all four colors at once and you need four hands because we wanted to make sure it wasn’t just a solo experience to beat my own score,” notes Boswinkel. “You could bring in your dad, your mom, your brother, your sister, and your friends and challenge them to how well you can repeat the pattern back [together].”

Simon Optix. Styled after an augmented reality headset, the latest reinvention of the game is Hasbro’s first wearable Simon. (The company had previously licensed the Simon name to Nelsonic for a Simon wristwatch). The $20 Optix flashes lights in front of your eyes. Patterns are repeated by waving your hands in front of the visor. Like Simon Air but unlike traditional Simon gameplay, Optix allows two colors to light up at the same time. The toy is available in a two-pack that allows individual players to compete or collaborate literally head-to-head; Hasbro says that the practical limit of headsets that can be synced up is 15.

Regardless of the form factor, Simon has in the past few years found its most powerful competitor: mobile games. Both the iOS app store and Google Play have a number of cheap or free pattern-repeating apps that show up in results for the search term “Simon,” some of which closely mimic Milton Bradley’s original 1978 aesthetic. While competition from videogames has been a broad issue for the toy industry for years, it would seem particularly threatening to Simon, considering that its core electronic gameplay is ridiculously simple by today’s standards. And with games like Optix and Air eschewing tactile contact, some recent Simon games would appear to give up a satisfying differentiator. (Many an early Simon incurred physical abuse at the palms of those frustrated by its honking raspberry sound effect.)

Klimpert says that the key appeal of the Simon experience versus smartphone gaming is that the former is about face-to-face gaming: “You’re really bringing people together with the play whether you’re doing it sequentially or at the same time.” Simon fans need not fret about its viability in the short term, as Boswinkel says the current products are “performing great.”

As for this holiday season, the three most recent Simon offshoots will be offered alongside what Hasbro calls Simon Classic. Debuting last year in response to popular demand, it’s a slimmer, less power-hungry version of the disc that started it all offering an experience close to what made Simon a hit in 1978. Sometimes, history repeats itself. And sometimes, we do the repeating.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.