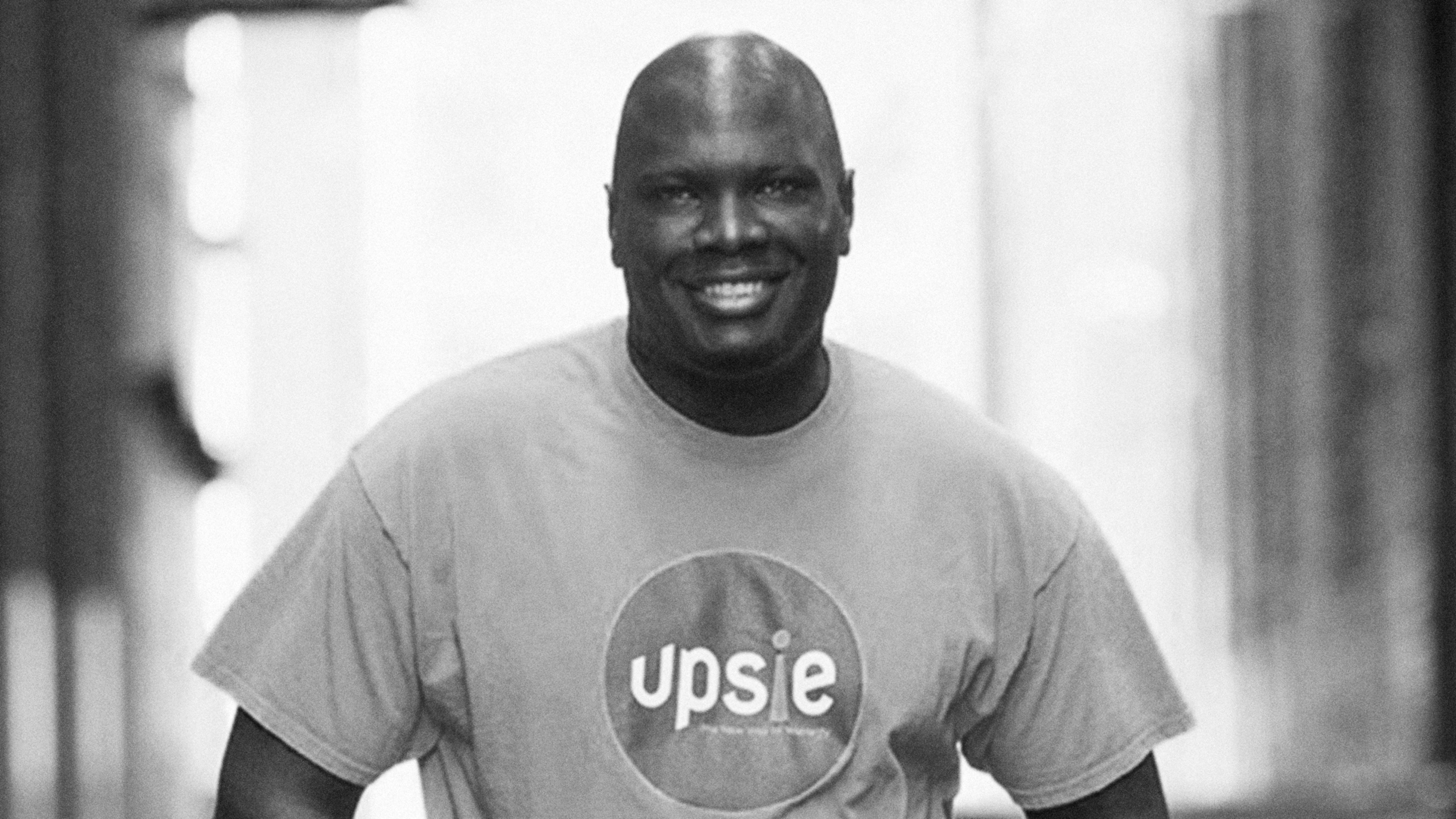

Clarence Bethea doesn’t have the standard background for a tech entrepreneur. He didn’t go to Stanford or drop out of Harvard like Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates. He doesn’t live in San Francisco or Boston. He’s black. And his childhood wasn’t easy: His dad used to come home drunk or high at night and beat his mom, right in front of him.

In his teens, Bethea sold drugs on the street in Atlanta. “I was a kid who did what he had to do to make money,” he says now. “If it was drugs, it didn’t matter. It was only through the grace of God that I met the people I did and it changed my life. By 18, I should have been dead or in jail.”

Related: Why Venture Capitalists Aren’t Funding The Businesses We Need

But, despite this, it’s not hard to imagine Upsie being a bigger company by now. It’s raised $1.5 million in angel funding–not a huge amount in the modern scheme of things. And Bethea has had enough experience with the venture capital community to wonder if he’s been discriminated against. He doesn’t fit the “pattern” that venture capitalists normally invest in.

Not long ago, Bethea says he met with a well-known venture capital firm that was interested in investing in Upsie. The firm did its due diligence and gave Bethea an outline agreement worth $2.5 million. It started looking for other investors to join the round. But then the VCs found out about his past, including that Bethea had been been arrested for a misdemeanor when he was 15. The investors pulled out of the deal, even though Bethea is now in his late-30s and married with a kid.

“They got nervous about it for some reason and there was nothing I could do about it,” Bethea tells Fast Company. “I don’t think the misdemeanor had anything to do with it. It’s more that I’m a black man in tech. I don’t come from the traditional background and there’s a lack of education [among VCs] about the value that someone like myself can bring to the table.”

Related: New Report Reveals Just How Badly Black Women-Led Startups Are Being Underfunded

In 2015, just 1% of funding of U.S venture capital went to African Americans or Latinos. Only 5% went to female founders. More than 75% went to companies based in just three states: Massachusetts, New York, and California. Graduates of Stanford, Harvard, Berkeley, MIT, NYU, and the University of Pennsylvania received 10% of all the world’s startup financing.

This partly explains why entrepreneurial opportunities are shrinking. Though we live in a time when startups are feted across political and social divides, the rate of new business creation is actually down compared to previous generations. It’s therefore not surprising that Bethea has struggled to raise money. A lot of people beyond the coasts and beyond the tech categories that VCs favor often struggle. Critics say VCs look for certain types of people–white, elite-educated, in their 20s or 30s–and certain businesses. They invest in social signals and pre-worn patterns, rather than character and socially useful ideas.

Upsie, for instance, sells extended warranties (also known as service contracts or protection policies) online. It promises substantial price cuts compared to retailer policies and offers its own repair service and guarantees. For example, a two-year policy with accidental coverage for a Samsung Galaxy S8 64GB phone costs $79.99 with a $75 deductible on Upsie. With Best Buy, the same coverage costs $199.99, with a $199 deductible. (Upsie gets its name from being the opposite of a oopsie, or a poor decision). Plus, says Bethea, Upsie offers greater convenience. When there’s a problem with your phone, you can check into an online account and look up your policy instead of having to hunt down a paper receipt.

At the moment, a substantial amount of what you pay to insure a phone, TV, or washing machine is retained by the company selling the warranty rather than being paid out in claims. Best Buy, for example, generated $830 million in warranty commissions in the year to January 2016, its accounts show. That was only about 2% of its overall revenues, but more than 60% of its operating profits.

Upsie simply makes a smaller margin on each warranty it sells–that’s how it undercuts the prices of other companies. Bethea approvingly quotes Jeff Bezos’s famous line that “Your margin is my opportunity.”

“We are in an old, archaic industry that is not up on new technology and the customer,” Bethea says. “For years, it’s been about the retailer making money. The opportunity is in winning consumers and empowering them to control their experience.”

Bethea argues that many customers are hard-sold at checkout time into buying policies they don’t understand. They don’t appreciate what is and what isn’t covered and that there may be cheaper options available if they looked around. Indeed, groups like Consumer Reports recommend avoiding extended warranties altogether for many goods, because they often don’t make financial sense.

“The retailers are, quite frankly, greedy,” Bethea says. “We think the value we offer to our customers is convenience, transparency, and price cuts.” Upsie is definitely on to something. The question is whether Bethea can win the financing and wider startup support to follow through on its promise.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.