Anthony Pegues sat at a white table inside one of tech school General Assembly’s Manhattan classrooms, hunched over his silver laptop. He was still grappling with the previous night’s homework in the final moments before his class would begin.

Pegues last worked as a part-time janitor at a middle school in New Rochelle, a few miles north of New York City. But this past March he found himself at General Assembly, halfway through a program called Code Bridge. The 17-week coding bootcamp is a partnership between General Assembly, an unaccredited for-profit education center that has garnered $120 million in venture funding, and the decades-old nonprofit Bronx learning institution Per Scholas. Per Scholas prepares students for five weeks before sending them into General Assembly’s challenging full stack web development course.

This experience was the first formal coding training Pegues had ever received.

“My goal is to get a decent job, you know, make this my career,” Pegues tells me, looking at the whiteboard in front of us as if he sees something written there about his future. He turns his face and flashes me a beaming smile, his eyebrows raise far into his forehead. “Get out on my own and experience more of life.”

Little did he know back then that by the end of the year, he would become one of Code Bridge’s poster-boy success stories.

The near-mythic biographies of business titans like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg have led many inside and outside Silicon Valley to believe that diplomas aren’t a requirement for working in America’s booming tech sector. Indeed, Google’s former SVP of people operations, Laszlo Bock, has said as many as 14% of the company’s teams can be comprised of people who never graduated college.

But it doesn’t seem like this laissez-faire attitude toward conventional educational credentials has made entry into companies like Twitter and Google any easier for people who have historically been left out of America’s technology sector: women and people of color–especially black, Latinx, and Native American workers. Less than 4% of the workforces at Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo are black, even though 13.3% of United States citizens identify as black or African-American (that percentage is probably higher, but the U.S. census does not break out how many Americans identify as black and another race).

While many organizations have cropped up to solve the so-called tech pipeline issue, few are as narrowly focused on employment as Code Bridge. CodeBridge is still, to be sure, a very small project, but it has an important mission: to make sure underprivileged Americans don’t continue to be left out of, arguably, the most important economy in the country–one that regularly doles out six-figure salaries even for entry-level employees.

Pegues graduated high school with a 0.67 grade point average, hardly the kind of track record that typically garners one access to any college with a decent computer science, design, or business program. Back then, Pegues was far more interested in punts and passes than in academics.

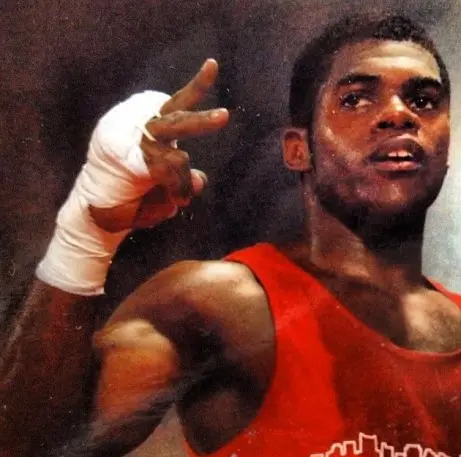

Still trying to capture the elusive athletic greatness for which he believed he was destined, Pegues decided to get into boxing. Though his football career hadn’t panned out, Pegues started shaping up and became adept at jabs and uppercuts. In a few short years, he was winning tournaments and even secured a spot at the Golden Gloves state championship in 2011. When he won the title that year at Madison Square Garden, it was the first time he had ever set foot in the famed arena–despite growing up a short 30-minute drive away.

It may seem obvious that excelling in sports will not necessarily provide a pathway out of poverty, but many high school students remain stuck to the idea that athletic success will make them socially mobile. How could they not? The optics are blaring. Though not the highest earners in the U.S., top athletes garner eye-popping salaries and tons of publicity.

The reality is, only a small fraction of high school athletes compete in college sports–especially on a full-ride scholarship. Even fewer high school athletes go pro.

For black students, the perception is even more complicated because their representation on football and basketball teams is disproportionately high. A University of Pennsylvania study conducted between 2007 and 2010 found that at the college level, black men made up 57.1% of football teams and 64.3% of basketball teams, even though they only represented 2.8% of overall college attendees.

But sometime in 2012, when he was 24, coding caught Pegues’s eye just as mobile apps were becoming fiercely popular. That’s when tried to teach himself some Xcode.

This was the crux of his problem. With little opportunity for upward mobility, Pegues was living at home with his mom at her one-bedroom apartment in a public housing facility. Most nights, he slept on the floor.

But in 2015, something important happened: Thanks to his brief boxing career, Pegues was accepted into a program called the Kilimanjaro Initiative, an opportunity for young people in the U.S. and Africa who have used the study of martial arts to overcome adversity. Every year the organization shepherds a cohort through an experience-building climb up Mt. Kilimanjaro’s rocky slopes. As they hiked the alpine desert, Pegues’s troupe shared with one another their personal histories and the challenges they still faced. High above the clouds, Pegues had an opportunity to talk about the difficulties in his life, growing up with a single mother who struggled to provide for her family while his father was in and out of prison.

“If I show you it,” Pegues says to me seriously, “it’s straight garbage.” He breaks into a smile, and we laugh. His experience reflects an overall problem with massive open online courses like Udemy and Coursera, which were once expected to upend college as we know it. It turns out online learning isn’t always the best way to learn a new skill. Still, Pegue says, the app was impressive enough that Kilimanjaro’s cofounder, Brion Bonkowski, asked Pegues to volunteer as a technology manager and brand ambassador for the Initiative. “That was something I could put on my resume. At the time, I didn’t even have a resume,” Pegues recalls.

Pegues didn’t stop there. While working with Kilimanjaro, Pegues applied for General Assembly’s Opportunity Fund, a sponsored scholarship. The Opportunity Fund only offers a small number of grants every year. Pegues didn’t get it, but someone at General Assembly recommended he try out for the Code Bridge pilot through Per Scholas. He was accepted.

“There is way more talent in New York City than we are able to train,” says Per Scholas managing director Kelly Richardson. “We could easily scale much more than we’re at right now. It’s just a matter of resources.” The school currently accepts about 20% of applicants across all its programs, which range from entry-level IT training to CompTIA certifications.

Per Scholas is located in a beige building cut into a grid by a series of brown borders, far uptown from the upscale Flatiron neighborhood where General Assembly has set up shop. The entrance to Per Scholas, an unlabeled glass door, is hidden between a substance abuse clinic and a pharmacy.

The industrial eastern side of the Bronx, where Per Scholas has made its home, is an entire universe away from San Francisco’s Market Street corridor, where sidewalks abound with white men casually chatting about venture capital rounds. In the Bronx, tech startups are scant and many of the people scattered on the streets can more adeptly discuss the finer points of scraping together a livable income from low-wage work and state subsidies than how to manage their next million dollar deal. Median household incomes for the area hover around $24,000 and 40% of residents live below the poverty line.

It is here that Per Scholas teaches adults the ins and outs of cybersecurity, network engineering, and quality assurance–often with curricula that are partially devised by a corporate partner like Barclay’s or Cisco.

Considering that they were coming in typically with an eighth-grade reading or eighth-grade math level, it’s pretty amazing,” says Richardson. While many organizations are trying to close the digital divide with K-12 STEM education programs or internships for high school and college students, Per Scholas exclusively reskills adults who have little technical experience–people who are often overlooked–and doesn’t charge tuition.

Part of Per Scholas’s success with its less technologically-experienced constituents lies in its abilities to assess applicants’ motivation to learn and identify environmental issues that might affect their success. That’s why the face-to-face interview is one of the most important pieces of an application to any Per Scholas program, including Code Bridge. Magnardo Tavarez, a manager and technical instructor at Per Scholas, says that since people who apply to Code Bridge aren’t usually already highly technical, he looks for other attributes, like an inclination to obsess over subjects of interest or a proclivity for problem solving.

“If you are at home messing around with turntables and teaching yourself how to build your own audio,” says Tavarez, “I can teach you.”

Ayala’s growing interest in graphic design, which sprouted while she worked at the Bronx Museum, is what ultimately caused her to seek out Per Scholas. Shortly after finishing the Code Bridge program, Ayala landed a position as an email marketing coordinator at the subscription pet supply service BarkBox, a startup valued at well over $250 million dollars. Her role is a blend of her experience: part coding, part marketing, a far cry from the entry-level customer service jobs Tech Bridge graduates generally secure. “Seventeen weeks of training and my salary has more than doubled,” she says.

Ayala’s history demonstrated not only the tenacity Tavarez looks for during interviews, but also proved that she had the necessary support system in place. When she was accepted into the Code Bridge program, Ayala lived near the Bronx Zoo with her grandmother, brother, and mother, who works as a bus driver. Generally, Per Scholas likes to know that applicants will have stable housing and access to regular meals while they’re in the Code Bridge session.

Once students join Code Bridge, Per Scholas offers them access to a career coach, a financial advisor, and a social worker. In addition, the organization continues to support students while they’re at General Assembly. In fact, Code Bridge graduates are welcome to use Per Scholas as a work space or chat with its advisors for the next two years. Some Code Bridge students have even returned to the program as teaching assistants. The school has a strict attendance policy–you can’t be late to class more than two times without getting kicked out–but students who don’t complete the program are always welcome to join another session.

“There are not a lot programs, period, that offer full student support” beyond the classroom, says Anna Wintroub, director of social innovation at AT&T, which provided funding for the Code Bridge pilot. “We are really excited about what the pilot has already yielded and the opportunities for scaling beyond the work that has happened thus far,” she adds.

Back in his class at General Assembly, Pegues still has not figured out last night’s homework. “I’m trying to figure out what these errors are,” he says, pointing at the screen. His assignment was to build the ability to comment on a blog post. He had already created a blog and the ability to create posts, but coding a commenting tool was proving difficult for him.

Nevertheless, he believes he can do it. “The instructors are cool and they deliver the information we need the way we need it. Everybody learns differently, but everybody helps each other out,” Pegues says.

Throughout the classrooms, desks were littered with Macbooks and mason jars filled with water. At the front of the room was an instructor named “Tims” whose mess of sandy hair gave him the look of a young Bill Gates. He was teaching a lesson on making associations in a database so they can be called up by the software the students are building.

“I see people frowning at their screens,” Tims says, a little smirk curling from his lips. As Tims teaches, Pegues peppers him with questions without raising a hand–and occasionally finishes Tims’ sentences, mostly to himself as a way of letting the lessons sink into his brain.

During breaks, Pegues is the first to seek out other classmates for help. He is also the first to offer it when new concepts weren’t catching on for others.

Amid chatter about the homework and their home lives, one student shakes his head and comments on how sleepy he was. He doesn’t drink coffee, he says. “I do push-ups to wake up.” Next thing I knew, he was on the floor–and soon Pegues joined him, pumping out push-ups for a rush of adrenaline. “He’s like the coolest,” another student named Brian said to me, pointing at Pegues.

For Schwartz, Per Scholas and CodeBridge may also represent an opportunity to test an idea he has long mulled over–a new model for funding education.

“We need to have some other mechanism for paying for it,” Schwartz comments, referring to the U.S. higher education system. “[It should be] neither the individual through cash or debt and, I think, ideally not the government,” he goes on.

What Schwartz believes the best model could be is one where companies front cash for students’ educational expenses in exchange for a predetermined number of paid employees each year.

“We’re going to train candidates who are ultimately going to have the skill sets that employers want to hire for,” says Schwartz. Rather than paying for recruiting and onboarding, companies would pay for training. Such a system would not only save students from going into debt, it could also allow for more a diverse set of candidates.

Schwartz is still a long way from revising education as we know it, however. To get there, he and Per Scholas will have to prove to employers that the quality of Code Bridge candidates is as good as or better than the applicant pool from which those employers currently recruit. For now, Code Bridge is largely funded through donations and public grants raised by both Per Scholas and General Assembly. The program costs the two organizations about $21,000 per student for the full 17-week program–plus the cost of two years’ worth of alumni resources.

Top tech firms have been known to funnel money into a variety of inclusion and diversity initiatives in the hopes that they can attract a wide range of experiences to their companies–it’s widely understood that diverse workforces spur new ideas and innovation. Twitter, for example, has committed to recruiting some of its employees at annual conferences held by Grace Hopper, the National Society of Black Engineers, and Hispanic Professional Engineers. Companies like Google, Facebook, and Airbnb have forged partnerships with organizations that hook black and Latinx undergraduates and graduates into their company internships.

Despite these efforts, none of the larger tech companies have been able to meaningfully raise the percentages of underrepresented minorities working in their ranks, according to data released by the companies themselves. Code Bridge, and new bridge programs that Per Scholas might spin up with other coding academies, may not cure all that ails the Valley–and it is still a very small initiative. Even so, it is a compelling option for companies looking to to create more opportunities for people of color–especially people with “diverse backgrounds” (i.e., students who didn’t grow up in a financially secure household or attend Stanford and Yale).

Though the CodeBridge program is, for now, unique to New York, there is plenty of room for growth. Per Scholas has schools in Ohio, Georgia, Dallas, and near the nation’s capital. General Assembly has institutions scattered both around the country and abroad.

On graduation day, General Assembly held a special ceremony for Code Bridge students. Chairs were placed in rows and a podium was set up in a large communal lounge. Pegues’s long hours of struggle paid off when he was selected as the class’s valedictorian. In his speech to his classmates, he reminisces about the four months they had spent together.

“Brian, never compare yourself to others and keep pushing yourself to do your best,” Pegues says to the group. “Jenny, keep finding that challenge, find that beautiful struggle.”

“Guys, I don’t know where we’re going, but I know we’re on our way,” Pegues concludes. The room erupted in woots and applause.

When I met up with Pegues almost two months after graduation, he still had not found a job, but he was confident that one was going to come through. He had a fair number of interviews and a lot of inbound interest. He had set a goal to get a job by the end of May, but nothing came through. “I guess I wasn’t as faithful in that goal that I set. So the next time around I said, it to happen. This is it. And it really is it,” he says.

Not long after that, he ran into an old coworker from Isaac Young. “I told him, man, I got an offer!” Pegues says, smiling. Pegues hopes that his story can inspire others like his old workmate, who is a little bit younger than Pegues. Already, Pegues says, he has gotten this friend to make healthier life decisions, to stop smoking weed and eat better.

“He’s seen the journey,” says Pegues shrugging. “We just talked for like an hour and a half and I was like whatever you want to do–just do it.”

The reality is that at this moment in time Pegues is still the exception and not the rule. There are still many potential tech workers out there, people who are overlooked for technology sector opportunities because they are viewed as untrainable. Code Bridge hopes to suspend that stereotype. The next batch of students began their program this past Monday.

Save

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.