By the numbers, the messaging app Kik looks like a runaway success: 15 million monthly active users, and $200 million in venture funding at a valuation that puts it in the unicorn club. And yet all those numbers pale in comparison to Facebook Messenger’s 1 billion users, or even WeChat’s 938 million.

Kik’s founder, the Canadian whiz kid Ted Livingston, had dreams of making it the “WeChat of the West.” But Livingston eventually realized that it would be impossible to compete against tech giants willing to lose money on free products just to grab every last bit of user data they could get. And so, rather than raise more VC money to keep his business going, last month Kik did something altogether different: It sold nearly $100 million worth of Kin, a new currency of its own invention built on the Ethereum blockchain.

The pitch to Kik’s backers? To create a self-sustaining messaging app economy that doesn’t depend on advertising. If Kik’s model pans out, it might herald an entirely new funding model for startups that doesn’t just depend on VC cash. Instead, there might be a way for millions of users to buy into the success of a startup they love—and help fund it in the process.

Crushed By Google And Facebook

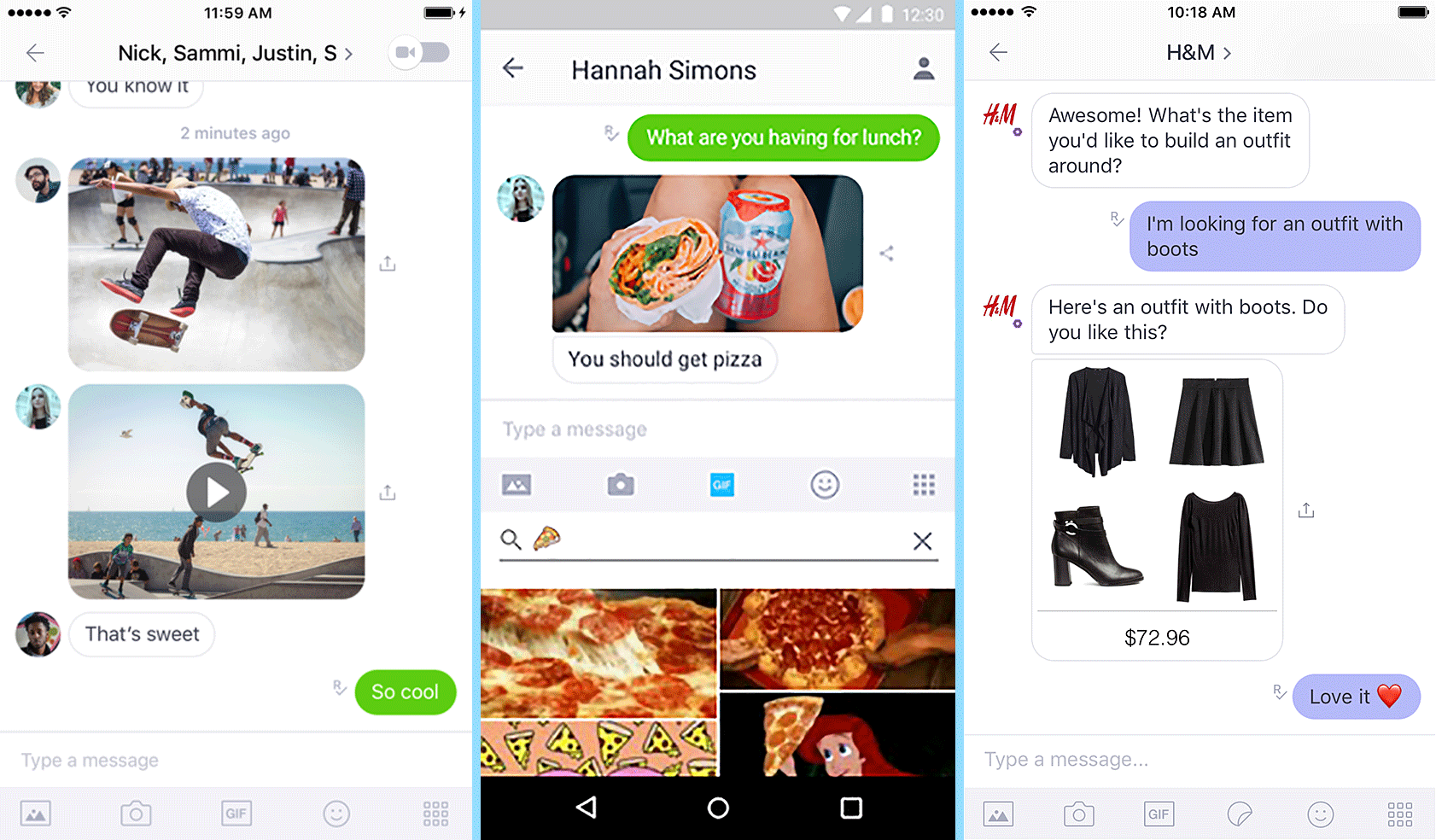

Livingston has an uncanny knack for anticipating tech trends. That talent has kept Kik afloat. The platform grew from a 2009 streaming music service for RIM’s Blackberry phone, into the first chat app that let Blackberry users message friends with iPhones. It then morphed into the first chat app to allow companies to create bots. He realized that chat would become the central organizing app of our digital lives, and early on created a way for outside developers to create mini apps that operate inside the chat experience.

The moment he knew Kik’s existing funding model was doomed, says Livingston, was the day Snapchat filed the paperwork to go public. The filings revealed that Snapchat’s user growth was starting to level off. Snapchat was the darling of the investor community, in part because it had played the game so well. The game was: Keep on taking VC cash until you can build enough scale to compete with Facebook and Google for advertising dollars.

Livingston’s broader worry is that in a world where the best apps are free and supported by ads, Facebook and Google will always be too large and powerful for anyone else to compete. Startups can’t survive without a new business model. As he recently wrote, “These forces could lead to a future of less choice, less innovation, and ultimately, less freedom. We need a better solution.”

That solution was Kin.

How A Cryptocurrency Works

When Bitcoin first appeared in 2011, Livingston realized that digital currencies weren’t just a way to safely move capital online. Rather, they had something no digital good had ever had before: Scarcity.

The reason gold holds its value is that no one can make more of it. The key feature of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is that only a fixed amount will ever be created. Not all of it goes into circulation at once; rather, a reserve is gradually released over time. (With Bitcoin, “mining” is the mechanism for shaking loose uncirculated currency; anyone can mine Bitcoin by dedicating computers to perform an arduous calculation that’s analogous to playing the lottery. The more computer resources you dedicate, the more likely you are to discover Bitcoins.)

Livingston was quick to see that as more and more people used Bitcoin, the more people would want Bitcoin, and the more valuable Bitcoin would become. But he also saw a major flaw: Most people using it were drug dealers or hackers. Unless you’re doing something sketchy, it doesn’t make sense to convert real money into Bitcoin. So even while the value of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is increasing, it’s stemming from pure speculation rather than actual economic value being created by the people who use it.

Livingston realized that one way to solve this problem would be to make cryptocurrency the method of trade inside of Kik, for buying stickers or playing games. The basic engine of value creation is simple: If people actually use Kin, its value goes up. Getting them to use it means creating things they want to buy; creating things people want to buy means incentivizing developers to dream up fun stuff. And Kik has a clever solution for enticing developers: If someone creates a popular new app or virtual good, they get Kin. The more popular their creation is, the more Kin they get. Unlike Bitcoin, where anyone can mine uncirculated Bitcoins, the only way to mine Kin is to make cool stuff.

Last month, Kik sold almost 1 trillion Kin tokens to around 10,000 people. Those tokens represent only 10% of the total supply of Kin. The company also set aside 30% for itself, so that it might sell some to fund its own operations or offer selectively to boost developer activity. The remaining 60% will be doled out to developers by the so-called Rewards Engine, administered by the newly created Kin Foundation.

As for users, they might also earn Kin by generating content for others to see, which they get tipped for, or perhaps even hosting “VIP groups” if they’re high profile enough. The goal is for Kin to align the interests of everyone using Kik. Developers will be rewarded for creating great apps; users will have a way to purchase goods and services while keeping Kik ad-free. And Kik itself benefits only if the system sees vibrant user activity.

Will New Empires Form?

We’re in a frothy moment for cryptocurrencies: So far in 2017, various cryptocurrencies have raised an astounding $2.7 billion through initial coin offerings like Kin’s; there were $700 million just last month alone. But Livingston argues that the froth will create the next great tech innovation. He points out that the dotcom boom was filled with a rash of speculation, but also yielded bedrock companies of a new economy such as eBay and Amazon. “Crypto will be like that,” Livingston says. “99% of these currencies will eventually be worth very little. But a few will have as much impact as Amazon or Google did.”

But even that analogy is not totally apt. Google and Amazon were built atop the infrastructure of the internet, whose protocols didn’t make anyone rich. By contrast, a new cryptocurrency is the infrastructure on which you can build apps and empires. Livingston’s biggest hope is that Kin becomes not only useful for Kik users, but also a means of exchange for entirely new apps beyond Kik that he can’t imagine. The promise of cryptocurrency is to make building infrastructure into a money-making engine that benefits everyone who built it.

Of course, it’s not clear how the competitive landscape may play out. In the future, there might be one or two cryptocurrencies that everyone uses. There might also be thousands that are readily exchanged for each other, thanks to the ease of digital transactions and blockchain ledgers, which are the means by which cryptocurrency transactions are verified and recorded.

Ultimately, the ones that do succeed will have to clear the same hurdles that every great technology company was built upon: trust, ease of use, and consumer demand. To date, cryptocurrencies are hardly user friendly. Livingston wants Kin to be simpler to set up and use inside of Kik than any cryptocurrency before. His own prototype was Kik Points, a basic currency that Kik launched in 2014 to test out whether people really would spend points on the things they want. Just in that test alone, the transaction volumes were three times higher than Bitcoin’s.

The Biggest Problems: Trust and Demand

The greater challenges will be in keeping Kik from becoming a black market and actually getting people to use the currency. Kik itself has sometimes attracted shady behavior. Because users can sign up for the service anonymously, it has become an unwitting host for criminals trading child porn. Kik has responded by increasing its community vetting. With Kin, Kik says that those who buy tokens must do far more to verify their identity than any other cryptocurrency. Kik is also setting aside $10 million to develop moderation tools and new safety features—the analogy there would be the laws that we use to govern cash transactions today.

The problem with many cryptocurrencies today is that they’re simply being hoarded by speculators. Why spend them if their value is going up 1,000% a year? But if no one uses them, then they can’t be used to unlock any economic value. For Kik, there’s a tricky balance to achieve: Developers have to create stuff cool enough that users will spend their Kin on even though it’s appreciating.

“We think we have a good answer for that,” says Livingston. “It’s actually pretty simple. Think about it. What would someone have to do to convince you to spend $5 today?”

I offered a few guesses. Perhaps goods that could only be bought for a limited amount of time? Or maybe goods that could somehow always be resold for what you paid for them? Or maybe currency with some kind of shelf life that demanded it be spent? Livingston demurred.

“Maybe,” he said. “You’ll see soon.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.