As autonomous vehicles have gone from a glimmer in some distant future to a very real feature of our existence, it’s undeniable that not too far from now AVs will be as commonplace as their human-piloted counterparts–and eventually overtake them. This means cities stand at a crossroads: They can either let AVs slowly and chaotically take over their cities, as regular cars did 100 years ago. Or they can make a concrete plan, using the technological features of AVs to reshape transit in a city, eliminating parking and street space used for private cars, and increasing space for pedestrians and bikes–while making all travel more equitable.

While most estimates of AV adoption fall in the range of 20 to 40 years from now, already, manufacturers from Ford to Tesla, alongside tech giants like Google and Uber, are neck-and-neck in the race to bring self-driving cars into the mainstream. Volvo has partnered with Uber to develop self-driving taxis; Ford is teaming up with Lyft to roll out a fleet of autonomous ride-sharing vehicles; Helsinki and Las Vegas have both piloted self-driving buses.

Naturally, the swift ascendance of self-driving cars has urban planners in a tizzy. In June, urbanists Antonio Gomez-Palacio and Alan Boniface wrote in Fast Company that autonomous vehicles have the potential to humanize cities by amplifying the number of shared rides, reducing the need for parking, and making room for more people-friendly infrastructure like parks and bike lanes. But to get to that point, cities will have to make a concerted effort to plan accordingly, starting now.

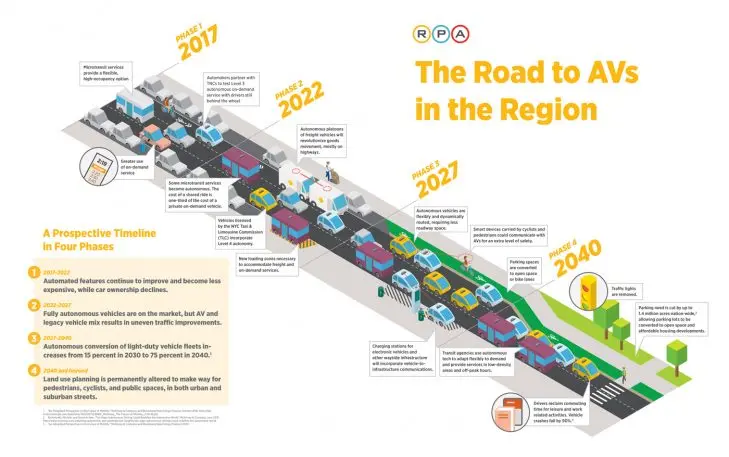

That’s exactly what the Regional Plan Association, the New York metropolitan area urban research and advocacy organization, is aiming to do with the release of its latest report, New Mobility: Autonomous Vehicles and the Region. The RPA releases a strategic plan for the region’s development every 30 or so years; it’s preparing to release its fourth regional plan in November, and the considerations in the New Mobility report proved pressing enough to merit their own document. New Mobility, says Richard Barone, RPA’s vice president for transportation, “is more of a think piece” than a definitive blueprint for what’s to come. “We still don’t know what to expect,” Barone says–but it’s intended to approach this second wave of the automobile with forethought and consideration, and avoid the mistakes cities made when cars became widespread after World War II.

In the last century, Barone says, New York City and the surrounding area essentially let the automobile take over. The groundwork was laid early: In the 1930s, Robert Moses proposed the Belt Parkway and building out a network of highways to slice through the entire metropolitan area, and major urban streets like Fifth Avenue were widened to accommodate more traffic as far back as 1908. On-street parking grew to take over 24 square miles of the city, and the boom in private cars and taxis came to function as an alternative to the region’s sprawling mass transit system.

But that dynamic has landed the New York area with a host of issues. The roads are clogged with cars at peak hours, and pedestrians and cyclists are starved for space. As cities look to curb their carbon emissions, continuing to prioritize cars in urban places is more and more of a problem.

With the advent of autonomous vehicles, Barone says, the region has an opportunity to integrate the technology into the existing mass transit system, and have them function more as an extension of the infrastructure, instead of allowing it to spawn independently. “Rather than repeat the mistakes of the last automobile age, adaptation should intentionally use AV technology to improve the reach, utility, and lower the cost of public transportation,” Barone writes in the report.

To do this, the city will need to adopt a number of policies that encourage the use of autonomous vehicles as a ride-sharing option, but de-incentivize their use as single-occupancy vehicles. These include volume and pricing measures like vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) fees or higher tolls to discourage congestion, and a cap to the overall number of autonomous vehicles allowed during certain times of day or in more congested parts of the city (not dissimilar to air traffic control).

The infrastructure would also have a role to play: By creating more “complete streets” with separated bike and bus lanes, wider pedestrian sidewalks, and designated loading zones for freight and passenger drop-off, the city could limit the number of lanes available to cars. This will, of course, require drastically lowering the volume of on-street parking. This strategy mirrors one undertaken by Oslo, Norway, where, instead of banning cars outright, the city removed on-street parking to make driving more of an annoyance than a convenience.

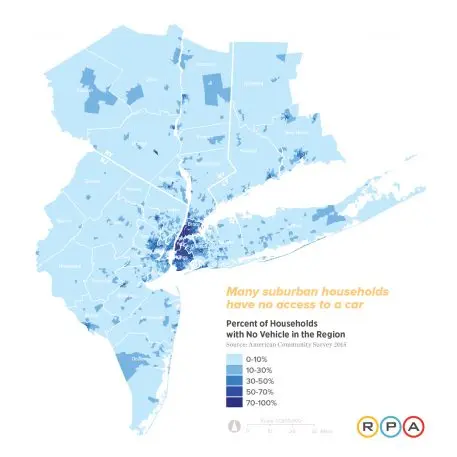

Completely eliminating cars is not the point here. Barone sees great potential for AVs to work in concert with the New York City subway, and with suburban transit options like Metro North and the Long Island Railroad. For some parts of the city, and particularly the suburbs, there is not enough density or demand to support the extension of mass transit into those areas. Barone envisions a region-wide system that could connect on-demand AVs with mass transit to provide shared rides to those harder-to-reach areas, as a sort of “microtransit” option; this will be especially beneficial to the elderly and disabled, he adds.

Successfully integrating AVs with regional transit systems will require private vehicle manufacturers and ride-sharing companies (like the Lyft-Ford union) to work collaboratively with the local government and transportation department. For example, ride-share options could be synced with train schedules to be available to collect people disembarking the train and transport them to their final destination; perhaps a payment-transfer system could even be implemented. Because the ride shares will be autonomous, the companies will not have to worry about paying a driver to complete this service.

Keeping the use of AVs equitable will also be a major consideration for cities. In order to ensure equity of use across all socioeconomic levels in the region, it’ll be important for the city to implement a subsidy scheme for low-income people who want to make use of AV ride sharing. Fees collected through the congestion pricing schemes and tolls could go toward easing the cost of AV rides for qualifying people, and governments should implement policies that ensure against discrimination by location–charging more for trips to distant or lower-income areas, for example. There’s also another, potentially exciting way that the integration of AVs could, over time, boost affordability in cities: By making more room for affordable housing. As cities do away with parking lots, there will be a lot of space for subsidized housing developments.

These are major shifts, Barone admits, and the region will have to be careful to ensure no one gets lost in the shuffle. That includes drivers currently employed by taxi and ride-sharing companies; federal, state, and local governments, along with private-sector manufacturers and ride-sharing companies, should start working together now to develop a scheme to transition these employees to other roles.

One thing is for certain, though: For the sake of both sustainability and sanity, New York–and other metropolitan regions around the world–cannot afford to let the AV boom simply add to car congestion. It’s on AV manufacturers to ensure that their cars leave as little a carbon footprint as possible, and it’s beholden to local governments to integrate this innovation so that it allows cities to grow in ways that are cooperative with existing transit systems, and ultimately more beneficial to the people that live there.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.