In the immediate wake of two of the deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history, Americans stare at the aftermath and wonder why. Again, we ask why, and how do we keep this from happening again?

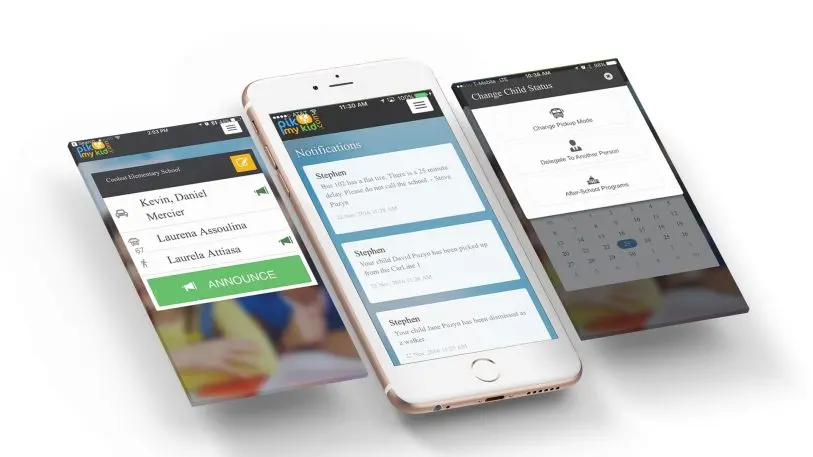

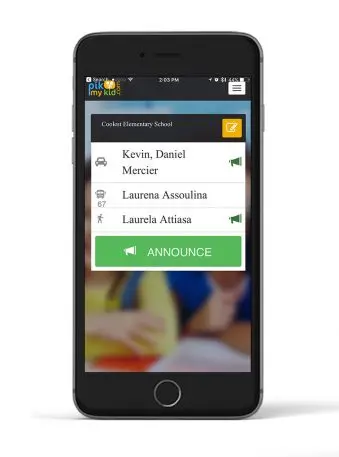

Amid inaction around gun reform or mental health policy, an increasing number of American schools are turning to technology to prepare for, and possibly prevent, shootings. “We have so much to do,” says Pat Bhava, the CEO and founder of PikMyKid, a four-year-old Tampa-based startup that helps parents and teachers track students during and after pickup times. Earlier this year, the startup added a new feature to its app aimed at keeping kids safe during emergencies like an active shooter: a panic button that allows school employees to quickly notify first responders of their location, and send them blueprints of school buildings.

Initially, PikMyKid was focused on addressing the chaos of end-of-day dismissals: by showing where parents or caregivers are parked in a school pickup line, the company says it can shorten the time it takes to pick up children, and help schools make certain that the right kid is getting in the right car. Bhava, who is Indian, said he got the idea after his daughter’s school “put a white girl in the car.”

As the app began managing the traffic flow in and out of schools, Bhava discovered another problem school administrators faced. “They needed to cut down the reaction time from when an [active shooter] incident happens to when the first responders and the entire school swings into an action plan,” he said.

The app’s new feature offers teachers and staff a panic button: when a school employee spots a threat, they press a button within the PikMyKid app. Once the alert is triggered, the real-time location info of the device is sent to 911 and to other important contacts. The app activates the phone’s microphone too, sending a continuous audio signal to emergency responders. Schools pay between $3,000 and $4,000 per year to operate the system, depending upon the size of the school and other options; Bhava says it’s now in use at about 110 schools across 24 states and 3 different countries.

Like other apps that offer digital panic buttons, including Rave Mobile Safety and SchoolGuard, PikMyKid is also adding support for digital maps so that first responders don’t enter classrooms or hallways blind. In July, the startup signed a partnership with FacilityONE, a company that makes interactive, digital blueprints. Currently, most schools’ architectural plans aren’t digitized, but instead kept as hard copies at courthouses or municipal archives. After FacilityONE maps a school, PikMyKid loads the blueprint into the school’s safety profile. “As [first-responders are] approaching any school for any emergency, they are able to pull up these blueprints right from the [PikMyKid] portal,” Bhava says.

A similar mapping system for emergency responders is being implemented at over 25 high schools in Ocean County, California, at a cost of about $800 per floor, county prosecutor Joseph Coronato told USA Today in August. Emergency planning firm Critical Response Group and defense and security company BAE Systems, which make the system, say it could also be deployed in courthouses, hospitals, power plants, places of worship, and theme parks.

Schools are also turning to the kind of shot-detection technologies currently in use on the streets of cities like New York, Chicago, and San Diego. Multiple companies install and maintain the systems, which use sensors to triangulate gunshots and relay information to administrators and first responders. But the hardware and the subscription service it requires can be expensive, costing between $10,000 and $100,000 to install and maintain.

More schools are adopting high-tech security systems, which rely on locked vestibules, card access doors, networked visitor management, and video surveillance.

“As important as keeping intruders out of a school building, is how to respond effectively to safeguard building occupants should the threat gain entry into the building,” said John LaPlaca, founder and president of Altaris Consulting Group, a consultancy that specializes in school safety and that has worked with PikMyKid. “Keep in mind that history has also demonstrated repeatedly that the threat may lawfully be in your building, as has been the case with student or employee shooters.”

To protect schools from more imminent threats, schools are also installing electronic panic systems that can automatically keep occupants behind locked doors within a building, LaPlaca said in an email. In addition to panic button apps, schools are also installing VoIP phone systems that allow staff members to implement a lockdown using a typed-in code if they identify an imminent threat.

Such systems can automatically play pre-recorded messages over building PA systems, notify police, close and lock doors, activate strobes on the building exterior and send text messages to school administrators. But, LaPlaca said, it’s important to remember that no system can be completely impervious to threats. “The grim reality remains that a person who is intent on gaining entry to a school will do so with relative ease, regardless of security measures that are in place,” he said.

Can AI Prevent Shootings Before They Start?

Bhava is quick to admit the greater problem is how to stop shootings before they start. Right now, he said PikMyKid’s focus is “trying to react to a situation in a time-efficient manner,” but prevention “is what we want to get to.” Helping prevent shootings in real-time “is where I see [machine learning] and AI being really helpful, but not in the tools we actually use to manage and track.”

Could data and artificial intelligence help? Machine learning can use existing data to develop algorithms that reveal commonalities: For example, by compiling attacker profiles, machine learning could tell us that both Heath High School-shooter Michael Carneal and Sandy Hook-killer Adam Lanza were bullied in school. AI could then cross-reference this commonality with currently bullied students in order to pinpoint who might become a shooter in the future.

Of course, not every child who’s bullied becomes a mass murderer. And not every mass murderer used to be bullied. Using predictive technology this way could lay the groundwork for a Minority Report-like society. Plus, pattern matching results would likely be wrong: There is no single factor or universal profile for school shooters, no common race, no single gender, no sole family dynamic that AI can latch onto. But that doesn’t mean AI developers can’t search for solutions in the data that they have.

At PikMyKid, most data comes from geotracking. The startup’s pickup feature currently creates a 300-500 yard geofence around partner schools; that’s how administrators know where parents are parked. In the future, Bhava said, “We want to give school administrators access to openly available social feeds within the geofence area around the school–say 5 mi around the school–of any hashtags that involve schools and certain keywords.”

In addition to the obvious, like “bully” or “gun,” violent keywords and phrases are identified by natural language processing (NLP), a type of AI that teaches computers how to understand and use language like people. Twitter’s API makes it easy for developers to access and monitor tweets. But language is tricky–laced with double meanings–so processing those tweets is much harder. Take song lyrics, for example, which commonly show up in posts. “I got a pocketful of bullets and a blueprint of the school” could be the tweet of a future shooter, someone quoting Alice Cooper’s “Wicked Young Man,” or both.

Dr. Desmond Patton, director of Columbia University’s social-media focused SAFE Lab, said, “We only use words as a piece of data, not the whole truth. It’s really important, particularly when we’re talking about social media and data that comes from marginalized groups … The way in which they talk about themselves in their communities is immediately thought of as being risky or being threatening, so we do a lot of work to unpack the narrative behind the narrative. So if a lyric … look[s] aggressive to the untrained eye, we do a lot of work to make sure we unpack the true narrative.”

For four years, the SAFE Lab, a research initiative at the Columbia School of Social Work, has worked with NLP to better understand the language of violence. Human reviewers in the lab use machine learning to process two million tweets posted by 9,000 at-risk youth and gang members and attempt to interpret them: How does language change as a teen gets closer and closer to becoming violent?

“Problematic content can evolve over time,” Patton said. In other words, no one is born a shooter. And perhaps that’s what makes it so hard for AI to predict when someone will become one: No single incident moves a person from full-of-potential to mass-murderer overnight. The process of becoming a killer is gradual, and along the way many at-risk reach out for help.

To identify how youth communicate these changes in their lives, SAFE Lab also analyzes any pictures posted with the tweets. By processing words and images together, Patton said the lab moves beyond simple sentiment analysis–a type of NLP that detects whether language is positive or negative–to focus on “the actual emotionality of an image. Is this image about grief? Is this image about threats?…Is this in a neighborhood? Is this on a street? What else is happening in an image that helps us understand more complexly?”

Related: Why Facial-Recognition Technology Can Be So Biased

As indicators arise, human reviewers at SAFE Lab watch the streams. The data they discover goes to computer scientists at Columbia’s Data Science Institute who quantitatively analyze it, forming subsets to train a machine learning engine to recognize when someone’s at their breaking point. In the event SAFE Lab identifies a threat of violence on social media, the lab can notify social workers in the user’s hometown who are empowered to intervene.

In analyzing social media for violence-related language, SAFE Lab’s algorithm is 81.5% accurate when tested against training data, Patton said. But even with these results, Patton is slow to say AI will one day catch every emerging shooter. “I think there’s this huge focus on what AI can do,” he said. “What we have learned is that AI can’t do it by itself, that AI needs discursive and textual analysis to be able to understand context.”

In other words, even when platforms like PikMyKid integrate keyword alerts, without human review those keywords could trigger false alarms. Or, as Bhava mentions, AI could also find so much threatening language online that officials might get jaded from would-be shooters “crying wolf.”

But AI might also help mitigate that problem, according to Bhava. “That’s where we see AI and machine language really comes and helps us to analyze and crunch those numbers and to reduce false positives to such an extent that the administrators really pay attention to those,” he said. “Because if you flood them with 20-50 messages every day, they get numb to it and overlook real threats which are emerging.”

Related: The Big Business Of Police Tech

In the short term, limited school budgets and the high costs of technology mean that protecting schools from active shooters may depend less on technological solutions and more on basic planning, said LaPlaca, the school safety consultant.

“Technology is not a panacea for creating a safer school,” he said. “Engaging in prevention and threat assessment programs, creating rock-solid emergency plans and conducting ongoing training are the low hanging fruit that can provide tremendous returns for limited or no investment. Many of the most effective improvement opportunities cost nothing at all.”

Terena Bell (@TerenaBell) is a freelance journalist who writes about tech, entertainment, and public affairs.

With additional reporting by Alex Pasternack

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.