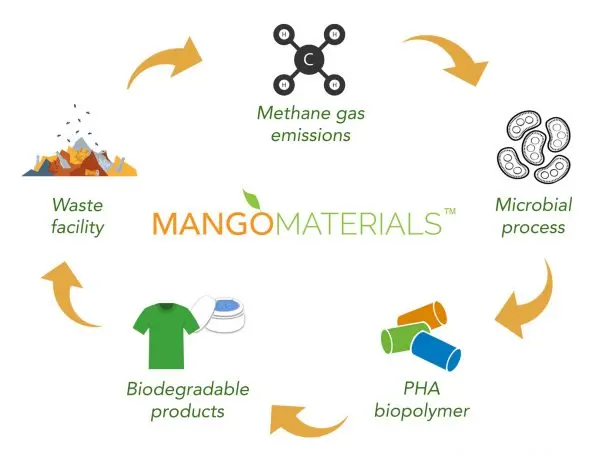

When it wafts from landfills or dairy farms, waste methane–a greenhouse gas 30 times more potent than CO2–is usually seen as a problem. A startup called Mango Materials sees it as a something that can be used to make your next T-shirt or carpet for your house–and then recycled in a closed loop.

“Instead of using ancient fossil carbons to make materials, you’re using something that you already have,” says Molly Morse, CEO of Mango Materials.

At a pilot facility located at a wastewater treatment plant in Redwood City, California, the company is using waste methane to feed bacteria that can produce fully biodegradable bio-polyester fibers. When the bacteria consume methane, they produce PHAs, a kind of plastic that can then be spun into thread. The startup announced the new material at the SynBioBeta conference in San Francisco today.

The material can also reduce ocean plastic pollution. If a T-shirt made from regular polyester is washed in a washing machine, tiny microfibers typically wash down the drain, and because they aren’t broken down at wastewater treatment plants, can make it into the ocean. Fibers from the new material would degrade at a treatment plant instead, and if a whole T-shirt happened to fall in the ocean, marine organisms could digest it.

A handful of apparel and textile companies are testing the product now, and the startup is raising money to scale up to full production. Ultimately, brands that produce clothing with the material could take clothing back when consumers are done and produce something new. PHAs can also be used to make packaging and other plastic-based goods, but the company is focused for now on the garment industry.

“I think that’s an interesting solution that really allows you to have a closed-loop process,” says Morse.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.