In a backyard in the Paris suburb of Montreuil, one couple is taking part in an experiment: A new tiny house in their garden will become home to a series of refugees.

The project, called In My Backyard or IMBY, helps refugees who have a residence permit–but don’t yet feel like part of French society–connect with their French hosts as they get assistance in finding jobs and permanent homes. “People need to have networks other than just other refugees,” Romain Minod, an architect with the French nonprofit Quartorze, which created the project, tells Fast Company. Refugee housing is often isolated from existing neighborhoods; IMBY aims to bring refugees in close contact with people they might not otherwise have met.

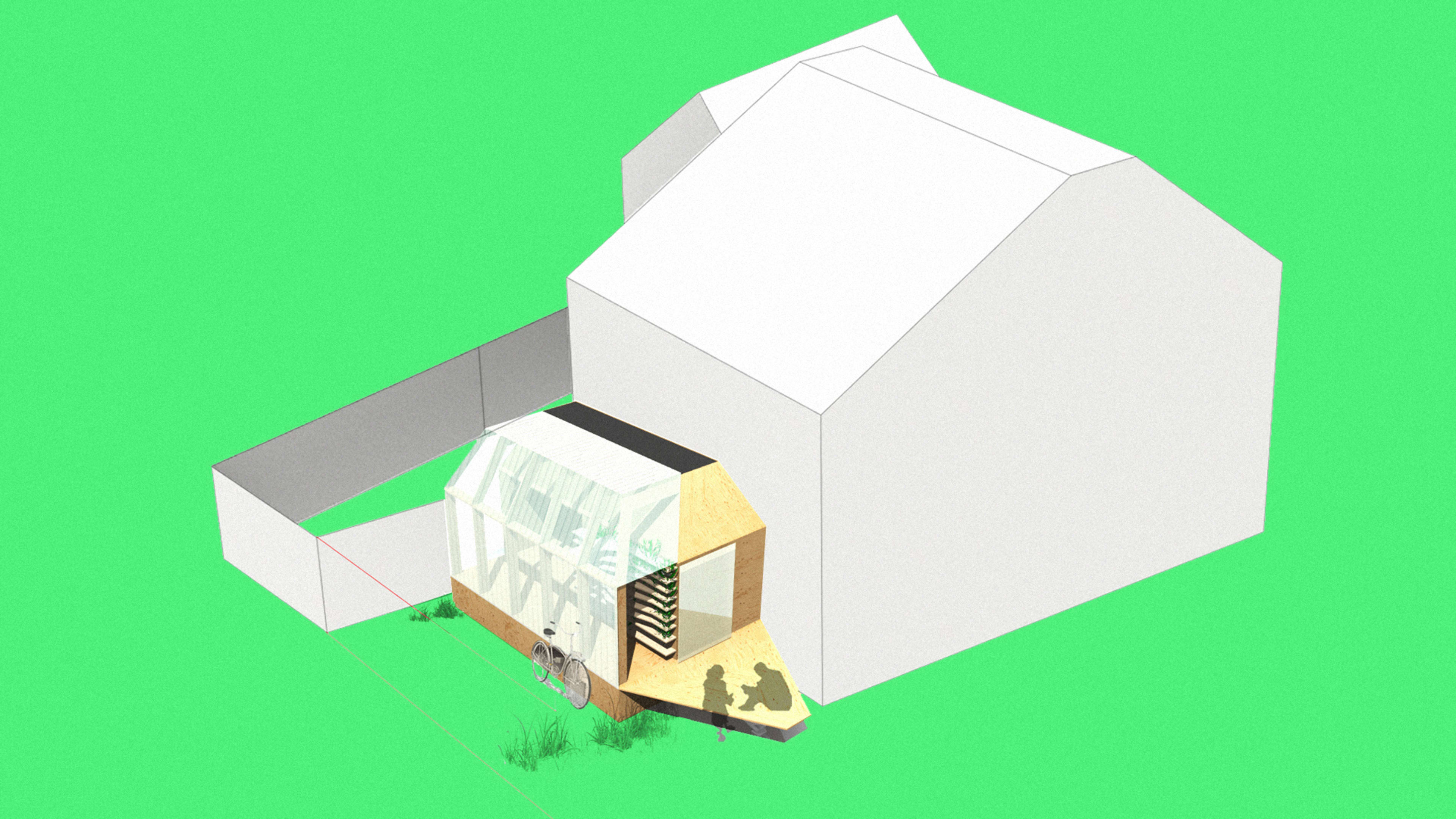

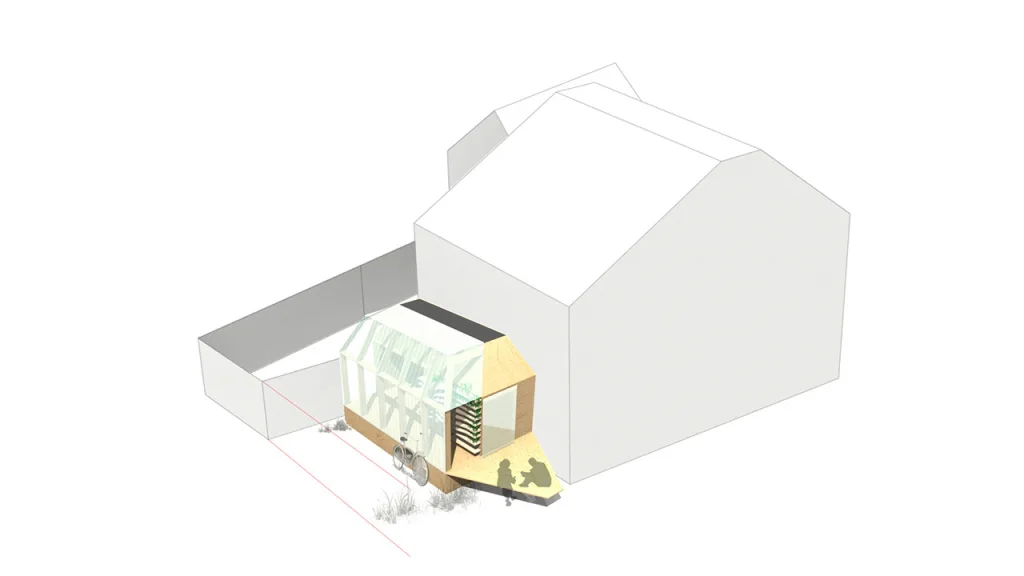

With a size smaller than 215 square feet–under the limit that would require a building permit–the first version of the house, with a kitchen, bathroom, and living room, is large enough for two refugees. Homeowners agree to keep the tiny house for at least two years, at which point they can sign on for another two years, buy the house from the nonprofit to help financially support the program, or let it be dismantled and rebuilt in someone else’s backyard. Refugees are expected to stay six months; if they aren’t ready to leave at that point, they can stay, or another couple can take their place.

While refugees live in the house, they will work closely with social workers to find work and an apartment, while getting government financial support and healthcare. But they’ll also get extra support from their new neighbors. “When you’re living in a building with other people, you’re treated as a number,” says Minod. “But when you’re living with someone else trying to help you in finding jobs . . . I’m pretty sure it’s better for people.”

The tiny house is designed with prefab wooden modules that can be configured based on the layout of a specific backyard. The organization plans to eventually use the assembly as a training program for refugees, who will do the construction themselves. The first home in Montreuil, which will begin construction this month, will be built by a group of volunteers–half refugees, and half citizens–from France and Germany. The social work agency partnering on the project will help select the first refugees who will stay.

That’s a tiny fraction of the number of housing units needed for refugees in France. Two thousand refugees and migrants were moved to temporary shelters from Paris streets in July–some of them likely came from the squalid Calais Jungle refugee camp, which evicted thousands of refugees in October 2016. The UN Refugee Agency estimates that currently 20,000 additional places in shelters are needed for asylum seekers. But if the IMBY model works, the organization plans to share the open-source designs widely so that others can replicate it at a larger scale.

The design could also potentially be used in the U.S., where cities like Portland and Los Angeles are beginning to encourage homeowners to install backyard houses to shelter homeless people.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.