In the St. Clair neighborhood in Pittsburgh’s South Side–a community struggling with poverty and filled with vacant lots–it can be hard to attract new residents. A development in planning now will try something new to achieve that: a housing complex will come with its own 23-acre urban farm.

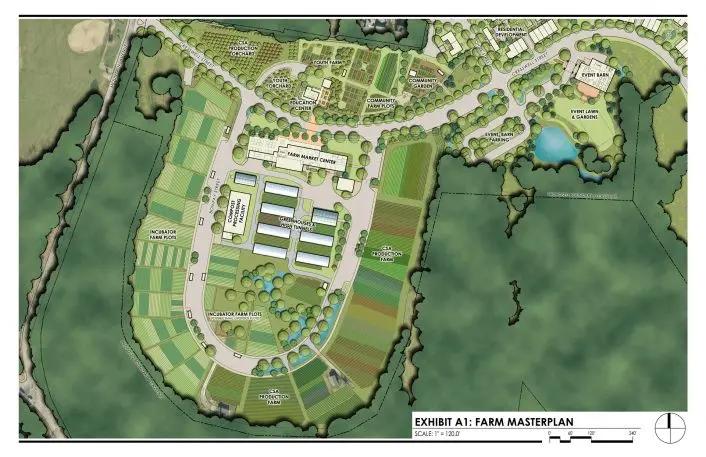

Built on the site of a housing project that was demolished in 2009, the mixed income development Hilltop Farm will include an orchard, incubator farm plots for aspiring farmers, community gardens and shared plots, a youth farm, greenhouses, a farmers’ market, and fields devoted to growing produce to deliver to people living in the townhomes on the property and to others in the city.

“When you work in distressed markets that need some driver for new residents, one thing that we’ve seen is a real desire to live near well-managed green space assets,” says Aaron Sukenik, executive director of the Hilltop Alliance, a local nonprofit community advocacy group that is coordinating the plan for the farm. “That can manifest as a greenway, or public park, or a trail network, but what really hasn’t been borne out locally . . . is an urban agriculture hub.”

“In a way, this will also be a defining asset for the neighborhoods that surround this place,” Sukenik says. In time, as more people move there, other vacant lots could also be redeveloped.

The project is also designed to immediately benefit neighbors who already live nearby. Right now, much of the area could be considered a food desert, with little access to fresh produce. Nearly half of households live on less than $10,000 a year, and many lack cars. When the farm is complete, some neighbors will be able to grow food themselves, or sign up for a CSA (community-supported agriculture) subscription that delivers produce as it’s harvested. Because the area has a refugee population that is used to farming communally, some of the community plots are larger than they would be in a typical community garden. An on-site farm stand will take SNAP benefits as it sells seasonal produce.

“This is a way of having increased access to affordable and culturally appropriate food,” says Jake Seltman, executive director of Grow Pittsburgh, an urban farming organization that helped study the feasibility of the farm for Hilltop Alliance along with Penn State Extension, and which helped lead community planning for the project. “We talk about food poverty, and space where people can grow their own food and know where it comes from, regardless of whether there’s a grocery store nearby, has a huge value.”

A youth farm and orchard, along with an education center, will help introduce students from nearby schools to farming. In the farm incubator space, aspiring farmers who may not have access to land–or who want to learn more about how to run a business–can come to the farm to use a plot of land and access other resources.

“Many of the [aspiring farmers] that we connect with live in the city and don’t want to drive–they want to live in the city and also want to grow food in the city,” says Seltman. “In Pittsburgh, that’s a challenge, because the land, if there is any land, is quite expensive, and further out, where it might be more affordable, the commute is a challenge. So an incubator farm where these folks can try it out in a space that’s closer to where they live is great.”

By farming the land–and leaving some hilly parts of the property covered in trees–rather than developing all of it for housing, the project also has other benefits. The land will be able to absorb stormwater in heavy rains, helping prevent flooding. The tree cover will absorb pollution. People can walk to buy produce rather than driving. The green space is also expected to increase property values; a 2012 study in the county found that smaller community gardens contributed to 5% annual increases in the value of adjacent properties. The farm is also designed to build community.

“When people from the housing are able to go to the community garden and farm together, and there’s a farm stand, there are authentic opportunities for people to connect around food and celebrate that connection to the land and each other,” Seltman says.

Though the team began studying the feasibility of the project in 2013, the fact that multiple parties are involved has made planning complex. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development owns the site, and the Pittsburgh Housing Authority manages it, though it plans to sell it to the city’s Urban Redevelopment Authority. The Redevelopment Authority will likely subdivide the property into “conservation” land, including the farm, and sell that to a land trust that will lease it for a nominal fee to Hilltop Alliance. The rest of the land will become the new housing. The Housing Authority is still going through a long list of steps required before it can dispose of the property.

In the meantime, Hilltop Alliance has access to the land and has planted its first cover crops–a process to prepare the soil for the future farm. While the housing will take longer to build, it could start growing produce for the neighborhood as early as next summer.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.