For a refugee trapped in an overcrowded camp on an island in Greece, it often isn’t clear how to prepare for an asylum interview–a step in the process of getting official refugee status in the EU–and for those who have started to lose faith in the system, it’s also sometimes hard to believe that an interview can change their fate.

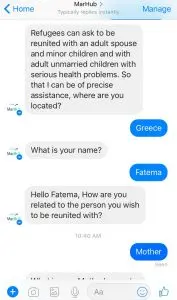

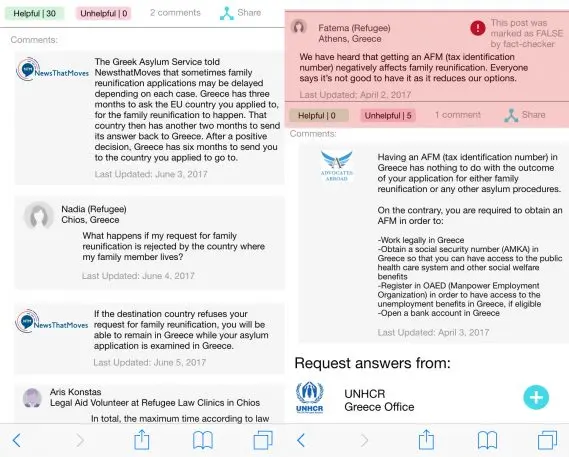

A new chatbot called MarHub (the name is a play on the Arabic greeting marhaba) is designed to help. After an asylum-seeker answers a few questions, the tool walks them through what to expect and how to present their case. Over time, the tool will expand to become a hub of information relevant to refugees, using the crowd to help vet the reliability of that information and flag details that seem outdated or inaccurate.

Since the refugee crisis in Europe reached its peak in 2015, many apps and websites designed to help smooth the refugee process followed, such as Migration Aid, which was designed to help people traveling through Hungary, or Refugermany, which helps new arrivals in Berlin open a bank account or learn German, or Refugee.info, which attempts to provide comprehensive information. But even though most refugees have smartphones–and desperately need information–many of the new tech tools are underused. Sites and apps often provide information that is too general or out of date, as understaffed organizations struggle to respond to day-to-day crises and make providing information a lower priority.

If part of the asylum application process changes, for example, a humanitarian organization might not be immediately able to update its own website to reflect that. The UC law professor, Katerina Linos, found that rumors in a refugee camp tend to spike with a major change in policy or procedure.

“Misinformation is kind of being fueled by these changes,” says Nomanbhoy. “Asylum seekers are so desperate to get an answer that these rumors spread, and people start to build on them, and that’s when there’s often violence in the camps and conflict. People are dealing with a lot of stress in those situations.”

They also often get information from unreliable sources. “When you talk to asylum seekers, what they’ll say is it’s so easy to get on the phone with a smuggler,” she says. “They always answer the phone, and they always have an answer. Whether it’s the right answer or not is a completely different question.”

For most people, the process begins with an admissibility interview asking why someone left Turkey, the waypoint on many journeys, to determine whether it would be safe to send them back. A second interview asks why someone left their home country.

“A lot of people mix up these interviews,” says Nomanbhoy. “They prepare for the wrong one. They’re not sure why they’re being asked questions about Turkey, and they don’t really know their rights going into the interview.”

In many cases, refugees don’t know that they can ask for a different translator if they need one, or that they can review the transcript of an interview to make sure it’s correct. One man the students interviewed was from Balochistan, part of Pakistan; he couldn’t get a translator for his interview who spoke Balochi, and struggled to speak English, not realizing he had a right to a translator. Some applicants might omit important details–one man went through the entire process without mentioning that one of the reasons he fled was because of his sexual orientation. Others, particularly Syrian refugees, may assume that the reason they fled is obvious, and not realize that they’re required to make a case for why they personally felt threatened.

The chatbot–which will be offered first on Facebook, and later on WhatsApp and via text, recognizing that refugees with limited wireless data are reluctant to download new apps–talks refugees through these details, provides sample questions for practice, and an Arabic mnemonic to help them remember key points such as making sure their story is consistent, and sharing emotion. At the end of the process, it gives someone the option to connect with a legal volunteer (lawyers are only provided in the asylum process after someone’s application has been denied and they are appealing).

Over time, the bot will use AI to learn to respond to many more questions. It will also be available in more languages–it is currently only available in English and Arabic, targeting Syrian refugees. But even in its early form, it can help give refugees some clarity on the confusing and stressful process of interviews. “In many cases, a lot of people described it as kind of like an interrogation,” says Nomanbhoy. “After going through so much trauma and having to relive that trauma and talk about things that are super emotional, and then have someone interrupt you halfway through your story and ask very detailed questions can be quite frazzling for people. So knowing what to expect going into that can really help.”

While some organizations are unwilling to give refugees details about how long the process of applying for asylum can take–worrying that it might push people to take risks with smugglers–MarHub’s founders believe in full transparency so refugees can make the best-informed decisions. They plan to launch the first version of the chatbot in November, partnering with a trusted local organization called RefuComm, and after a core group of people begins to use it and give updates on their own experiences, the startup plans to use anonymized data to help give better estimates of wait times for someone from Afghanistan versus Syria or Libya.

“One of the challenges of being in a refugee camp is not knowing how long you’re going to be there, being so bored, and feeling like you’re wasting time,” she says. “So many people said this to us: ‘We’re just wasting our lives, we should move on, we have nothing to do and we don’t know how long this is going to take.’ I think that’s when people lose faith in the system.” Refugees told her that if they knew the process was likely to take six months, it would help–not knowing adds to a sense of loss of control.

That data is valuable for the organizations, who currently spend large sums of money trying to evaluate their impact; MarHub thinks that its system, if used by enough refugees, would be an efficient way to get that feedback. If NGOs or UN agencies pay for it, the service could be financially self-sustaining or even profitable. The students also see the opportunity to eventually add carefully-vetted advertising.

“When you think about, for example, 900,000 Syrian refugees in Germany, they are this completely new market,” says Nomanbhoy. “Many of them will have to buy things like diapers and they don’t have any brand association to many of the local brands. In many cases, this is a completely new audience for a brand.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.