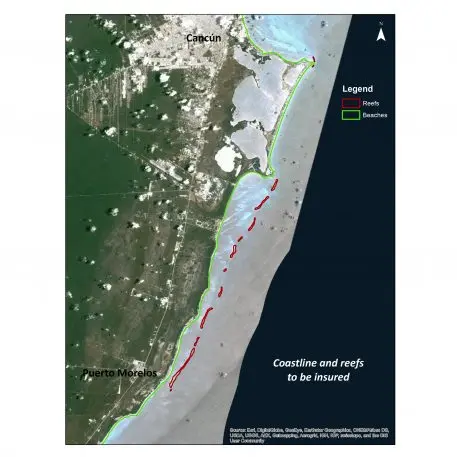

A 40-mile stretch of coral reef off the coast of Puerto Morelos, Mexico–part of the roughly 700-mile long Mesoamerican Reef, the second largest in the world–is both a draw for tourists and a natural barrier that helps protect the coast’s resorts from flooding and damage in hurricanes. But like other reefs, it’s facing multiple threats, including warming water, pollution, and damage from storms that are becoming stronger because of climate change. This has convinced local businesses to pay for something that is the first of its kind: an insurance policy for nature.

In September, beachfront hotels and other businesses in the area will start contributing to the new Reef & Beach Resilience and Insurance Fund, which pays premiums to the insurance company Swiss Re AG. In the event of a major storm that could damage the coral, Swiss Re will quickly offer payouts that can be used to restore the reef so it can continue to attract tourists and protect coastal property in future storms.

“You have this natural asset that’s part of the natural landscape, but it’s providing all this risk reduction to the tens of billions of dollars’ worth of economic assets that sit behind it,” Kaplan says. “No one actually ever thought about it that way before . . . if it were not there, the potential loss scenarios would be quite high, or much higher than they are in reality today. Then you can put a price tag on that exposure, on that reef.”

The insurance company formed its Global Partnerships team six years ago to begin to address the fact that only a fraction of the damage from natural disasters–around 30%–is covered by insurance. In 2005, when 1,800 people lost their lives in Hurricane Katrina, the insurance industry paid the largest total it had paid in history; the year before, when 200,000 died in an earthquake and tsunami in Sumatra, “it was almost a nonevent for the insurance industry,” Kaplan says.

“We viewed that as a catastrophic failure of the insurance industry’s intent to do its job and add its value,” he says. “So our team stood up for the purpose of closing what we refer to as the protection gap: the gap between the portion that’s covered by insurance and the actual economic impact of different types of disasters and liabilities that governments face.”

For governments, economic costs in the wake of disasters can total hundreds of billions of dollars a year around the world–that’s both a societal problem and a business opportunity for insurance companies. “Closing this protection gap is critical to protecting our economic future, but also creates a new market for the industry,” he says. “This is particularly true if you now consider nature as an insurable asset.”

Damage to a coral reef during a hurricane would typically be borne by society. After Hurricane Wilma caused $7.5 billion dollars of damage in Mexico in 2005, hotels along the coast began paying the government extra taxes that were meant to be used to protect the beach. Now, those same funds will contribute to insurance premiums instead. The payouts will go to both beach cleanup and reef restoration.

The insurance policy is parametric, meaning that it’s triggered by a particular event–in this case, a severe storm–rather than by damages. That means that no adjuster needs to come out and assess the damage to the reef; instead, if a storm meets qualifying criteria, there’s an automatic payment. The policy is triggered strictly by storms, rather than by other threats that corals face such as rising ocean temperatures or pollution, though future policies could address other issues.

“In the attempt to create a market you have to start with the steps that people are most comfortable with and they are already familiar with,” says Kaplan. “Hurricanes are probably the most modeled natural hazard in the world, and therefore there’s the greatest amount of comfort around how they behave and what they cost. The idea is we start here in Mexico with the coral reef talking about hurricanes, but 5 or 10 years from now, I hope we’re talking about . . . a much broader array of natural hazards.”

A claim will be paid in 10 days or less. “You get immediate cash influx for the repair, and the reef needs immediate attention,” says Kathy Baughman McLeod, managing director of climate risk and investment at The Nature Conservancy. “The corals break off and you’ve got to pick them up, and rest them, and they have to be reattached. That can all happen, but they can’t be left to break off and float away, because they’ll die and you’ll lose the health of the reef.”

After a severe storm, “coral first responders” will assess the damage, and take broken coral to nearby coral nurseries for rehabilitation. If the reef loses some of its height–critical for protecting the coast–artificial structures can be used to build it back up (the coral soon grows over these structures).

If the reef is damaged in a storm that doesn’t meet the criteria of the insurance policy, the fund is also designed to be used as self-insurance, so it will still be possible to make repairs. The fund will also provide money for ongoing maintenance to care for the reef between catastrophic events. Both restoration and ongoing care will happen using methods outlined by The Nature Conservancy.

“We had to figure out how many people in how many boats you need for how many days, and how much does it cost,” says McLeod. “They’ve got to clean up the reef, pick up the corals, rest the corals, and assess the damage. Part of the plan is that we’ll have that preordained science and that it’s already agreed to, so you know exactly what to do in which order.”

After the pilot in Mexico, The Nature Conservancy hopes to create a replicable process that can be used in other communities that depend on coral reefs in similar ways. It also plans to work with partners to develop insurance policies for other ecosystems, such as mangrove forests, that also provide critical services to the people living nearby.

In many cases, nature outperforms artificial structures for protecting coasts, such as seawalls, from the increasingly severe storms that are coming with climate change. “We always talk about risk reduction, and if you invest a dollar today here, you see $4 here,” says Kaplan. “The reality is that the biggest bang for your buck is almost always in green infrastructure.”

In the future, insurance policies for nature may work in tandem with traditional insurance; just as some health insurance companies give discounts to people who regularly go to the gym, a company insuring coastal property might eventually give a discount to a building owner who is helping protect a nearby reef.

It’s long been known that coral reefs have benefits beyond their beauty. But if nonprofits and others attempting reef restoration have struggled to find funding in the past, quantifying those benefits and insuring them could be a novel way to help change that.

“These natural systems are superheroes of climate adaptation and protecting these economies,” says McLeod. “The idea that nature is so valuable we put an insurance policy on it is basic. But it can change the way we look at nature and sustain economies along the coastline forever.”

Correction: We’ve updated the headline of this story to reflect that the insurance has not yet gone into effect.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.