The Balbina hydroelectric dam in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest is, according to more than one expert, the worst hydro plant in the world. With too little water to run its five giant turbines, it operates at a fifth of its 250-megawatt (MW) capacity. The environmental and human costs required to build it were enormous and horrendous: In the 1980s, engineers flooded 900 square miles of rainforest, obliterating land occupied by indigenous tribes. And because of decomposing plant matter in the lake, Balbina may emit enough methane–an especially dangerous greenhouse gas–that its climate profile is no better than a coal plant, some scientists say.

“Balbina is among the projects that are known in Brazil as pharaonic works,” writes ecologist Philip Fearnside. “Like the pyramids of ancient Egypt, these massive public works demand the effort of an entire society to complete but bring virtually no economic returns.”

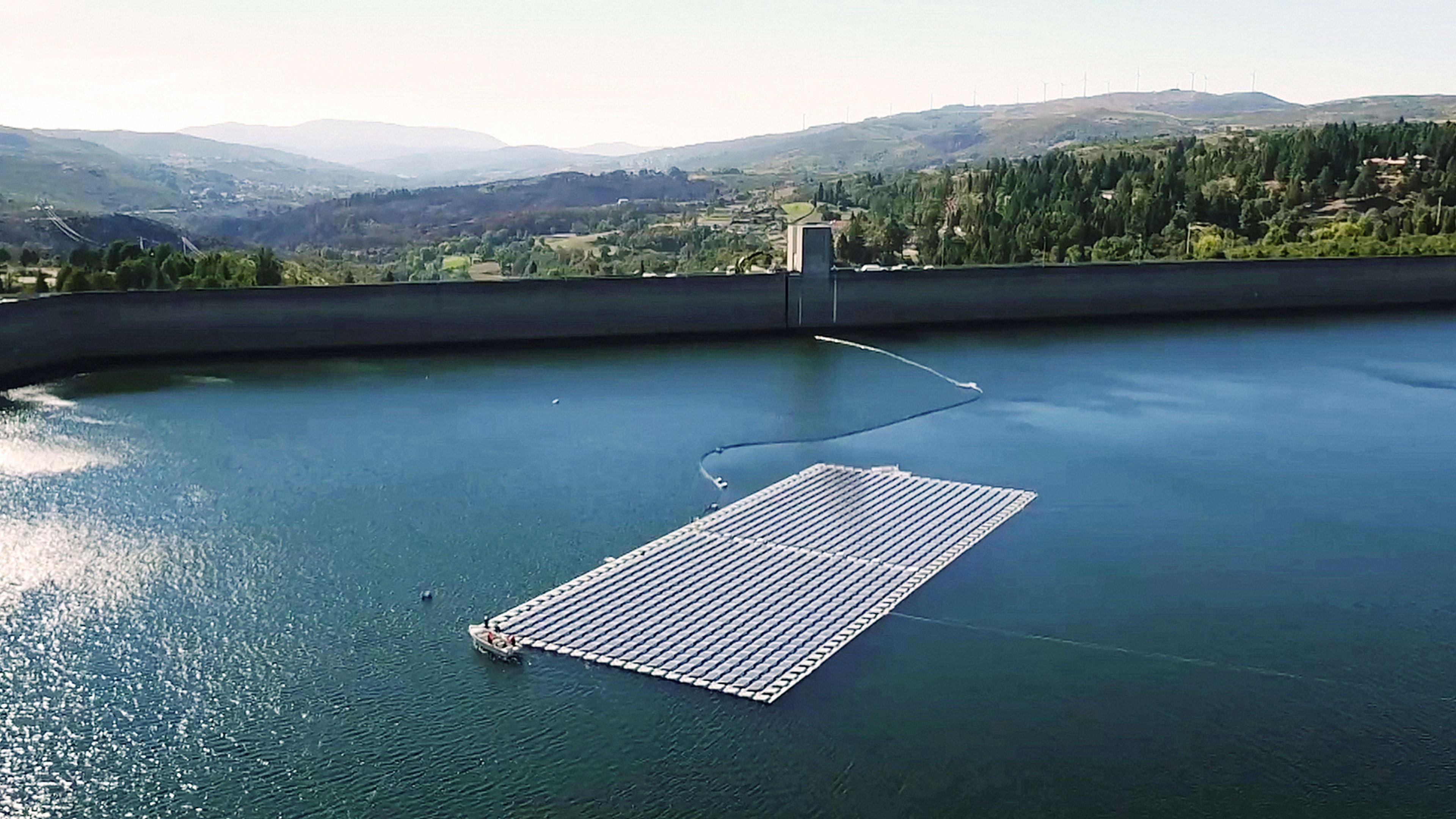

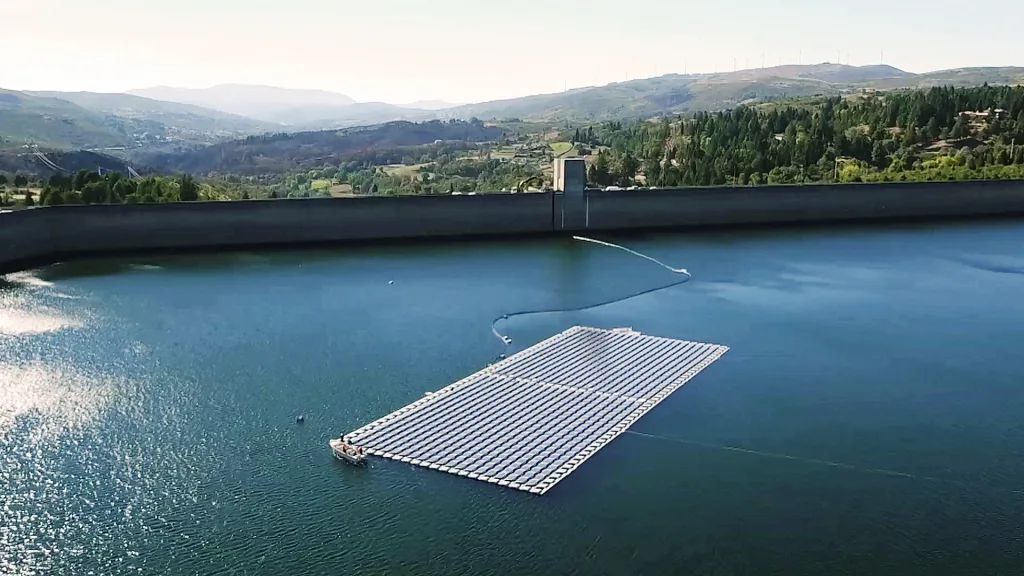

The French company behind the project in Brazil, Ciel & Terre, also recently completed a similar installation in Portugal, at the Alto Rabagão dam, and it’s working on deals in North America and South Asia. It argues that putting panels into the waters above a dam enhances a site’s output, and makes use of spare storage and transmission capacity built in hydro projects, pharaonic or otherwise. Moreover, the panels offer power at peak times of day, and help to reduce evaporation and settle the water.

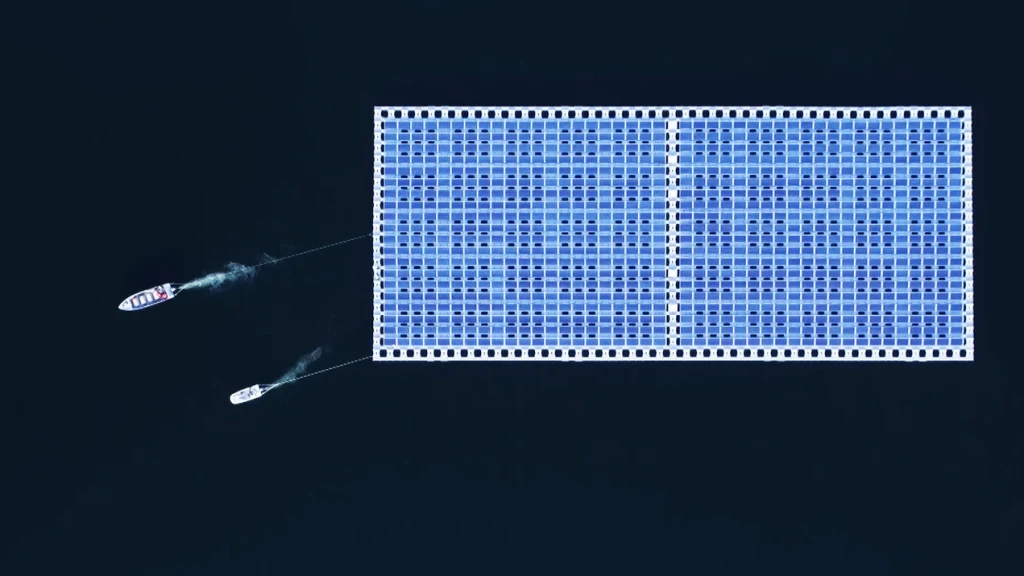

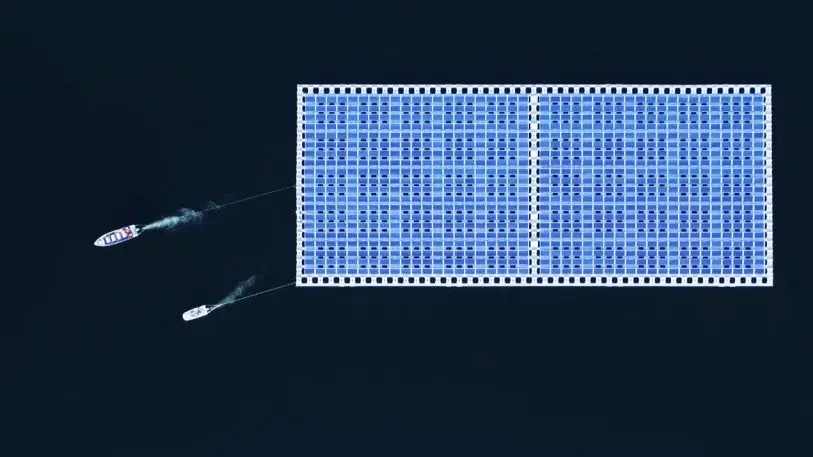

“When dams aren’t running at full capacity, you have a huge opportunity to use that existing infrastructure,” says Eva Pauly-Bowles, international sales director at C&T. “This is scalable as much as we want it, as much as the electrical infrastructure can take it.”

The arrays are moored with bottom and bank anchors using high-tension cable lines. C&T monitors for water and wind conditions, ensuring they stay more or less in the same horizontal position. However, the arrays can move up to 100 feet on the vertical, as the water level behind the wall rises and falls.

Pauly-Bowles says non-recreation sites are best for the projects, as having human beings around tends to complicate permitting and operations. She, therefore, doesn’t expect C&T’s arrays atop the Hoover Dam anytime soon. But Lake Michigan is another possibility. Its pumped storage stations–which store hydro-energy (potential electricity) for use during peak times–are other possibilities.

“Working on top of a hydro-dam, there’s the synergy of having the electrical infrastructure already there. Most of hydro dams have been over engineered so they have space for solar,” Pauly-Bowles says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.