In his 2011 book Reinventing Fire, the renowned physicist and environmentalist Amory Lovins laid out how the U.S. could power itself largely with renewables by 2050–and save money at the same time. By tripling investment in energy efficiency and quintupling the use of solar, wind, and other clean energy sources, he says we can cut carbon emissions by 84% while growing the economy 2.6 times over. What’s more, he argues, we could make the transition without any major new inventions and without any acts of Congress.

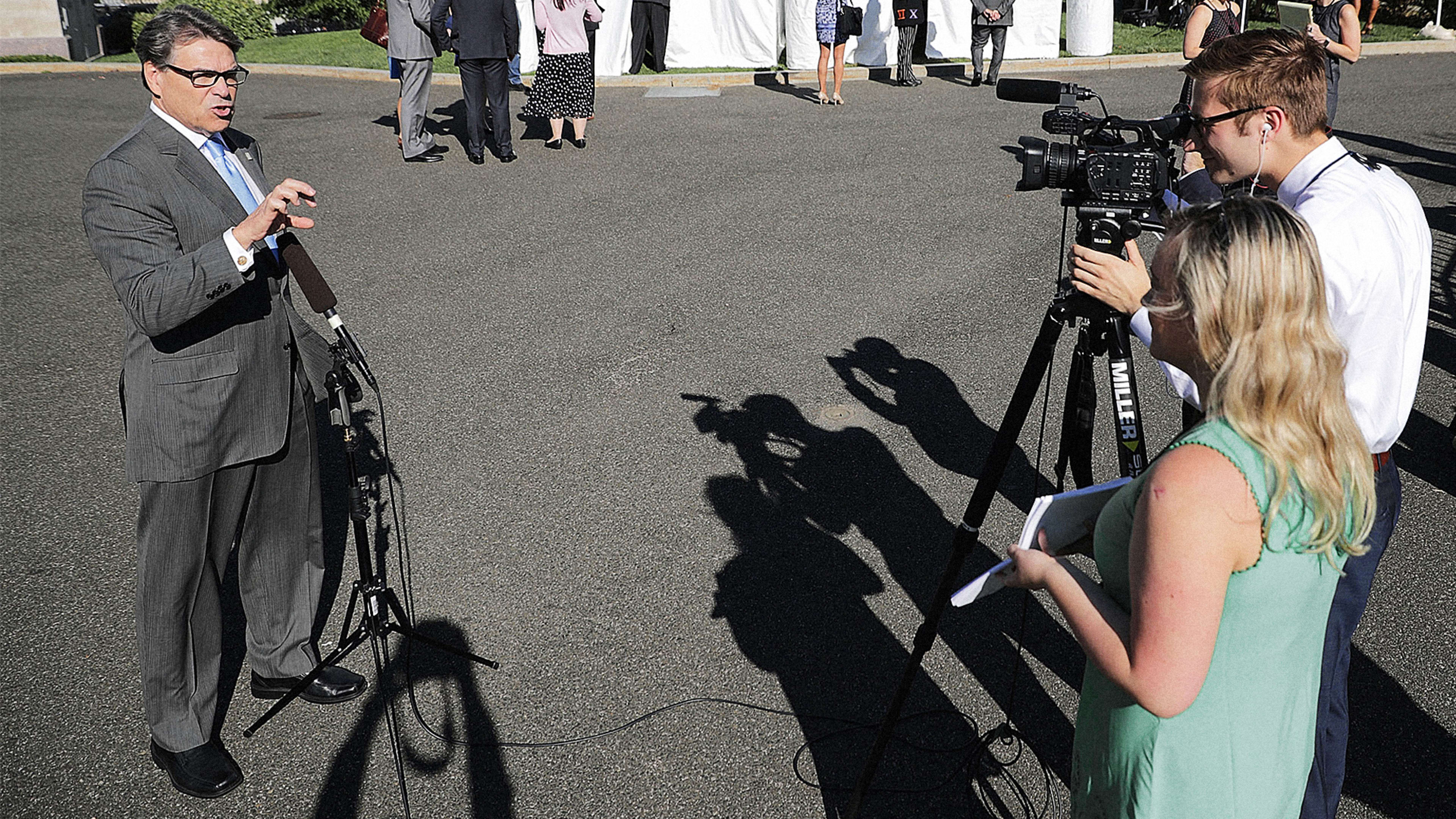

Six years later, after a period of federal and state-level government support for renewable power and heavy private investment, Lovins, chief scientist at the Rocky Mountain Institute, says the U.S. is still on a path to meet those targets. But he’s concerned this progress could be undermined by the Trump Administration. Specifically, he worries about statements by Energy Secretary Rick Perry, who says regulations have privileged renewables at the expense of nuclear and coal-fired power plants.

As Texas governor, Perry was an ardent states’ rights advocate, resisting any interference from Washington as an affront to the 10th Amendment. But, as Energy Secretary, he’s floated whether his department could intervene in state power markets on national security grounds, solidifying the position of coal and nuclear power across the country. “Are there issues that are so important to the national security of this country that the federal government can intervene on the regulatory side? I’ll suggest there are,” he told the Bloomberg New Energy Finance Summit in April. Around the same time, he ordered an internal Department of Energy study questioning whether government support for renewables is threatening grid reliability and harming coal and nuclear.

To write the report, Perry put in charge his chief of staff, Brian McCormack, previously vice president of political and external affairs at the Edison Electric Institute, a trade group representing investor-owned utilities, and Travis Fisher, formerly of the Institute for Energy Research, a “free market” think-tank funded by the Koch brothers, which regularly assails renewable energy.

Still, Lovins feels the need to challenge Perry’s rhetoric because it superficially makes sense, and there’s a good chance that people, given the inclination, might be willing to believe it. Lovins’s vision of a remorseless shift to renewables and efficiency is prefaced in market economics and undermined by Perry’s wrench in the otherwise ineluctable process. If he’s prepared to prop up up coal and nuclear, Perry makes reinventing fire a slower process.

Perry describes baseload power—coal and nuclear power stations—as “fuel on hand.” It’s available when you need it, as opposed to, say, power from a distant solar farm, which is subject to weather and dusty conditions. But this argument misses the ways coal and nuclear can also be unreliable, Lovins says. Coal piles freeze up in cold weather (in 2011, 50 fossil-fuel plants in Texas shut down because of frozen piles, burst pipes, and other issues, he says). Trains carrying coal to those plants derail or catch on fire. Nuclear plants need regular maintenance and repair. Half the current national nuclear fleet has closed down for repair at least one year, and 10 of them have closed for more than a year twice. Japan, meanwhile, lost its entire nuclear capacity in the wake of the Fukushima disaster–almost 30% of its electricity supply at the time.

In other words, the idea that renewables are flakey luxuries while coal, gas, and nuclear are steadfast is, at this point, not supported by the evidence, Lovins says. In fact, almost the opposite could be true: Renewables may not offer constancy, but they’re not unpredictable.

“With renewables, output varies with the weather and the rotation of the Earth, but those are not unexpected or unpredictable forced outages,” Lovins says. They are no more unpredictable than the demand for electricity, which is constantly shifting for myriad factors. Solar systems have a failure rate of just 0.2%; they’re generally easily fixable; and the power they produce is “dispatchable.” That is, grid operators can send out for power from a wind or solar farm in an instant, while a power plant will take hours and days to fire up, and often at a large cost.

In fact, a recently leaked version of the Perry-commissioned study backed up Lovins’s points. It says “most baseload power plant retirements have been the victims of overcapacity and relatively high operating costs [and] often reflect the advanced age of the retiring plants” and fails to blame government policy as the main cause of coal and nuclear’s decline. However, the report was likely written (and leaked) by permanent staffers at the DOE rather than Perry’s political appointees. The final version may well be more favorable to Perry’s point of view.

If he does want to intervene in state power regulations, Perry could turn to an Obama-era law that allows the DOE to keep existing power stations open in emergency circumstances. But Lovins thinks this could only ever be a stopgap measure and it’s sure to roil the vast majority of people who’d rather the best and cheapest energy won in the end.

“The exit of these coal and nuclear plants is economically efficient and logical. The secretary would like to change that by putting his thumb on the scale, but he’s unlikely to succeed,” Lovins says. “If he did, he would hobble competitive power markets and suppress innovation that we baldy need, and he would encourage corrupt and rent-seeking behaviors and actually harm national security, not enhance it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.