Secrecy is like a religion at Apple. It’s baked deeply into the DNA and culture of the company. So, when the Outline got its hands on a (leaked) recording of a product secrecy training session for Apple employees, it published the juicy details in a story today.

The training session was given by an Apple group called the New Product Security team–made up of former National Security Agency (NSA), FBI, Secret Service, and military people–that investigates leaks about upcoming Apple products around the globe. The group was formed after an Apple employee famously left an iPhone 4 prototype in a bar in 2012—the device was recovered and subsequently described in detail by Gizmodo.

The training session featured videos in which Apple employees can be heard talking about the need for secrecy. “When I see a leak in the press, for me, it’s gut wrenching,” one employee says. “It really makes me sick to my stomach.”

As a tech reporter I’ve witnessed Apple’s wall of secrecy firsthand many times. Sources with ties to the company often suddenly register a look of disquiet when asked about Apple, then nervously close down the conversation. Nobody wants to risk disfavor, and possible abandonment, by the world’s biggest tech company.

I have several friends who work for Apple, and we never talk about the company. If, for some reason, the conversation moves around to something related to Apple, I can feel the wall go up–time to talk about something else.

The Outline‘s story reveals that Apple has gone further with its secrecy efforts than most of us even imagined. Has Apple established a “culture of fear” among employees, suppliers, and contractors? I’ve heard different answers to this question from people in each of these communities.

Secrecy is arguably more important to Apple than to other companies because of the way Apple prices and sells its products. It’s true that Apple products are thoughtfully and meticulously designed, and its famously tight hardware and software integration pays big dividends in the final user experience. But Apple, in the cold calculus of features and specs, gets far more money for its products–and far higher profit margins–than its competitors.

How? Apple is in large part a product marketing company. The market value of the products is dictated by the way consumers can be made to feel about them. It’s often been said that Apple products are “aspirational,” that they have a way of conferring status on the owner. I believe that consumers truly do feel this way about Apple products in a way that they don’t do about, for example, Samsung products.

It takes a lot of marketing genius to build, cultivate, and maintain this reality. Secrecy and tight control of the narrative around new products are vital ingredients.

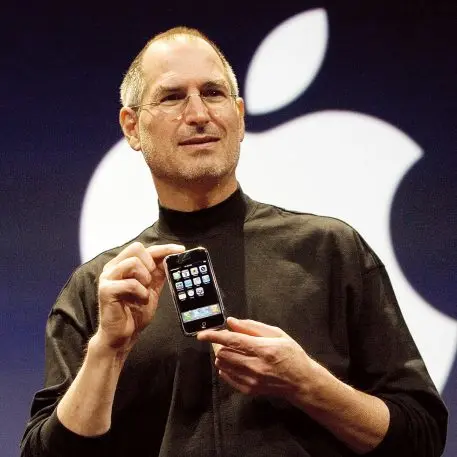

This approach worked during the Jobs era and, I’d argue, it still works, albeit in a slightly different way, in the Tim Cook era. Today’s Apple lives at the heart of a never-ending media windstorm, the subject of constant attention from 24-7 Apple blogs, general tech media, mainstream media, and Wall Street. It’s also a far richer and more powerful company now than in the days of Jobs.

These days, leaks play a big role in the buildup to a new product announcement, I’d argue. The full hype cycle around new Apple products—starting with the very first rumors and leaks—is a steadily building drama that leads up to the pleasurable suspense before the launch, the delight of the reveal, and (hopefully) the consumer’s decision to buy it in the days and weeks following the event. The leaks are like little splashes of gasoline that keep the fire building throughout.

Tim Cook said in 2012 that he intended to “double down” on product secrecy, but in general (there are some recent exceptions), Apple has had a harder time than it once did keeping news bottled up. In recent years, Apple events have had fewer and fewer surprises, even after Tim Cook talked about doubling down on secrecy. There was a time when, as a rule, almost nothing leaked.

While leaks can help build interest in upcoming products, they can also directly hurt the sales of those devices that are already on the market. Case in point is the upcoming iPhone 8, which will likely be unveiled next fall. Apple, of course, wants consumers to keep buying the iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus that are available today, and not hold out until late this year to buy the iPhone 8. In fact, Cook said during Apple’s last earnings call with analysts that stories like this one have led to softer-than-expected sales of existing iPhones.

In the end, Apple’s obsession with secrecy and drastic steps to stop leaks may only perpetuate the problem by placing a higher value on the leaks. For people like me, details on unannounced Apple products or services are considered “big game.” Regularly breaking such stories can be a career-making habit for some tech journalists. Readers, it turns out, like to read about things Apple really, really doesn’t want us to know about. How truly useful this kind of journalism is remains a question for another day.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.