Behind two opaque white glass doors on a storefront on Manhattan’s 14th Street, a team of sous chefs is chopping, marinating, and frying food for the Flatiron lunch crowd. A young intern wearing a loose T-shirt and a red baseball cap sits among a collection of stainless steel appliances, a warming cabinet, preparation counters, walk-in coolers, and industrial-size sinks. He’s staring intently at a laptop. “He’s measuring the degradation of temperature over time for food items,” says J.J. Basil, the lead chef at David Chang’s new outfit, Ando, a ghost of a restaurant that has no physical dine-in location.

Chang is a serial restaurateur who has made his name on innovative comfort cuisine through the umbrella of Momofuku. In 2004, he launched his first spot, Momofuku Noodle Bar, and has since amassed a series of restaurants in New York City, Toronto, Las Vegas, and Washington, D.C. Now, with Ando, hungry customers can’t just come and sit down—or even order pickup. All the food is made to be delivered for $9-$12 in 30 minutes or less.

Related: David Chang Wants To Fuku You Up

Other startups have attempted low-overhead kitchens with a focus on delivery, but so far, there have been no breakout successes. Chang thinks he can make his concept thrive by doing what’s he’s always done: run restaurants. In his mind, Ando will succeed if he’s conservative in the number of kitchen hands he hires, arms his staff with efficient equipment, focuses on profitability off the bat, and constantly iterates recipes until something sticks. He’s hired top talent to pull it off, like chef Basil, a former sous chef at WD-50, and most recently, Andy Taylor, who was previously CEO of Hale and Hearty Soups.

Ando came into being in May 2016, and until recently, only serviced Manhattan’s Midtown East neighborhood. It’s since expanded to Flatiron. As Ando was growing, Maple, a similar food-delivery service (one that Chang invested in), was shutting down. And Maple is not the only fledgling delivery startup to fall. Sprig and SpoonRocket, two West Coast companies that have also gone kaput, were unable to solve the costly inefficiencies of building new technology, anticipating demand, and managing labor. Another company, Munchery, has struggled with high levels of food waste. Chang thinks the key to mastering food delivery without a storefront to lure in passersby is making delicious meals that people love. “If we can just make good food and get it to them fast, I think that’s the name of the game,” he says.

The Domino’s Effect

I meet Taylor at Ando’s offices near Union Square. The sparse office, which previously belonged to a real estate group, has a windowed partition in the front. Behind the wall, there are conference rooms, a small kitchen where two men tap away on keyboards, and an open space where a team of people sit at long tables, looking at large monitors.

Taylor sees delivery from nimble kitchens as the next wave in the technology-enabled conveniences that have become embedded in the lives of urban dwellers. Referencing the popularity of ride-hail services, he says, “If you’da said five years ago I was gonna stand on a corner, press a button, and then get into a stranger’s car to go to dinner, I would have said you were crazy.” In his lilting British accent, he continues, “But now it’s part of the culture, isn’t it?”

Taylor is known for growing chain brands. He was chief operating officer at Pret A Manger and expanded the brand in the U.S. from 11 stores to 33 in New York, and launched the brand in Washington, D.C., Boston, and Chicago. When he became CEO at Hale and Hearty, he was charged with revitalizing the company and building its reputation for homemade soups. The challenge he foresees at Ando is finding a core audience.

Related: An Exclusive Look At Ando, David Chang’s Top-Secret New Delivery Restaurant

“If you’ve got a big fat corner on Lexington Avenue, a lot of pair of eyes see it every day, and people just know who x-brand is,” Taylor says. “It becomes more familiar. We don’t have that luxury.”

His arrival at Ando makes a lot of sense, considering Chang’s inspiration for the new project isn’t any newfangled foodie service like Munchery, but rather, Domino’s. That’s not to say that he wants to make mediocre food mass-prepared to satisfy hungry sports fans or drunken college students. He’s looking at the way the pizza company is using technology—namely apps—to handle a high volume of orders. In February, Domino’s mobile sales made up 60% of its overall sales. The company is dominating fast food.

Tech To Support The Food

Even though on-demand lunch and dinner services are, at their core, food services, many have been the brainchildren of engineers and businessmen—”tech people,” as Chang calls them. These are people who don’t have experience in hospitality and team up with chefs to design a menu, but don’t necessarily value their ability to run a restaurant.

Chang has met a lot of individuals like this as he’s looked for partners for Ando. “One guy was like, ‘I can replicate your intuition. We don’t really even need you,'” he says. A lot of these food-service-without-foot-traffic startups have focused on the technology. Some engineers believe all they need to do food well are mobile apps that make ordering a meal as magically simple as hailing an Uber or Lyft.

But Chang thinks they have the equation wrong: It’s the tech that should support the food. And to gain a following, the food has to be good. So he’s building Ando like he would any restaurant: around a concept. But lunch, it turns out, is hard. These days, people are more concerned with healthy eating than they were 10 year ago. They’re also eating out less. And yet, according to research from the NPD group, delivery appears to be steadily on the rise, as more people work from home. This is especially true for food that’s not pizza. For these reasons, Chang and Basil are diligently researching and testing new dishes, trying to nail down the recipes that customers order again and again.

A little over a year after launch, Ando has yet to win over the masses. A less than savory review from Eater last year basically told Chang to do better on making meals for delivery. “I realize that some people think our food is bad,” he says.

But none of his other restaurants were successful immediately, and he doesn’t expect Ando to be any different. What’s important, he says, is that the staff stay lean (so to speak) while he and his team perfect the menu. Using another culinary metaphor to explain the importance of hiring only the number of people absolutely necessary, he says, “I always view everything through the whole analogy of salt to taste because you can never take salt out of the dish. You can always add.”

“A restaurant is about being profitable as soon as possible,” Chang adds. That same wisdom is not always true for tech startups. While some have bootstrapped themselves into world domination, those in the delivery space have received ample funding that’s allowed them to spend a lot of money to scale. Chang has always created his restaurants on a budget and thinks this approach has set up his various ventures for longevity. “It has to work,” he says. Why? Because his and his staff’s livelihoods depend on it.

The Art & Science Of Delivery

When he’s crafting a menu, Chang wants to appeal to a wide customer base, much like he does with the haute comfort food he serves at his many restaurants. He sees this more mainstream audience as his next big trial. This group can be just as difficult to please as foodies. “If you take a step back, you’ll realize that ‘challenging’ and ‘difficult’ is no longer on the margins of couture dining, but right down the middle,” he says.

Ando also comes with unique challenges that wouldn’t be issues in a sit-down eatery.

For one, Basil says he’s limited in the kinds of dishes he can make. At a quick-service restaurant, like Fuku, a cool bread-and-butter pickle can be paired with fried chicken inside of a buttery bun for contrast. But when that same meal is bundled up for delivery, the flavors meld together. “It’s the most challenging thing I’ve done so far,” says Basil, who during his time at WD-50, mastered such culinary marvels as an aerated foie gras terrine.

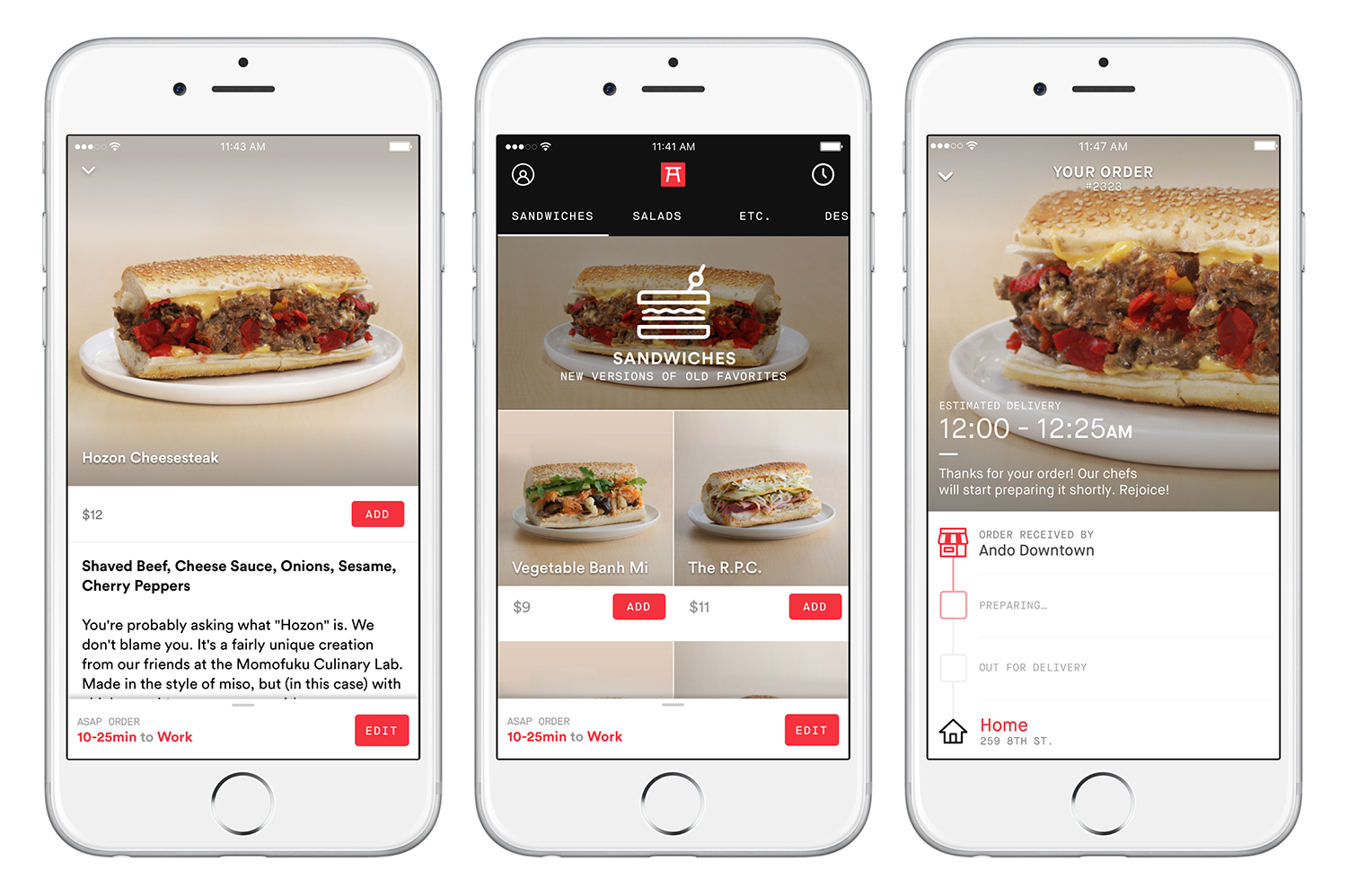

Right now, Ando is trying to make its name on sandwiches, salads, or bowls—healthy mixes of grains, veggies, and meats. Its current standout is a rich cheesesteak made with miso and chickpea paste that hardly resembles its Philadelphia originator and could put you to sleep if eaten in the middle of the day. Ando also has a green bowl with chicken and guacamole that is acidic in a way that foodies might appreciate. But neither of these are the knockout lunch hit Chang knows he needs.

“We’ve always taken this approach of trying to make mistakes and trying to make the right kind of mistakes,” Chang says. “You have to make it and then test it out and then tweak and constantly make iterations. That’s how we do it. I know it’s sloppy and inefficient, but I don’t think there’s any other way for us to figure it out.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.