Figure 1 has made a name for itself as a social network that lets medical professionals discuss photos of patient conditions with colleagues around the world.

“They can learn in real time from other people experiencing and seeing cases,” says Dr. Joshua Landy, a practicing physician and cofounder of Figure 1. “If you’re seeing a case, you can take a picture of it, you can describe it and ask for help, and you can even page a specialist.”

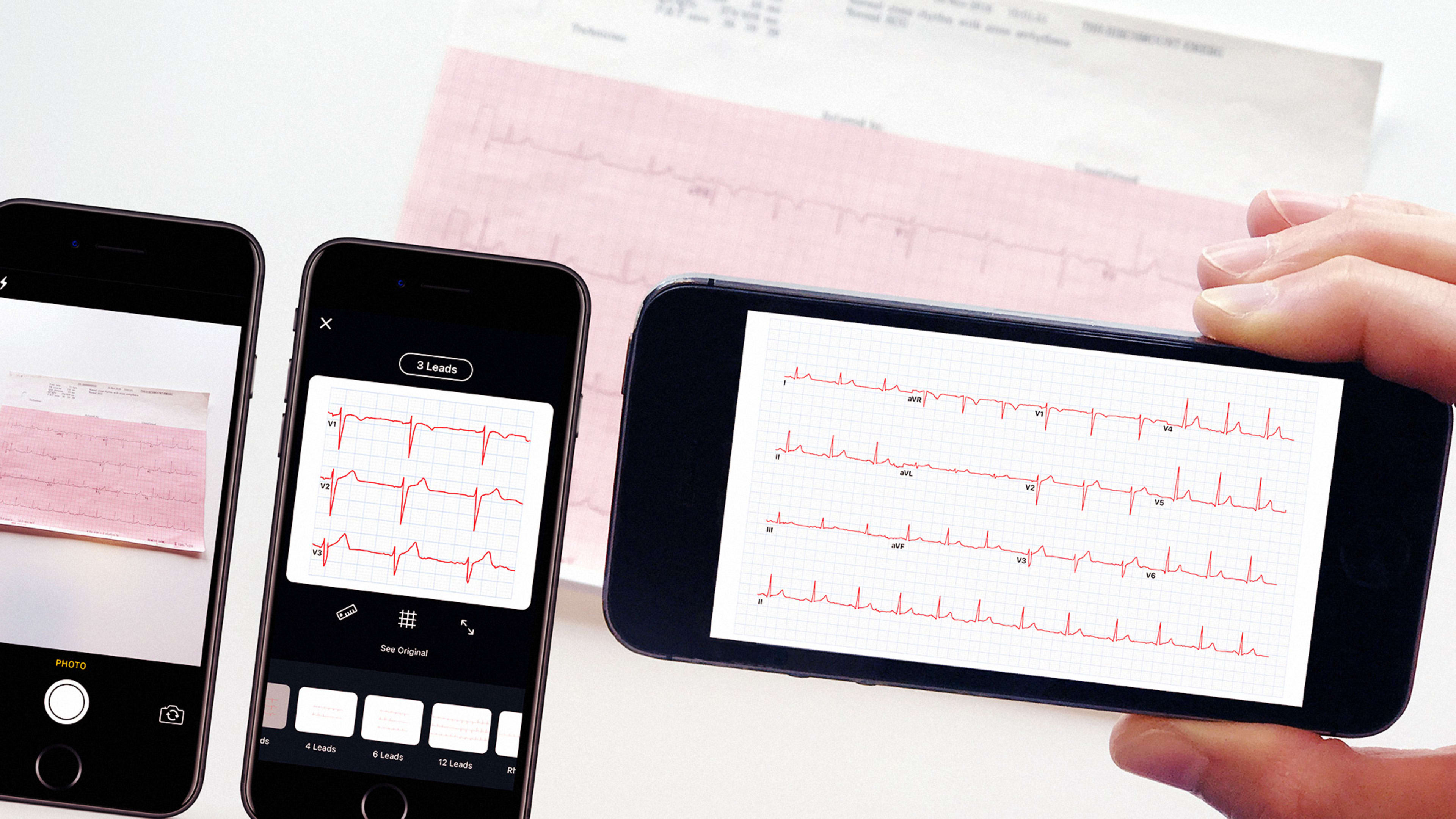

Now, the Toronto company sometimes referred to as the “Instagram for doctors” plans to introduce artificial intelligence into the mix, starting with a feature to turn photos of electrocardiograms into digital data. The company is planning to formally announce the feature later this month at the International Congress on Electrocardiology in Portland. At first, experts will be able to weigh in on the meaning of the measurements, but in the future more advanced machine learning systems may be able to provide their own insight into what particular readings mean.

Related: On “Instagrams For Doctors,” Gross-Out Photos With A Dose Of Privacy Concerns

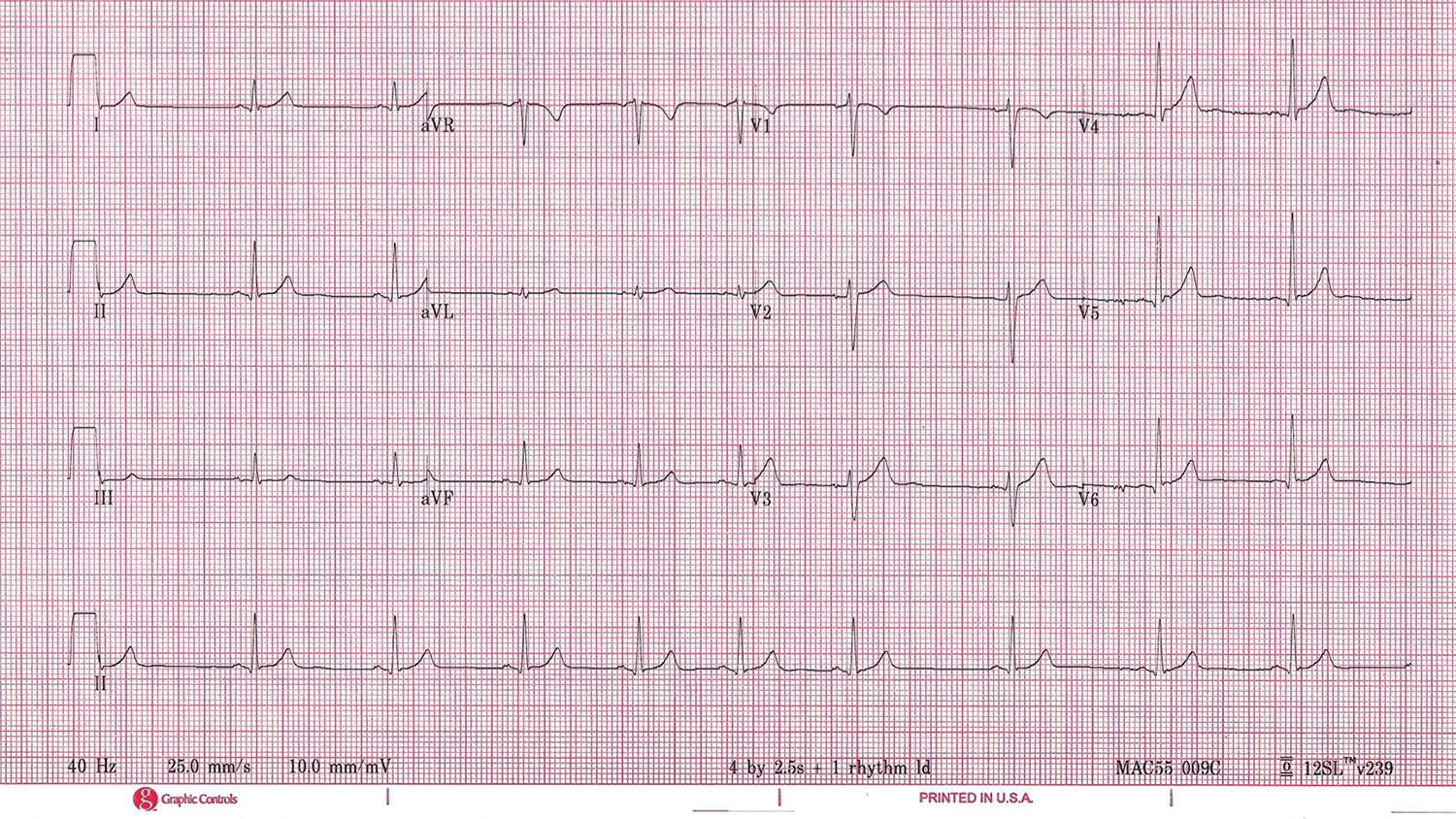

Electrocardiograms translate electrical impulses in the heart into line graphs that doctors can read to diagnose patients. While they’re naturally useful in checking for heart attacks and other cardiac issues, experts can sometimes also spot other conditions in ECG readings, from pneumonia to Parkinson’s disease, Landy explains. And the readings, often considered a vital sign on par with body temperature, blood pressure, and pulse rate, are standardized enough to be a natural target for digital processing.

“They are almost perfect fodder for computer vision and machine learning,” Landy says. “They’re self-similar, they’re stereotypic, they’re immediately recognizable by an algorithm.”

Experiments testing how machine learning can potentially be useful in health and medicine have been more common in recent years, but so far they haven’t had much impact on the average doctor’s practice, Landy says. That echoes what independent experts in the field have said as well.

“We examine applications of deep learning to a variety of biomedical problems–patient classification, fundamental biological processes, and treatment of patients–to predict whether deep learning will transform these tasks or if the biomedical sphere poses unique challenges,” a group of 27 researchers wrote in a paper released last month. “We find that deep learning has yet to revolutionize or definitively resolve any of these problems, but promising advances have been made on the prior state of the art.”

Related: This Doctor Is Using Telemedicine To Treat Syrian Refugees

Figure 1 hopes to change that with a tool that the more than 1 million doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals on the platform can immediately use to their advantage.

Even a first iteration of a machine-learning algorithm for detecting ECG images had about an 85% accuracy rate and the company, which is collaborating with Alexander Wong, Canada Research Chair in medical imaging systems at Ontario’s University of Waterloo, is working to further hone its approach. Figure 1’s library of medical images, including ECGs, provides an easy training set for code to detect ECGs and extract data. The company is partnering with a number of institutions to assemble a broader sample still.

“We’re only going to be using aggregated, anonymized data to collect a training set,” says Landy.

He says there may be future applications in other fields of medicine in the future, especially in other cases where lots of photos are “stereotypical and self-similar.” That could mean photos of dermatological conditions, or in common medical situations like caring for a wound, where doctors routinely observe the same feature on a patient.

A smart app could one day take a series of pictures of a wound, and confirm that it’s shrinking in size without the need for physical measurements, Landy says, though the company is likely to test to make sure any features it introduces are actually useful to its users.

“The most important thing in building software is making sure you’re actually building something people want to use,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.